File - Jenna Fograscher

advertisement

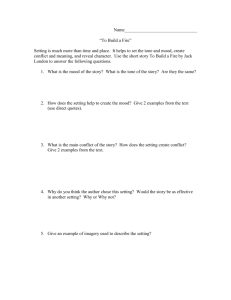

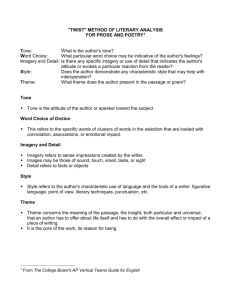

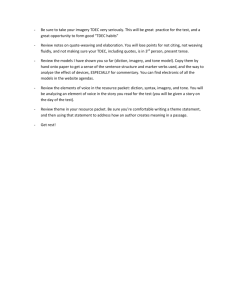

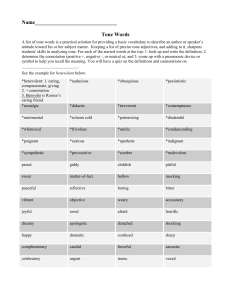

Field Experience #1 Talking About Tone and Punctuating Possession EDT 427 Key Assessment #2: Portfolio A Dr. Romano Assignment: PlanningTeachingAssessing 10/1/2013 Jenna Fograscher Jenna Fograscher, “Imagery and Mood vs. Tone in Macbeth, Act III” Rhetorical Situation: Students are reading Act three of Macbeth and discussing how imagery contributes to the theme of the play. Professional Preparation Skills to be taught: how to identify imagery, how to differentiate between mood and tone Learning Objective/Purpose: Students will learn how to look for imagery in a text, reflect on the mood and tone that it evokes and infer what that means in reference to the overall theme. Common Core ELA Standard-Language-Grade 9-10: RL. 9-10. 1. Cite strong a thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. RL. 9-10. 3. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze it in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details. Logistics of Lesson Academic Language Required: Imagery, mood, tone, theme, motifs Resources and Materials: Text – Simply Shakespeare: Macbeth (pp. 110-153), index cards (1 per student), pens/pencils, teacher-created discussion questions designed to elicit prior knowledge and assess comprehension of the text, teacherdesigned worksheet with graphic organizer for finding examples of imagery, mood and tone. Accommodations for special learners: Visually impaired students will have scenes read to them. Hearing impaired students will have the written text. Inclusion students will have an aide to assist with assignments. Anticipatory Set: Short, humorous story about a time when I, the teacher, woke up to a rainy morning that set the tone for my day. The dark clouds and heavy rain put me in a bad mood and everything else seemed to go wrong throughout the day. My sour mood reflected the tone of the whole day. Instructional Strategies: Before lesson, pass out one index card to each student. On the blank side, have students write their names large enough so I, the teacher, can read them from the front of the class. Aides discussion because I don’t previously know their names. Define imagery and explain example in the play. “But now I am cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in to saucy doubts and fears” (III.iv.26-27). Define mood and discuss its role in the example. Define tone and discuss its role in the example. Discuss how imagery, tone, and mood are displayed in motifs and contribute to theme. While students complete re-reading and worksheet activity, teacher models behavior by doing the task as well (See second attachment). Learning Tasks: Students will listen to teacher explanation and examples. Students will re-read Act III to find examples of imagery. On worksheet, cite one example, describe the mood it evokes, and discuss the tone that the example suggests. Students will share examples with the class and participate in a discussion about how imagery affects mood and tone Informal and Formal Assessment: Teacher observation of students’ performance in class discussion and on worksheet. Teacher assessment of cards written by students in which they use the academic language of the lesson. Explicitly Stated Rule: “Imagery” is figurative or descriptive language in a literary work that paints a picture in the reader’s mind. Imagery is often found in the “motifs” that you’ve discussed in class. Imagery can elicit a “mood,” which is the feelings evoked by reading; how the story, words, imagery affect the reader. “Tone” is what the author is saying about the “theme” through mood. You can use the tone to make inferences and predictions about the story. “Theme” is what Shakespeare wants us to think about, tone is how he wants us to feel about it. He uses imagery and mood to set a tone. Active Practice: Read through Act III of Macbeth and find examples of imagery. Properly cite your example using DIRECT WORDS from the original text. Describe the mood that the image evokes using descriptive words of how you feel and respond to the text. Then describe how the imagery and mood affect the tone of the entire play. Try to think about what the author/playwright (Shakespeare) is trying to express. Quickwrite to assess use of Academic Language: On the back of their index cards, students will have 3 minutes to quickwrite to this prompt: “In paragraph form, tell me the meanings of these words: imagery, tone, mood, theme, and motif. Include how they all connect and contribute to each other. Extension: Continue reading Macbeth, Act IV. Fill out worksheet to cite examples of imagery in the text and describe the mood and tone of each example. They will find one example from each scene. See attachment. Name: ___________________________________ Period: _______ “How does that make you feel?” Directions: Read through Act III of Macbeth and find examples of imagery. Properly cite your example using DIRECT WORDS from the original text. Describe the mood that the image evokes using descriptive words of how you feel and respond to the text. Then describe how the imagery and mood affect the tone of the entire play. Try to think about what the author/playwright (Shakespeare) is trying to express. Example of Imagery Mood: How it makes you feel Tone: What is Shakespeare trying to say? Discussion of how competent students were using academic language The lesson I taught in field experience was on Act III of Macbeth to a tenth grade honors class. My mentor teacher asked me to include a lesson on Imagery and the difference between Mood and Tone. In my observation of previous lessons in the class, I knew that they had prior knowledge about Theme and Motifs, so I decided to connect the new terms I was teaching them to the ideas they already knew. In order to assess the students’ comprehension of the academic language, as well as my efficiency in teaching it, I asked the students to do a quickwrite activity on index cards I provided. I decided to use a model similar to one we did in Dr. Romano’s class because it seemed to be effective in not only measuring our ability to demonstrate understanding, but also the short time frame forced us to make errors in grammar. I told students to write a brief paragraph defining the terms, imagery, mood, tone, theme, and motif, while also explaining how they all connect. I expected the first class I taught to do very well because they seemed to really grasp the concepts during class discussions. Unfortunately, I didn’t get copies of the worksheets they did citing specific examples of imagery and explaining mood and tone, because the teacher kept them for participation grades. I would love to have some quotes from those. But I do have the index cards. What I learned from the quickwrites is that teaching itself is a learning experience. The first class (third period) did not do well at all at explaining what I knew they understood. The majority of the students talked about how the words connected but offered to definition or explanation of what the meant. One example of this was Nathan who said, “These words work together to make up the entire story. Imagery leads to mood. Mood leads to tone. Tone leads to themes and motifs.” I knew Nathan had a firm grasp on the concepts because he either talked or had his hand up for the entire discussion, but his writing doesn’t really demonstrate the meaning of the words or how exactly they connect, though he’s showing that he knows how one term can lead to another. Some of the students gave me appropriate definitions but very vague connections, such as, “They all connect by making the story come alive.” If we were having a conversation in person, I would follow up this statement by asking how the story comes alive, to get them to elaborate on their understanding of the terms. A few students did make me question whether or not they comprehended the language with writing that was just entirely too vague. “The words are all ways to look deeper into a book. They all use our minds to help shape the story.” This student didn’t even include the academic language in his writing. The students who did provide definitions and connections didn’t finish their paragraphs. “Imagery is what image or scene the word put in your head that makes you feel some emotion, which is mood.” Kali clearly comprehends the concepts of the academic language, but didn’t have enough time to finish writing. It was clear that a) I hadn’t given them enough time to complete their quickwrites and b) I had probably used too many words for them to elaborate on academic language. For the second class (sixth period) I decided to change my approach. I told them to only write about imagery, mood, and tone and this time I gave them five minutes. The results were illuminating. This class was much more successful at demonstrating their comprehension of the academic language. Every student wrote accurate definitions of the words, and while some students were able to elaborate on how the words worked together, the main problem with this class was the lack of, or vagueness of, the connections. “Imagery is when authors use very descriptive words to give you a picture in your mind. Mood is the feeling either in the book or what you feel when you read it. Tone is how the author writes that tell you what is about to happen. These all connect because it makes writing better and more interesting.” Evan understands what each of the words means, but is unable to articulate how the terms intertwine. Just like in third period, a few of the students were able to both define and connect the words, but this time they were able to finish. One of the best examples from this class was Erin’s which said, “Imagery is when a piece of writing appears to all your senses. Mood is a big piece in imagery because it adds emotion to what was already appealing to your sense. Tone also shows emotion but you may not agree with it since it is the author’s emotion. When you put your emotions and the author’s tone together with imagery you create a piece.” Erin not only used the academic language, but also connected it to her own reading experience by saying she doesn’t always agree with the tone and explaining why. She does make a word choice mistake by replacing “appeals” with “appears,” but adjusts it in her next sentence. Some of the students in this class used examples from the text to elaborate on comprehension. “Imagery is a way for an author to write that creates an image in the readers head. A way to do this is vividly describe something such as they way Shakespeare described Ducan (Duncan).” And some even make up their own examples! “Imagery is when writer uses words that appeal to the reade. For example the wind blew through like cutting ice.” While there are quite a few formatting mistakes, Emily definitely understood the language and was making her own connections, and she wasn’t the only one. Here is a bar graph illustrating the results of my quickwrite analysis: Since Sixth Period gave me a more accurate and tangible example of the students’ comprehension, I used their quickwrites to decide what concept needed continued or elaborated on in the next lesson. The definitions on “tone” seemed to vary a lot, more than the other words. “Tone is the words and feelings used to create moods.” “Tone is the authors attitude towards whats happening” “Tone is how the writing is described, what mood the writing creates and what mood the author wanted to create.” “Tone is what the author intends you to feel.” One student didn’t even include tone “Tone is the authors opinion towards the subject” “Tone is how the author writes that tell you what is about to happen.” It’s clear that the kids get the gist of what tone is, that the author projects it, but they could probably use more clarification on how we can use it to interpret the text. I think they could also use some more scaffolding in connecting tone to the themes and analyzing what that means in the grand conversation of the text. Jenna Fograscher, “Tone and Theme in Macbeth Act IV, scenes 1-2” Rhetorical Situation: Students are reading Act four of Macbeth and elaborating on tone and discussing what it says about themes in the play. Professional Preparation Skills to be taught: how to identify tone and themes in the play. Learning Objective/Purpose: Students need clarification on the definition and purpose of tone in a text. Common Core ELA Standard-Language-Grade 9-10: RL. 9-10. 1. Cite strong a thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. RL. 9-10. 3. Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze it in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details. Logistics of Lesson Academic Language Required: tone, theme, inferences, predictions, attitude Resources and Materials: Text – Simply Shakespeare: Macbeth (pp. 110-153), teacher-created discussion questions designed to elicit prior knowledge and assess comprehension of the text and academic language, class set of Chrome Books, Padlet.com page made for class Accommodations for special learners: Visually impaired students will have scenes read to them. Hearing impaired students will have the written text. Inclusion students will have an aide to assist with assignments. Anticipatory Set: Students will act out Scene 1 of Act IV. Actors will pay attention to stage directions and the tone of the scene to dictate how they act out the scene. Instructional Strategies: Re-define tone and discuss its role in the play. Teacher will lead a Directed Reading Activity on Act IV, Scenes 1 & 2. Questions about the themes and tones will be concentrated on, while also making predictions based on imagery and tone within the scenes. Lead activity where students post entries on Padlet page describing a theme within Macbeth and how it is reflected in the scenes. Learning Tasks: Students will either act out a scene, or watch their classmates do so. Students will participate in a teacher-led Directed Reading Activity. Students will discuss themes in the appropriate scenes and use their Chrome Books to post reflections on tone on Padlet page. Informal and Formal Assessment: Teacher observation of students’ informal definitions of “tone,” noting whether or not their understanding has improved since last lesson. Teacher observation of student participation in Directed Reading Activity, paying attention to their grasp on themes and how they are affected by tone. Teacher assessment of posts on Padlet. Teacher assessment of shared Google Documents about predictions based on the tone and attitude towards themes. Explicitly Stated Rule: “Tone” is what the author is saying about the “theme” through mood. Gives shape and life to literature; creates and presents the attitude of a work. You can use the tone to make inferences and predictions about the story. “Theme” is what Shakespeare wants us to think about, tone is how he wants us to feel about it. He uses imagery and mood to set a tone. Active Practice: Read through Act IV of Macbeth and find support for themes in the approriate scenes. Properly cite your example using DIRECT WORDS from the original text. Describe the tone of the theme and what that means to the play. Try to think about what the author/playwright (Shakespeare) is trying to express. Quickwrite to assess use of Academic Language: On a Google Document, write a quick prediction for how the events in Scene 1 will play out. Use the tone and attitude towards the themes discussed to support your predictions. Extension: Continue reading Macbeth, Act IV. Pay attention to how well your predictions play out. Conventions With a class of honors students, I wasn’t expecting many technical mistakes. Not only were the kids a little more advanced and experienced, but they were also kind of a bunch of perfectionists (in the best way possible). It turns out I was right, there were not many conventional mistakes made in the writing samples. But because I gave the students a small amount of time to complete it, there were a few errors of neglect because they had to write fast and concentrate on content. The main mistake I found was omitting apostrophes. While only 13 out of 48 students committed the error, there were still patterns displayed that could be addressed in classroom instruction. Students could benefit from a reminder lesson on apostrophes. Most of the mistakes made involved possession. The students included the s at the end of the words to indicate possession, but failed to write the apostrophe. Since this is taught early on, it made me think that they were simply errors of neglect, rather than lack of knowledge. The main words that were misused were “reader’s” and “author’s.” “Imagery is the use of descriptive words to pain a picture is the readers mind…” “The tone is the authors attitude toward what he/she is writing.” “All of these contribute to a pieces genre, atmosphere, and what the reader feels.” While a few students missed the apostrophe in “you’re,” only one of them used the wrong form of the word. “Tone is what the author wants you to picture when your reading his/her writing.” Most students clearly know when to use the apostrophe in a contraction of “you are,” but it can still be a confusing topic and is worth going over. Another contraction apostrophe that multiple students missed is “what’s.” “Imagery paints a picture in your head of whats going on.” “Tone is what the authors trying to say.” In a lesson defining and illustrating the proper use of apostrophe, I could have them not only edit their own mistakes, but create a piece of creative writing in which they demonstrate their new grasp on contractions and possession. Jenna Fograscher, “Apostrophe Use” Rhetorical Situation: Students are displaying pattern of omitting apostrophes in their quickwriting activities. Professional Preparation Skills to be taught: When to use apostrophes in writing. Learning Objective/Purpose: Students will learn the purpose behind apostrophes and practice use in their writing. Common Core ELA Standard-Language-Grade 9-10: L. 9-10. 2. Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English capitalization, punctuation, and spelling when writing. Logistics of Lesson Academic Language Required: Apostrophe, contraction, possession Resources and Materials: two pens/pencils of different colors per student, paper, white board/dry erase markers, teacher-created sentences on white board, index cards containing quickwrites from previous lesson. Accommodations for special learners: Visually impaired students will have scenes read to them. Hearing impaired students will have the written text. Inclusion students will have an aide to assist with assignments. Anticipatory Set: Teacher (me) will address the problem directly. I will find a student that made the mistake and tell about reading his/her quickwrite and how it confused me because I know the student is intelligent and capable of using apostrophes. I will ensure that the student is comfortable enough with me, and the class, to be called out. Make the story humorous and light so that it doesn’t seem accusatory. Illustrate the need to go over the concept of apostrophes again. Instructional Strategies: Definition of contraction, developed through questions posed to the students. Definition of possessions, developed through questions posed to the students. Explain difference between your and you’re. Lead class exercise in punctuation using apostrophes. Learning Tasks: Students will participate in development of definitions of contraction and possession. Selected students will come to white board to punctuate examples of contraction and possession while students in the class think about the process and logic of using apostrophes. They will also answer the teacher’s queries about why they punctuated as they did. Students will re-read their quickwrites Informal and Formal Assessment: Teacher observation of students’ performances at white. Students’ self-monitoring as they complete learning tasks. Teacher observation of students’ use of academic language when defining the uses of apostrophe as a class. Teacher assessment of corrections made on cards written on academic language of previous lesson. Formal assessment later when teacher reads students’ next papers and marks the rubric for correct punctuation of contractions and possession. Explicitly Stated Rule: In your writing, an “apostrophe” must always be used with “contractions” of two words in place of the removed letters. When expressing singular “possession,” an apostrophe is placed before the s. When expressing plural possession, an apostrophe is placed after the s. The contraction of you are is “you’re,” while the possessive form of “your” has no apostrophe. Active Practice (white board): Youre just as pretty as your sister, but shes taller. The funniest poem was Tylers because it was about his dogs cones after they got surgery. Dont forget to bring youre own socks to the bowling alley, those shoes have seen lots of peoples feet. Quickwrite to assess use of Academic Language: Write a brief story in which you use two examples of contraction, two examples of possession, and one example of each version of your/you’re. Extension: Re-read the quickwrite you completed the other day about imagery, mood, and tone in Macbeth. Look for any mistakes in punctuation that you may have made and correct it in a writing utensil of a different color.