File - MYP World History

advertisement

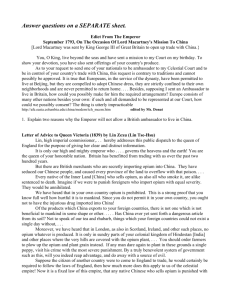

BL- THE OPIUM WARS (1839-42 & 1856-60) Two trading wars in the mid-19th century in which Western nations gained commercial privileges in China. The first Opium War (1839-42) was between China and Britain, and the second Opium War (1856-60), also known as the "Arrow" War, or the Anglo-French War in China, was fought by Britain and France against China. The Opium Wars arose from China's attempts to suppress the opium trade. British traders had been illegally exporting opium to China, and the resulting widespread addiction was causing serious social and economic disruption in the country. In 1839 the Chinese government confiscated all opium warehoused at Canton by British merchants. The antagonism between the two sides increased a few days later when some drunken British sailors killed a Chinese villager. The British government, which did not trust the Chinese legal system, refused to turn the accused men over to the Chinese courts. Hostilities broke out, and the small British forces were quickly victorious. The Treaty of Nanking, signed Aug. 29, 1842, and the British Supplementary Treaty of the Bogue, signed Oct. 8, 1843, provided for the payment of a large indemnity by China, cession of five ports for British trade and residence, and the right of British citizens to be tried by British courts. Other Western countries quickly demanded and were given similar privileges. In 1856 the British, seeking to extend their trading rights in China, found an excuse to renew hostilities when some Chinese officials boarded the ship Arrow and lowered the British flag. The French joined the British in this war, using as their excuse the murder of a French missionary in the interior of China. The allies began military operations in late 1857 and quickly forced the Chinese to sign the treaties of Tientsin (1858), which provided residence in Peking for foreign envoys, the opening of several new ports to Western trade and residence, the right of foreign travel in the interior of China, and freedom of movement for Christian missionaries. In further negotiations in Shanghai later in the year, the importation of opium was legalized. The Chinese, however, refused to ratify the treaties, and the allies resumed hostilities, captured Peking, and burned the emperor's summer palace. In 1860 the Chinese signed the Peking Convention, in which they agreed to observe the treaties of Tientsin. (Encyclopaedia Britannica Article) SL: Opium Wars Introduction Opium Wars (1839-1842, 1856-1860), two conflicts between Britain and China over trading rights. In the Second Opium War, also known as the Arrow War or the Anglo-French War in China , French forces joined the British. The wars are so named because they centered on the trade of opium, a powerful narcotic that British merchants were smuggling into China in vast quantities. The Chinese lost both wars. As a result, they found themselves forced into the emerging world of global trade and diplomacy, while Western nations gained significant commercial privileges and territory in China . British-Chinese Trade Although the Qing dynasty that had ruled China since the mid-17th century was often depicted as isolationist, the Qing emperors in fact hoped to limit and control foreign trade, not to eliminate it.This was the object of the so-called Canton system of trade, which in 1757 established the southern city of Guangzhou ( Canton ) as the sole legal port for foreign trade with China . This trade was heavily regulated by the cohong, a group of Chinese merchants who paid the emperor handsomely for their monopoly power. The cohong set prices, collected duties, and levied numerous fees on foreign merchants, who were forbidden to interact with the Chinese people or even to learn Chinese. Some merchants chafed under such restrictions, especially since they were forbidden to lodge complaints directly with Chinese officials. Still, European traders were accustomed to monopolies; most European trade with Asia was carried out by the English, Dutch, and French East India Companies, merchant groups that had purchased monopoly trading privileges from the governments of their countries much as the cohong had. The real irritant in Chinese-British relations, however, came to be the unequal balance of trade between the two countries. The principal item of exchange was Chinese tea, which had become the British national drink over the course of the 18th century. By the early 19th century, British ships were transporting millions of kilograms of tea back to England every year. Unfortunately, English merchants were unable to come up with products to sell to the Chinese in similar volume, and in some years, 90 percent of the cargo brought by British ships to China consisted of silver bullion. The British viewed such an imbalance as unhealthy and as early as 1793 organized a diplomatic mission to China to demand that the Canton system be abandoned and all of China opened to British trade. The Chinese leaders refused to comply. In his famous reply to King George III, Emperor Qianlong declared, "We possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country's manufactures." The Opium Trade Opium became the tool by which the British traders eventually broke open the Chinese market. The Chinese had long known the addictive drug—recreational use among the leisured classes had prompted a ban on the sale and smoking of opium as early as 1729. In 1773 the English East India Company (EEIC) established a monopoly over opium cultivation in India . They marketed the drug in China through Western merchants who were licensed by but not technically members of the EEIC, which had a monopoly on trade in China . The importation and cultivation of opium were outlawed in China in 1796, reflecting the inroads that Indian opium had made there, but the ban was ineffective. In 1819 greater domestic competition within India lowered opium prices dramatically, causing Chinese consumption to shoot up accordingly. Domestic political developments in Britain led to the breakup of the EEIC monopoly in 1833, allowing new groups of merchants to enter the Chinese market. The following year, British exports to China rose to new heights. The volume of this trade reversed the direction of the flow of silver, and China paid out 34 million Mexican silver dollars (the common international currency of the day) to purchase opium in the 1830s. Although the idle rich were the majority of the Chinese addicts, many poor Chinese became addicted as well, and all suffered from the economic effects of the loss of silver. The First Opium War The breakup of the EEIC monopoly was the immediate cause of the First Opium War, both because it led to a huge increase in opium traffic and because, without the EEIC to serve as a buffer, the British government now found itself obliged to intervene more frequently in China. A vocal part of the English public clamored for greater access to China 's huge market, and Britain often sought these goals through bluster and the threat of force. China saw the problem differently and moved to stem the trade imbalance and the opium craze that plagued its people. In late 1838 Emperor Qianlong appointed a famed official, Lin Zexu, as imperial commissioner and sent him to Guangzhou to solve the problem. In March 1839 Lin ordered the British merchants to hand over all of their opium stocks within three days and to sign a bond pledging never again to traffic in the drug under penalty of death. When British superintendent of trade Charles Elliot attempted to negotiate, Lin suspended trade and held all foreign merchants hostage. Elliot then ordered the merchants to hand over their opium to him, after which he surrendered it to Lin. Lin washed some 9 million Mexican silver dollars worth of opium into the sea, not realizing that English patriots would view this as destruction of Crown property. While Lin and the British merchants jousted over the signing of the bonds, officials in England dispatched an armed force to China . The Chinese had prepared for war at Guangzhou , but the British force simply blockaded that city on its way north toward the capital of Beijing , where officials met with the Chinese. The result of subsequent negotiations was the Convention of Quanbi in January 1841, in which the bare minimum of British demands were met. The agreement was subsequently rejected by both sides: The emperor was enraged that his representative had made real concessions, while the British felt that Elliot had failed to press his advantage. Sir Henry Pottinger replaced Elliot in August 1841 and immediately directed his forces to occupy important cities along the coast, including Ningbo and Tianjin . In the spring of 1842 the English renewed their offensive, triumphing readily over valiant but underarmed Chinese resistance. By late June the British occupied Zhenjiang , an important communication center and entry to theGrand Canal , the artery by which rice from the southern regions reached the northern capital. The Chinese agreed to negotiate, and at gunpoint they signed the Treaty of Nanjing ( Nanking ) onAugust 29, 1842 . The treaty more than fulfilled England 's original goals: The cohong was abolished, four more Chinese ports were opened to trade ( Fuzhou , Ningbo , Shanghai , and Xiamen ),and the island of Hong Kong was ceded to the British. Opium Wars Higher Level The British were keen to have the Chinese smoke opium because it provided them with a huge profit. They completely ignored the sanctions against it by the Chinese government and the pleas from China to stop the exportation of opium from India to China. In the early 1800’s, domestic competition within India caused the price of opium to decrease. As a result, the demand for opium in China spiked. Domestic problems in India further affected the opium trade in 1833 by ending the British East India Company’s monopoly. Depiction of a Chinese opium den In 1834 England sent Lord Napier to Macao to discuss trade with government officials. He wanted to negotiate the terms of the Canton system now that the East India Company no longer had a monopoly. However, the Canton system did not allow direct contact with Chinese officials and Napier was turned away by the governor. The governor closed trade on September 2nd and the British, despite Lord Napier’s desire to force open the port, agreed to continue trading under the old terms. Without the British East India Company to serve as a buffer, the British government had to intervene more frequently in China. This angered the Chinese government and further stressed relations. In March of 1839 the emperor appointed Lin Zexu as an official to govern trade in Canton. Lin sought to enforce the emperor’s ban on opium and demanded that the British merchants hand over opium stock within three days and sign a bond promising to not traffic opium. The penalty for breaking this agreement would be death. Charles Elliot, the British superintendent of trade, tried to negotiate with Lin but failed. In response, Lin suspended trade and held all foreign merchants hostage. Elliot surrendered to Lin and ordered the merchants to relinquish their opium. Lin disposed of the opium by dumping it into the sea. The Chinese government did not realize the message this would send, as the British saw it as the destruction of their private property. China and Britain were now set up for a major conflict the British government was extremely insulted by Lin’s destruction of the opium, and took it as a sign of hostility. Lin sent a letter to Queen Victoria trying to resolve the matter, letting the British know that if they objected to the death penalty that would be imposed on those involved in the opium trade they could sign a different document that would allow them to trade freely at the mouth of the Bogue, heavily supervised by the Chuenpo Fort. The British refused the offer and sent warships and soldiers. The forces arrived in June of 1840 and started to attack coastal villages. Opium Wars During this period the British navy was the most formidable fighting force. The Qing armies fought back valiantly, but they were not as well equipped or organized. The British had muskets and cannons, as well as extensive formal training. Lin tried to overcome China’s military problem by “arming the people”. He raised militia levies so each Cantonese village could have its own militia. He also recruited unemployed tea porters, having the Hong pay them $6 a month to be soldiers. He also paid fishermen $6 a month to patrol and raid on their boats. He offered money to those that killed members of the British military or sank ships. Lin also tried to copy Western techniques by shipping in 200 cannons to Canton and purchasing a 1,080 ton ship to reinforce the blockade there.The British troops took Canton and sailed up the Yangtze river, destroying tax barges on the way. This significantly cut the revenues of the imperial court in Beijing. In January of 1841 Charles Elliot arrived in Beijing to negotiate with the Chinese in the Convention of Quabi. The Chinese met the minimum demands of the British, but neither side accepted the agreement. The Chinese emperor was indignant that his official had given anything to the British, and the British government wanted more. British occupation of ports allowed for opium trade to re-open. Opium ships would follow the British fleet into ports in order to set up trade. The merchants made no attempt to hide while smuggling the drug ashore and the prices of opium were openly published. In August of 1841 Sir Henry Pottinger replaces Charles Elliot as superintendent of trade. He orders British forces to occupy cities along the coast and in the Spring of 1842 the British fully resume their offensive position. They traveled north and took Amoy, Ting-hai, and Ning-po. In May reinforcements from India arrived and Wu-sung, Shanghai, and Zhenjiang were taken. Zhenjiang was a very important communication center and was also the entry to the Grand Canal. The British blocked the Grand Canal, preventing rice and other goods from the southern regions of China from reaching to the northern capital. After these events, the Chinese agreed to negotiate. They met with the British in August of 1842, and in the 29th the Treaty of Nanking was agreed upon. The treaty decidedly favored the British- the Hong were abolished, the ports of Fuzhou, Ningbo, Shanghai, and Xiamen were opened to trade, the Chinese had to pay an indemnity of $21,000,000, and Hong Kong was ceded to the British.