Bethany Weeks-JapaneseAlloysReport

advertisement

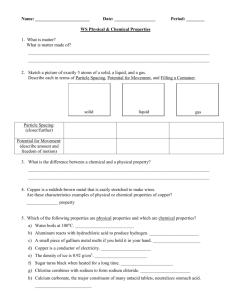

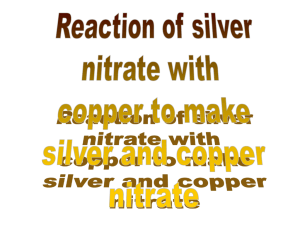

Japanese Non-Ferrous Alloys and their Patination Bethany Weeks Metals are generally considered by the public to have a narrow range of colors but metalsmiths have a long history of trying to counter that view. Different alloys allow for a range of shades between the classic yellow of gold to dark grey of iron. Patination also increases this range of color. The Western approach to metal coloring is a straight on approach, with direct application of metal colorants. In contrast, the Japanese are well-known and respected for their mastery of alloying and patination to color metal without heavy use of external colorants. Two of the most well known Japanese alloys are shibuichi and shakudo, both of which are a copper alloy. Shibuichi (四分一) literally translates as one in four which refers to the amount of silver to copper in the alloy. In actuality, the percentage of silver to copper has a wide range, depending upon the exact shade or coloring desired. In general, shibuichi contains 15– 40% silver but can range as wide as 2-60%. Depending on the amount of silver, or other trace elements, shibuichi can have hues of light to dark grey, brown, blue, and/or green. Higher amounts of silver, creates shiro-shibuichi (白四分一)、literally, white shibuichi and is very pale in grey color. The silver in the alloy creates a eutectic microscructure surrounding the copper dendrites. This not only affects the coloring of the metal but the surface finish, which can be matte with light scattering properties. Different types of this alloy’s crystal growth due to the different quantities of silver can be see below in figure 1. Figure 1. Shibuichi surfaces. The figure on the left shows the crystals on an unfinished piece. The figure on the right is of a piece that has been reduced in thickness by hammering, resulting in distortion in the crystals. You can clearly see the copper (dark) and silver (light) crystals in both. Shakudo (赤銅) is similar to shibuichi except that instead of silver, copper is alloyed with gold. Generally 3-6% gold is used but as much as 10% can be added and have the metal still considered to be shakudo. The coloring of shakudo is generally very dark due to the gold added. The small amount of gold forms into such small particles that they absorb light, creating very dark brown-black metals that look like lacquered wood. Shakudo can have hues of dark red, purple, or brown depending on the amount of gold and trace elements added. Due to this darkening effect by gold, if small amounts are added to shibuichi, it becomes kuro-shibuichi (黒 四分一), which is literally translated as black shibuichi. Some metalsmiths prefer instead to mix shakudo and shibuichi to create kuro-shibuichi and will generally use a range of 60-85% shakudo to 15-40% shibuichi. Due to their ability to create a wide range of colors, shakudo and shibuichi are commonly used in a Japanese metal technique called mokume-gane (木目金). Mokume-gane literally translates to metal wood eye or, slightly less literally, metal wood grains. It is a technique that laminates different metals together into many layers. The layers are then re-exposed by carving and engraving. A good example of a section view of mokume-game can be seen below in Figure 2. Figure 2. Mokume-game used in a tsuba with alternating layers of copper (lighter) and shakudo (darker). Mokume-gane and other uses for shakudo and shibuichi were most commonly used in the making of tsuba (sword guards) after the Meiji era. The Meiji era was a great transition for metallurgy in Japan as it was a time of peace, which forced the tsuba-makers to expand their repertoire. As a result, instead of focusing on basic iron tsuba, they started creating more elaborate ones that included the use of mokume-game with shakudo and shibuichi. They also started making other decorative pieces with the alloys. Figure 3. Tsuba with mokume-game formed to look like cherry blossoms on water Figure 4. Tsuba using shakudo background and gold highlight Figure 5. Shibuichi decorative bowl Figure 6. Shibuichi decorative piece Patination is the other key to creating these metal pieces that have this range of coloring, especially with shibuichi and shakudo. Many of their exotic colorings cannot be obtained without patination. Patination itself is actually a controlled, or uncontrolled, form of oxidation and corrosion of the surface of the metal. It can be highly desired in a piece as a sign of natural aging. However, skilled application of specific recipes can provide a controlled acceleration of this “aging” by oxidizing the surface. There is a wide range of recipes out there to do this. The Japanese use a special patination agent called rokusho. It is widely available inside of Japan but is more rare outside. There are several recipes available for outsiders who wish to make their own rokusho. One such recipes calls for a combination of copper acetate, sodium hydroxide, and calcium carbonate mixed with water. The solution is allowed to separate for a week and is then drained. The remaining formula is rokusho and can be mixed with plum vinegar, or more water, to make the patination solution. Before patination, the metal must be carefully cleaned and prepared. Many Japanese metalsmiths will grate daikon (a type of white Japanese radish) into a paste with 5 parts water and agitate the piece in it as part of their surface preparation. It is unknown exactly what purpose the daikon serves but the metalsmiths believe it helps to prevent tarnish, encourage even coloration, and/or activate the patination solution. When the piece is prepared, the rokusho is mixed with vinegar or water and copper sulfate. The rokusho is brought to a boil and the piece dipped into it. After dipping, the piece is rubbed with diakon paste again and then dipped again. This process is repeated until the desired coloring obtained. Rokusho, particularly makes gold more yellow, silver whiter, copper orange or an orange-red, shakudo blackened, and shibuichi colored grey depending upon the exact alloy and amount of dipping. The Japanese Meiji era was an amazing time for metalsmithing, producing a rainbow of potential colors for metals. Shakudo and shibuichi, in particular, are still being created in Japan as well as abroad by artists and metalsmiths alike due to their beauty and coloration. References Hughes, Richard and Michael Rowe, The Colouring, Bronzing and Patination of Metals. London: Crafts Council. 1982. Kelso, Jim. “Japanese Alloy Basics.” Jim Kelso – Artist/Craftsman. July 25, 2012. <http://jimkelso.com/japanalloys.htm> Nihon Kogeikai. YASUJIMA, Hisashi. Sept 10, 2004. Tokyo National Museum. July 25, 2012. <http://www.nihon-kogeikai.com/TEBIKI-E/4.html> Savage, Elaine and Cyril Stanley Smith. “The Techniques of the Japanese Tsuba-Maker.” Ars Orientalis Vol. 11 (1979), pp.291-328. Shimizu, Yoshiaki. Japan: The Shaping of Daimyo Culture 1185-1868. National Gallery of Art, Washington, New York: George Braziller, Inc. 1988. Smith, Cyril Stanley. “Penrose Memorial Lecture: Metallurgical Footnotes to the History of Art.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Vol. 116, No. 2 (Apr. 17, 1972), pp. 97-135.