imperialism in china: summaries of key events

advertisement

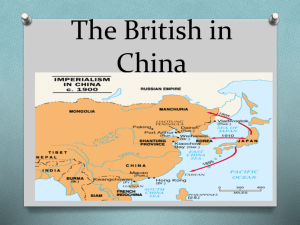

IMPERIALISM IN CHINA: SUMMARIES OF KEY EVENTS READ: The actions that Europe and later America took against the Chinese illustrate the depths to which the Great Powers would sink in order expand their power and profits. The Japanese were also involved in the weakening and denigration of the Chinese, who were subjected to more injustices before becoming communist in the 1940s. Part I. Directions: Read the following summary. Make notes in the margins or outline it. The Opium War and Foreign Encroachment Two things happened in the eighteenth century that made it difficult for England to balance its trade with the East. First, the British became a nation of tea drinkers and the demand for Chinese tea rose astronomically. It is estimated that the average London worker spent five percent of his or her total household budget on tea. Second, northern Chinese merchants began to ship Chinese cotton from the interior to the south to compete with the Indian cotton that Britain had used to help pay for its tea consumption habits. To prevent a trade imbalance, the British tried to sell more of their own products to China, but there was not much demand for heavy woolen fabrics in a country accustomed to either cotton padding or silk. The only solution was to increase the amount of Indian goods to pay for these Chinese luxuries, and increasingly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the item provided to China was Bengal opium. With greater opium supplies had naturally come an increase in demand and usage throughout the country, in spite of repeated prohibitions by the Chinese government and officials. The British did all they could to increase the trade: They bribed officials, helped the Chinese work out elaborate smuggling schemes to get the opium into China's interior, and distributed free samples of the drug to innocent victims. The cost to China was enormous. The drug weakened a large percentage of the population (some estimate that 10 percent of the population regularly used opium by the late nineteenth century), and silver began to flow out of the country to pay for the opium. Many of the economic problems China faced later were either directly or indirectly traced to the opium trade. The government debated about whether to legalize the drug through a government monopoly like that on salt, hoping to barter Chinese goods in return for opium. But since the Chinese were fully aware of the harms of addiction, in 1838 the emperor decided to send one of his most able officials, Lin Tse-hsu, to Canton to do whatever necessary to end the traffic forever. Lin was able to put his first two proposals into effect easily. Addicts were rounded up, forcibly treated, and taken off the habit, and domestic drug dealers were harshly punished. His third objective--to confiscate foreign stores and force foreign merchants to sign pledges of good conduct, agreeing never to trade in opium and to be punished by Chinese law if ever found in violation--eventually brought war. Opinion in England was divided: Some British did indeed feel morally uneasy about the trade, but they were overruled by those who wanted to increase England's China trade and teach the arrogant Chinese a good lesson. Western military weapons, including percussion lock muskets, heavy artillery, and paddlewheel gunboats, were far superior to China's. Britain's troops had recently been toughened in the Napoleonic wars, and Britain could muster garrisons, warships, and provisions from its nearby colonies in Southeast Asia and India. The result was a disaster for the Chinese. By the summer of 1842 British ships were victorious and were even preparing to shell the old capital, Nanking, in central China. The emperor therefore had no choice but to accept the British demands and sign a peace agreement. This agreement, the first of the "unequal treaties," opened China to the West and marked the beginning of western exploitation of the nation. Other humiliating defeats followed in what one historian has called China's "treaty century" (major aspects of the so-called "unequal treaties" were not formally voided until 1943). In 1843, France and the U.S., and Russia in 1858, negotiated treaties similar to England's Nanking (Nanjing) Treaty, including a provision for extraterritoriality, whereby foreign nationals in China were immune from Chinese law. To compel a reluctant China to shift from its traditional tribute based foreign relations to treaty relations, Europeans fought a second war with China from 18581860, and the concluding Treaty of Tientsin (Tianjin) and Convention of Peking (Beijing) increased China's semi-colonial status. More ports were open to foreign residence and trade, and foreigners, especially missionaries, were allowed free movement and business anywhere in the country. Conflicts for the rest of the century wrung more humiliating concessions from China: with Russia over claims in China's far west and northeast in 1850 and 1860, with England over access to the upper reaches of the Yangtze River in 1876, with France over northern Vietnam in 1884, with Japan over its claims to Korea and northeast China in 1895, and with many foreign powers after 1897 which demanded "spheres of influence," especially for constructing railroads and mines. In 1900, an international army suppressed the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion in northern China, destroying much of Beijing in the process. Each of these defeats brought more foreign demands, greater indemnities that China had to repay, more foreign presence along the coast, and more foreign participation in China's political and economic life. Little wonder that many in China were worried by the century's end that China was being sliced up "like a melon. Changing China: Readings in the History of China from the Opium War to the Present, edited by J. Mason Gentzler. 1977 by Praeger Publishers, A Division of Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Part II. Read the following summaries and documents. For the summaries, make notes in the margins or outline each one. For the primary sources, make sure you are able to interpret their meanings and significances as they relate to the key events described in the summaries. The Taiping Rebellion (1850 - 64) The Taiping Rebellion (1850 - 64) was by far the bloodiest war of the nineteenth century. The revolt was a radical political and religious uprising,that ravaged 17 Chinese provinces and cost 20 million lives. The rebels rose against the tyranny of the Manchus, supporting a program partly based on Christian doctrines. Among their aims were public ownership of land and the establishment of a self-reliant economy. Their slogans - to share property in common - attracted many famine-stricken peasants, and the Taiping ranks swelled to more than one million soldiers. Under the leadership of Hung Hsiu-chuan they captured Nanking and made it their capital. Hung founded the 'Great Peaceful Heavenly Dynasty' in 1851. After a few years the leaders began to quarrel among themselves, the reforms were not completed and their opponents, supported by the Western powers, defeated the Taiping in 1864. But the Manchu government was so weakened by the rebellion that it never again was able to effectively rule China. The Boxer Rebellion (1900) The Boxer Rebellion was a peasant uprising that attempted to drive all foreigners from China and to destroy the Mongol Ch'ing dynasty. The Boxers were a secret society known as the I-ho ch'uan (Righteous and Harmonious Fists). Its members practiced certain boxing rituals in the belief that this gave them supernatural powers and made them invulnerable to bullets. After Japan defeated China in 1895, Japan and the Western Powers began to control more and more of the Chinese economy. In reaction the Boxer movement attracted popular support. As early as 1899, Boxers were killing Chinese Christians. In 1900 the Dowager Empress persuaded the Boxers to drop their opposition to the Ch'ing dynasty and unite with it to destroy the foreigners. All over northern China Missionaries and other foreigners were killed, and in Peking the Boxer besieged foreign diplomats who took refuge in the foreign legations. In 1900 an international force landed at Tientsin and fought its way to Peking. In August the siege was raised, the city looted, and the imperial palaces were sacked. The court fled to Sian, and representatives of the Dowager Empress had to sue for peace. The terms of the agreement signed in 1901 were the harshest imposed on China by Western powers. Source: World History (textbook from Glencoe) Conditions of the Treaty of Nanking I.-Lasting peace between the two nations. II.-The ports of Canton, Amoy, Fuchau, Ningpo, and Shangai to be opened to British trade and residence, and trade conducted according to a well-understood tariff. III.-It being obviously necessary and desirable that British subjects should have some port whereat they may careen and refit their ships when required,î the island of Hong Kong to be ceded to her Majesty. IV.-Six millions of dollars to be paid as the value of the opium which was delivered up as ransom for the lives of H.N.M. Superintendent and subjects,î in March, 1839. V.-Three millions of dollars to be paid for the debts due to British merchants. VI.-Twelve millions to be paid for the expenses incurred in the expedition sent out to obtain redress for the violent and unjust proceedings of the Chinese high authorities. VII.-The entire amount of $21,000,000 to be paid before December 31, 1845. VIII.-All prisoners of war to be immediately released by the Chinese. IX.-The Emperor to grant full and entire amnesty to those of his subjects who had aided the British. X.-A regular and fair tariff of export and import custom and other dues to be established at the open ports, and a transit duty to be levied in addition which will give goods a free conveyance to all places in China. XI.-Official correspondence to be hereafter conducted on terms of equality according to the payments of money. XII.-Conditions for restoring the places held by British troops to be according to the payments of money. XIII.-Time of exchanging ratifications and carrying the treaty into effect. (Williams, 197-198) Chinese Response to the treaty: [Tappan Introduction]: “From a paper that was agreed to at a great public meeting in Canton. Behold that vile English nation! Its ruler is at one time a woman, then a man, and then perhaps a woman again; its people are at one time like vultures, and then they are like wild beasts, with dispositions more fierce and furious than the tiger or wolf, and natures more greedy than anacondas or swine. These people having long steadily devoured all the western barbarians, and like demons of the night, they now suddenly exalt themselves here. During the reigns of the emperors Kien-lung and Kia-king these English barbarians humbly besought an entrance and permission to deliver tribute and presents; they afterwards presumptuously asked to have Chu-san; but our sovereigns, clearly perceiving their traitorous designs, gave them a determined refusal. From that time, linking themselves with traitorous Chinese traders, they have carried on a large trade and poisoned our brave people with opium. Verily, the English barbarians murder all of us that they can. They are dogs, whose desires can never be satisfied. Therefore we need not inquire whether the peace they have now made be real or pretended. Let us all rise, arm, unite, and go against them. We do here bind ourselves to vengeance, and express these our sincere intentions in order to exhibit our high principles and patriotism. The gods from on high now look down upon us; let us not lose our just and firm resolution.” Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., China, Japan, and the Islands of the Pacific, Vol. I of The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song, and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), p. 197