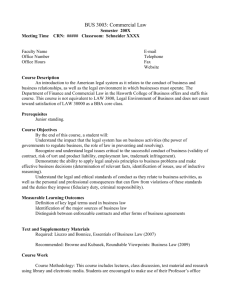

Student Responsibility - MyWeb

advertisement

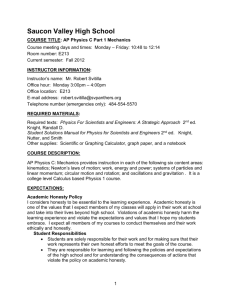

11 April 2011 Operations Management OM 503 PMBA 42 Summer 2011 James P. Gilbert, Ph.D, MBA, CPIM Professor of Operations Management & Quantitative Analysis Crummer Graduate School at Rollins College Operations Leadership: Moving Others to Action Operational Tools, Techniques, and Methods to Insure Delighted Customers and Stakeholders Non-Discrimination Policy Rollins College is committed to equal access and does not discriminate unlawfully against persons with disabilities in its policies, procedures, programs or employment processes. The College recognizes its obligations under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 to provide an environment that does not discriminate against persons with disabilities. If you are a person with a disability on this campus and anticipate needing any type of academic accommodations in order to participate in your classes, please make timely arrangements by disclosing this disability in writing to the Disability Services Office at (box 2613) - Thomas P. Johnson Student Resource Center, 1000 Holt Ave., Winter Park, FL, 37289 or call 407-6462354 for an appointment. 2 Operations Management -- OM 503 Crummer Graduate School at Rollins College James P. Gilbert, Ph.D, MBA, CPIM Professor of Operations Management Office: 205 Crummer Hall Office Phone: 407-628-6375; FAX: 407-646-1550 E-mail: JGILBERT@ROLLINS.EDU Textbook & Cases: Collier, David A. & James R. Evans, OM, 3rd Edition, South-Western CENGAGE Learning: Mason, OH. ISBN-10: 0538479132 ISBN-13: 9780538479134 Cockerell, Lee, Creating Magic: 10 Common Sense Leadership Strategies from a Life at Disney. Cases: National Cranberry Cooperative (Abridged); Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc. (Purchase these two cases at: Course link: http://cb.hbsp.harvard.edu/cb/access/9192278 (NOTE: Over the last several terms only 70% of enrolled students have purchased cases. If you receive a copy of these cases from another student it is stealing. Family Pizza Night at the Bala Bay Inn (file on Black Board). Course Introduction and Objectives Operations management (OM) is defined as the design, operation, and improvement of the systems that create and deliver the firm’s primary products and services. This set of activities relates to the creation and delivery of products and services through the transformation of inputs into outputs. Every aspect of an organization’s management not relating to finance/accounting or marketing is a part of operations management. We see, then, that the vast majority of jobs are in the field of OM. This course deals with strategic and tactical operation decisions, including: product/service design, capacity management, quality management, process design, facility location, layout, supply chain management, human resource development, inventory management, scheduling, and maintenance. Given our location in central Florida, particular emphasis will be placed on service operations management. Background Never before has the field of operations management been as important as right now. Worldwide competitive pressures on manufacturers and service providers continue to heighten. Security concerns post 911 has heightened awareness of the importance of proper inventory management. Customers, rightly so, are more demanding than ever for high quality experiences. In recent years, the manufacturing sector has made great strides to improve its quality, productivity, and cost competitiveness. This said there is still continuous improvement necessary for long-term survival. It is argued that a nation cannot retain its economic superiority without a solid industrial base. Some say that the U.S. is becoming a “hollow” country by purchasing, subcontracting and outsourcing to foreign suppliers. We see at the moment major manufacturers on the edge of failure. The service sector is now going through much of the same pain and gain previously experienced in manufacturing. In the last few years, many service jobs previously filled by U.S. residents are now located in India, Jamaica, Ireland, Mexico and elsewhere around the world. Managing operations is demanding and challenging. Production and service processes are generally very complex. A single company’s operations may involve hundreds of pieces of capital equipment; thousands of people; tens of thousands of materials, components and products; and countless pieces of information. The major challenges are: coordinating all of the elements and getting them to work together as a coherent system, creating those goods and services at low cost and high quality, reducing cycle times and speeding response times. But that’s not all. The environment is constantly changing and the pace is faster—we are in a speedis-everything erea. Operations managers must adapt to be able to accommodate new product and service designs and new processing technologies. Sustainability initiatives are having major impacts on OM. Operations managers are part organizational pilots, part navigators—all on a global scale. To operate globally 3 requires a wide range of talents and skills, the simultaneous mastery of intricate details and broad perspectives. When this is done well, operations management provides organizations and societies major competetive advantages. The most imaginative business plan or most brilliant marketing strategy will flounder without solid operational support. The operations area is the consumer of most of a firm’s capital since materials and labor on average are 60%-80% of the Cost of Goods Sold. Thus, OM is fundamental to financial strategy. Excellence on operations helps to reduce cash flow requirements and variability in cash flows. Variability in cash flows and product delivery can trip up companies that have great product and service offerings. Smart scheduling can be vital to sustained profitability and growth. Savvy operations management is essential for corporate survival in the global marketplace. Course Target This course in the principles of OM presents the best thinking possible on current practice. We will examine business organizations with a large scope. Effective operations management practices work for service providers, manufacturers, profit and not-for-profit businesses, small and large organizations, and government and private sectors. Our OM course is designed to meet the needs of MBA students who are interested in continuing to improve business operating performance for both professional and personal gain. Your contact with operations management may take many forms, including: financial manager, sales/marketing manager, engineer, sourcing manager, customer relations, project manager, strategic planner, services manager, and accounting manager. Given both the broad range of backgrounds and future career paths of course participants, this course concentrates on providing pragmatic concepts, methods and techniques of effective OM. These practical frameworks can be used as reference points to further your understanding of unfamiliar OM situations, and to overcome common misconceptions about the roles and responsibilities of the operations management function. The focus is on what the general manager needs to know to make responsible decisions leading to customer satisfaction, adding economic value, and shareholder wealth. General Course Objectives Participants should understand the principle theories and techniques applicable to current and future operations management roles and responsibilities. The aim here is to expose the graduate student/participant to a wide range of OM situations and to provide a basis on which to assess, evaluate, and recommend specific management actions regarding existing operations. This course provides a foundation in the concepts and analytic methods that are useful in understanding the management of a firm’s operations. The level of analysis varies considerably, from operations strategy to daily control of processes, human resource scheduling, and inventory management. The primary objective of this course is to assist student-participants in building the leadership abilities and skills necessary to participate actively in decision-making involving operations management issues. These skills include the ability to: listen critically, synthesize and analyze relevant information, ethical leadership, and react to and contribute to the discussion on OM directions for the firm. In support of this objective, the course provides: A framework for strategic choices facing the operations function, exposure to the concepts and tradeoffs associated with a firm’s operation, an introduction to basic analytical tools useful in examining operations issues, and an opportunity to gain experience in tackling operations management problems. “You can stare at maps and aerial photos until you eyeballs are coming out. But nothing can take the place of physical reconnaissance. Maps and photos are OK, but seeing the terrain and, if possible, walking over it, is a thousand times better. Learn the terrain. Anonymous drill instructor: Ft. Benning, GA 4 Specific Course Objectives A. Upon completion of the course, participants should have developed an understanding of how different types of operations processes operate in terms of their key characteristics, management tasks, organization, and control. Typical attribute indicators of the intended level of development: 1. The ability to describe in detail the major components of an operations management system. 2. The ability to apply these principles and concepts to any business. B. Upon completion of the course, participants should have acquired a basic set of OM tools and structures for handling five major classes of operating tasks: demand management, materials management (including inventory management and purchasing/supply-chain), quality management, capacity planning and control, and work process scheduling and control. Typical attribute indicators of the intended level of skill acquisition: 1. The ability to design an operating management system for a service or manufacturing business. 2. An awareness of the best practices for problem identification and solution. 3. The ability to constructively criticize inadequate systems and support your position with logic and analysis. C. Upon completion of the course, participants should have acquired the skills necessary to effectively use the techniques of analysis and decision-making that are applicable in such areas as service system development, capacity/facilities planning, process technology management, repetitive production, and others. Typical attribute indicators of the intended level of skill acquisition: 1. The ability to design a basic process control program for a service or manufacturing business. 2. The ability to arrange statistical data into meaningful management information. 3. The ability to support management recommendations with quantitative and qualitative evidence. D. Upon completion of the course, participants should have developed their own framework for relating strategic issues of operations management to other functional areas of the organization. Typical attribute indicators of the intended level of skill development: 1. The ability to explain the roles of engineering, marketing, accounting, finance, and others as related to the operations management system. 2. The ability to justify to management the need for continuous operating improvements. 3. An awareness of the current state of OM worldwide and what might lie ahead. 5 Case Method Instruction or “Participative Education” Purpose of Case Method A case is a description of an actual management situation, commonly involving a decision or problem. Cases allow the student to participate in discussing the analysis and solution of relevant and practical problems. Under the case method of instruction, your professor acts as a guide and not as an oracle. Case method instruction allows for testing of theory-to-practice and places little emphasis on learning by memory. Cases allow the development of proficiency in analyzing management problems reaching decisions as to desirable action, and formulating programs for making effective decisions. Student Responsibility Each case presents specific facts which call for a decision and out of which the student can draw realistic, useful conclusions. For the case method to be successful, each student must come prepared for class because it is the obligation of each individual to make substantive contributions (see section on Participation). Students learn from each other under the guidance of the professor. It is each student’s responsibility to apply the theory learned in the course to the case and develop a reasonable response to the situation. In this way, students must “carry the load” and have the opportunity to advance in the course as fast as the class desires. For guidance on analyzing and presenting a case, see the file: “How to Analyze and Present a Case.doc” (under Course Information on our BlackBoard site). Written and Oral Case Performance Evaluation Criteria I. II. II. IV. V. VI. VII. The student must be able to make the required decisions in the case. The performance objective stressed throughout the course is that the student be able to make concrete decisions and to apply what she/he knows to the concrete situation. A passion for shifting the responsibility in favor of discussion profundities is inadequate performance. The student must demonstrate the ability to think logically, clearly, and self-consistently. A student must show knowledge of what are appropriate facts, assumptions, realities, and the determination of this is case-based and subject matter dependent. The student must be able to present his/her analysis in a cogent and convincing manner. The standard here is the inspirational leader. Effective communication lays out a new order or vision and inspires others to direct their efforts toward that goal by communicating personal conviction and passion for the outcome. The student must have common sense defined as the capability to see the obvious and the relevant. A student should be capable of recognizing and putting appropriate weight on the fundamental issues and factors relevant to the case. The student must demonstrate a willingness and ability to apply analytical muscle and quantitative analysis where relevant. A coherent, self-consistent, relevant argument which ignores the fundamental tools of managerial problem analysis is deficient. The student should be capable of transcending the concrete situation, adding deep perspective, and demonstrating mastery and competence. This is a minimum criterion for an “A” analysis. A student should be able to make use of available data to form a detailed and well-argued specific managerial plan of action, or a detailed and well-argued analysis of situations requested in the case for managerial analysis. While this is similar to some of the previous objectives, it is different in the sense that simply making a decision and arguing for it without filling in the concrete details, the many little decisions which make the main decision meaningful, does not represent a fully successful case analysis. There is a quality of follow-through required for an “A” analysis. 6 Operations Management -- OM 503 Written Case Reports The following guidelines are just those--guidelines. Please show your creativity and ability to convince the reader of your depth of analysis and correctness of your recommendations. The case write-up must be a professional presentation--spelling, punctuation, sentence structure, exhibits, and grammar usage are important to your total message and are evaluated as part of your grade. I will deduct grade points for a non-professional case report. 1. The report should be printed (double spaced, with 1-inch margins and 11-point, Times Roman font. A limit of 5 pages for the body of the report (not including the title page, executive summary, and exhibits) will be enforced. A concise report is important. 2. Start the report with a title page listing all group participants, followed by an executive summary of one page. 3. For the body of the report, no specific format is required; use your best judgment to organize and present convincing arguments. Executive Summary Focused paragraphs summarizing key findings – see BlackBoard discussion of this critical report summary for key executives. Crystal Clear Purpose of Analysis Statement This statement ties together your areas of analysis with making profit. Make a clear chain of events between your analyses and additional profit. Core Problem Statement & Discussion Primary issues, concerns and decisions to be addressed Methodology Methods used to develop analysis Assumptions List assumptions made for your analysis Alternatives Enumerate possible courses of action Analysis Study outcomes of problem-solving alternatives Evaluation Evaluate the alternatives Recommendations Present your recommendations for management with time lines and budget Implementation scheme Specific managerial actions to be taken (and when) Conclusions Discuss the benefits and risks for management if your recommendations are implemented. Make sure you bring out potential profits here. Exhibits Tables and Figures are encouraged as they lead to better understanding for the reader. All must be fully discussed in the body of the report. 4. Avoid a repetition of case facts (assume that we have all read the case). Use case facts only when necessary to support your arguments. 5. Always conclude with specific action items, time lines, costs, and potential new profit. 6. Every exhibit, table or figure used in the report and must be properly cited. All exhibits, tables or figures must be properly titled and labeled. Use text boxes to aid reader understanding of your key points and figures. 7. The report should be convincing, coherent, and unified. This integration process will require coordinating capabilities that are worth the effort. 8. The report should reflect a high degree of professionalism in style and readability. Use a spellchecker and grammar checker. 7 Examinations All examinations are comprehensive for all materials covered up to that point in the course. All course materials are testable. This includes classroom discussions, presentations by the instructor, guest presentations, videos, cases, web plant tours, field experiences, and all other assignments and problems. Participation or (What is Expected of You?) Learning is the Active Pursuit of Knowledge I believe that learning is the active pursuit of knowledge. Our operations management course is designed to enhance the quality of your education. Education is enhanced when the student and instructor enter into a partnership where each actively participates. This course should be dynamic and interactive. All class meetings will involve discussion of topics, problems, and cases. I expect all graduate student participants to show initiative and responsibility sufficient to participate actively in the discussions. You should use your study group as a means of understanding and analyzing problems, case issues, and as a source of data. In my view, learning is most effective when we fully participate in the process of acquiring knowledge. In this course, it is my expectation that everyone actively participate each session. Participation starts with preparation. It is my expectation that each class participant will be fully prepared for each meeting by having read the assigned materials and done other work requested and required. It is extremely important that you prepare for class in advance. I will spend at least 4 hours of preparation time for each hour of class time, and you should do about the same. As a group we will analyze situations, solve problems, build decision models, and address issues relevant to quantitative analysis. Get together and discuss the material before class in your study group. We will talk about recommendations and implementations in a variety of situations. Our classroom should be considered a laboratory in which you can test and improve your ability to convince your peers of the correctness of your approach to complex problems. Effective class participants tend to share the following characteristics: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. The participant is a good listener. Points made are relevant to the discussion and linked to the comments of others. Participants reference other individuals in the class. Comments add to our understanding of the situation or issue. Comments show evidence of forethought and analysis. The participant distinguishes among different kinds of data (that is: facts, opinions, or beliefs). 7. The participant tests new ideas; not all comments are "safe". 8. The participant interacts with other members, not just the instructor. 9. Comments clarify and highlight the important aspects of earlier comments and lead to a clearer statement and understanding of the points being covered. 10. At all times participants are respectful of others. Constructive criticism is critical to effective discussion. Negative personal comments are not tolerated. 8 Classroom Laptop Policy One of the primary reasons that the Crummer Graduate School here at Rollins College has been so successful in the classroom is that each professor strives to develop an environment that actively engages the student in the learning process. This grand oral tradition comes to us from the ancient Greeks and lives today at Rollins College. The primary forms for this learning interchange here at Crummer have been the case method, practical problem use, and dynamic classroom dialogue interchanges. This ability to develop theory through rich discussion and practical experience via problem development and solution has been a highly successful learning model at Rollins College. In the last couple of years, a number of Crummer professors have expressed concerns that some students are not as actively engaged in the discussion as in previous years. The dynamic classroom interchanges that we enjoyed for so many years are becoming less frequent and less challenging (constructive criticism). Tim Lougheed (2002), of the New York Centre for the Support of Teaching, summarizes the issues nicely when he states: “If you don’t have engagement from students, you don’t have attention. . . .If you don’t have attention, you don’t really have learning.” The Internet, Twitter, E-mail, and Instant Messenger are extremely enticing tools that few students are able to overlook for very long when a laptop computer and internet connection are available to them in the classroom. For many students, instant messaging in various forms has become like the telephone. When the phone rings, we have a strong desire to answer it regardless of what is taking place in our lives at that moment. When students are viewing the Internet they are disrupting their personal learning opportunity and those of the students around them. With incoming messages popping up on neighboring screens and colleagues responding to non-class related information, all students lose in the process. This disruption in concentration also includes active image screen savers the cause the eye to move to the computer screen. In the college classroom, all of the class is hurt directly when one or more individual members elect to drop out of the learning experience and involve themselves in inappropriate use of the computer. The grading scheme for our course requires daily active participation by all students. Your participation grade will be reduced for inappropriate use of the computer in our class. You should not be viewing internet material unless specifically requested by the professor. 9 Classroom Laptop Policy: Student Responsibilities You are responsible for bringing your laptop to class on days we are scheduled to use it. Your laptop should be in good working condition. If you are experiencing problems with your machine it is your responsibility to visit the Information Technology specialists for assistance before class begins. If your laptop is missing or stolen, you need to report the situation immediately to Campus Safety. It is your responsibility to obtain a loaner laptop before the start of class. During classroom discussions, you should not be engaged on the network unless specifically instructed to do so. [To do so invites many distractions—web surfing, email, chats, social networking, and the like. These activities are no more acceptable than talking on a cell phone or inappropriate discussions with your neighbor during class time.] During quizzes and examinations, you may by viewing online material only at the instruction of the professor. During quizzes and examinations, the only items that should be open on your computer are those directly related to the specific needs of the situation as directed by your instructor or proctor. Always set up your laptop computer before the start of class. Boot up and program start up may take a few minutes, so please start preparing as soon as you enter the classroom. Setting up after the start of class is disruptive and discourteous. Please make sure the batteries of your laptop and any needed peripherals are fully charged before class begins (our classrooms have individual power outlets but it is a good idea as power failures do occur). You may use your laptop to take class notes. You are responsible for checking your Rollins e-mail and course Blackboard site at least once each day for class assignments and announcements. You are responsible for downloading all information, assignments, and files from your professor before the start of class. Keep the Microsoft Operating System and Microsoft Office software on your laptop at all times. IMPORTANT: Always store backup copies of your critical class materials. Never store your only copy of a case, paper, class notes, or problem solution on the net in case the server is down and you are unable to access the file in a timely manner. 10 Grade Determination “Learning is complete only when the learner has internalized the concepts and can apply it to a situation.” Grades are reported as follows: A Indicates consistently excellent work B Indicates work of the quality normally expected of a graduate student C Indicates work that is below the quality expected in graduate study F Indicates work that is unacceptable in the graduate level of study I Incomplete indicates that the student and instructor have agreed that outstanding work will be completed and the grade changed to A, B, C or F by the mid-term point of the following term W Withdrawal X Nonattendance N Audit NOTE: An “A” Grade may be modified by a minus as appropriate, while grades of B and C may be modified by a plus or minus as appropriate. Grades in this course are based on both individual and group work. Graded assignments are intended to assess your understanding of the general and specific objectives listed for this course. Your depth of understanding will be assessed using the typical attribute indicators presented in this syllabus, active participation via case method instruction, examination evaluations, and other methods as presented in this document. Please note that class absences do affect your participation score. Your final grade will be determined from the following weighting scheme: Opportunities: Actively Engaged Class Participation (See Participation or (What is Expected of You?) and In-class Computer Use) Case Presentations1, Class Assignments & Quizzes Examinations (Mid-term 25% & Final 25%) 5% 45% 50% Individual and Group case presentations are graded on content, professionalism, power to convince audience of your views, and performance (see Written and Oral Case Performance Evaluation Criteria in this document for details). Individual performance in team activities will be evaluated and weak contributions will affect your course grade. All materials to be handed-in to your instructor are due and available at the start of class. Your grade will reflect a deduction for all work turned in after the start of class (or when called for by your instructor after that time) for any reason. Grading Scheme A AB+ B B- 93 to 100% 90 to 92% 87 to 89% 83 to 86% 80 to 82% C+ C CF 77 to 79% 73 to 76% 70 to 72% Below 70% There are 2 major cases in the course: National Cranberry Cooperative & Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A. These cases are weighed more heavily than the shorter cases. 1 11 Crummer Graduate School MBA Student Code of Academic Honesty2 A primary goal of the MBA students at the Crummer Graduate School of Business is to obtain a high quality graduate education that includes important managerial skills, intellectual achievement, personal development, social responsibility, and high ethical and moral standards. Students recognize that the value of their degree depends on the quality of the academic program, on the quality of faculty and fellow students, on the fairness of their grades, and on a learning environment in which high standards of ethics and honesty prevail. For an academic community to thrive in an environment of learning and free exchange of ideas, ethical conduct is inseparable from wisdom. Faculty and students affirm the value of academic honesty and accept the responsibility to maintain an environment in which academic dishonesty of any type is not tolerated. Students at the Crummer Graduate School of Business subscribe to a code of academic honesty and affirm that they will not participate in plagiarism, cheating, violation of test policies, or complicity in dishonest behavior, nor will they tolerate in their midst students who violate this code. As a reminder of this affirmation, students signed a statement indicating that the work presented for classes is their own and that they have neither received nor given any help or information during examinations. Policy The faculty of the Crummer Graduate School of Business considers academic dishonesty as a serious breach of academic ethics that cannot be tolerated in an environment of learning and free exchange of ideas. It is therefore the policy of the Crummer Graduate School that a student who commits an act of academic dishonesty shall receive the grade of “F” in the course in which the conduct occurred. A greater penalty, including dismissal from the program, may be imposed especially in cases of repeat offenses during a student’s program of study. Academic dishonesty is defined as representing another's work as one's own, active complicity in such falsification, or violation of test policies. In order to ensure an environment and atmosphere that encourages academic honesty, the following policy is established. 1. The faculty in cooperation with the MBA Associations of the four programs shall establish and maintain a Student Code of Academic Honesty. A written copy of the code and the School's policy on academic honesty shall be provided to each student entering the School's programs. 2. Each instructor is responsible for explaining to his or her students what constitutes academic honesty within the context of a particular course. Additionally, each syllabus should include a section describing the requirements set by that instructor for that course. 3. The Crummer Graduate School shall appoint an Academic Discipline Committee whose function shall be to investigate infractions of academic honesty. This committee will be made up of seven members: three faculty members, selected by the Dean, one of whom shall serve as chair, and four student members, one from each of the four programs. Each student member will typically be the class president/spokesperson of their class but may be selected by election if the class so desires. In the event of a suspected infraction, the instructor of the course in which the alleged infraction occurred shall inform both the student and the chairperson of the Academic Discipline Committee as expeditiously as possible and shall provide whatever evidence is available to the Committee. 4. The Academic Discipline Committee shall review each case and make recommendations to the faculty. The responsibility for deciding on an appropriate penalty rests with the faculty of the School as a whole. Individual instructors shall not be responsible for administering punishment for academic dishonesty. 5. The student shall have the right to appeal the decision of the faculty to the Dean of the Crummer Graduate School. The Dean's decision on the appeal shall be final. 2 This page will be superseded by any revision approved by the faculty of the Crummer Graduate School. 12 Academic Honesty: OM 503 According to the Crummer Graduate School Policy on Academic Honesty, it is the responsibility of each faculty member to explain to students what constitutes academic honesty within the context of a particular course. The following comments apply to OM 503, Operations Management: 1. Case assignments, when handed in, are to be the work of those individuals placing their names on the paper or computer file. When group assignments are made, it is anticipated that all students in the group will make substantial contributions to the work of the group. While the contributions of an individual will vary from one assignment to another because of abilities and schedules, it is viewed as dishonest for a student’s name to appear on case assignments when that student has not established a record of making substantial contributions to the group effort. 2. Academic honesty does not permit students who have not submitted a case report to look at cases submitted in current or prior terms by other students in this class or any other class. 3. Academic honesty in this course prohibits students from talking with others who have already participated in a class discussion of a case (or problem) if the intent of the discussion is to gain insight into analysis of the case (or problem). However, it is beneficial (and quite honest) to ask other students about methods and procedures, if the intent of the discussion is to learn about those methods and procedures rather than their specific application to a case. To summarize, ask questions and discuss freely when the intent is a better understanding of the material in the course. Do not discuss when the intent is to gain competitive grade advantage about a particular case. 4. My practice is to encourage course participants to keep possession of a copy3 of the case analysis reports during the class discussion, so that a student may refer to the report during the discussion. 5. Academic honesty does not allow students to give or receive information about specific questions on an examination that is still active. Scheduling sometimes requires that students will take examinations at different times; all students are expected to respect the necessity that these scheduling requirements will not be used to permit information about the examination to flow from one student to other students who have not yet taken the exam, whether those students are in the same section of the course or different sections of the same course within an academic term. 3 NOTE: All assignments to be turned in are due at the start of class. Grades may be lowered for late assignments. 13 Dress Code Guidelines Crummer students with support of the faculty created these guidelines to preserve the ideals of professionalism and excellence that are represented in the Crummer Community. Absolutes Other than for religious or health reasons, no hats should be worn inside the Crummer building. No “flip-flops” or casual shoes should be worn at any time. No sweat shirts, cut-offs, midriff, or strapless tops. No jeans or denim pants. Business Casual Dress – Required for Classroom Attendance, Orientation, Guest speakers in class, the Dean’s Lunches. Examples for Men – Khakis, chinos, corduroys or other nondenim slacks (no jeans or shorts) Polo, collared shirt or dress shirt (jacket or blazer is optional and a tie is not required) Dress shoes or loafers Examples for Women – Khaki or dark colored pants, appropriate length skirts or dresses (no jeans or shorts) Blouses, polo and button-up shirts (jacket or blazer is optional) Dress shoes (shoes that are comfortable and appropriate for your outfit). Professional Dress – Required for all class presentations, networking events, interviews, and the Dean’s Leadership Lecture Series. Examples for Men – Jacket and dress pants in dark colors (black, navy, or charcoal grey) Dress shirt preferably in white or blue Conservative tie (basic colors and patterns) Dress shoes with high-fitting dark socks Simple and essential-only jewelry Light on the cologne or aftershave Examples for Women – Skirt or pant suit in dark colors (black, navy, or charcoal grey) Dress shirt or shell Sensible heel pumps Stockings Simple and essential-only jewelry Light on perfume Approved 12 April 2010