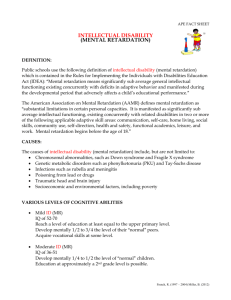

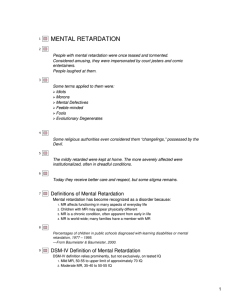

STR -Mental Retardation FINALLLL

advertisement