THE EFFECT OF

PERFORMANCEAND

RELATIONSHIP

JOB SATISFACTION ON JOB

ORGANIZATIONAL OBLIGATION

Fakhraddin Maroofi, department of management University of Kurdistan Sanandaj, Iran

Corresponding author Email: maroofif2900@gmail.com

Marzieh Dehghani, Department of management, science and research branch, Islamic Azad University,

Sanandaj, Iran

Email: sima67_2012@yahoo.com

Abstract

This research tested the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. As a result the

research concluded the effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. A self-manage questionnaire was occupied and allocated among senior and middle management

staff of manufacturing sector in electrical and electronic companies in Iran. Five hindered and eighty four

samples were randomly selected in the research. The obtained data were analyzed based on the descriptive and

conclusive statistics using SPSS. The results showed that there was as a positive relationship between

organizational obligation and job performance. The hierarchical analysis discovered that job satisfaction played

moderating role on the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance.

Keywords: Organizational obligation, job performance, job satisfaction, Iran

1. Introduction

According to Steinhaus & Perry (1996) obligated and satisfied workers are improbably to show low

performance and are usually highly productive who relate to organizational targets and organizational values

(Churchill et al., (1993). The popularity of work attitudes concepts arise from its linkage with several workers’

work behaviors. Robbins, (2005) and Lancaster and Jobber, (1994) suggested that job satisfaction can had an

effect on several work related results like job performance (Robbins, 2005 and Lancaster and Jobber, 1994);

absenteeism (Lawson and Fukami, 1984) and voluntary turnover (Hom and Griffeth, 1995). Although

previous research emphasis on the behavioral work results of turnover and absenteeism, it has however been

identified that employee’s job performance is more important than turnover (Meyer et al., 1989). Most of the

research (Chen, 2006; Feinstein and Vondrasek, 2001; Kim et al., 2005; McDonald and Makin, 2000; Silva,

2006) has addressed the satisfaction and obligation level of the workers, but only a few of them (Lau and

Chong, 2002; Lok and Crawford, 2004) have considered managers’ viewpoints. However, managers are the core

points of the service production; therefore, their impact on the workers is very important. If the managers are not

satisfied and not obligated to the organization, their effectiveness in managing a Job Performance should be

questioned. Therefore there is a greater need for more research to examine the relationship and effect of work

1

relational outlooks such as organizational obligation and job satisfaction on worker, work results of job

performance. Managers are usually faced with various challenges that require them to remain competitive in

uncertain circumstances. Larger ambiguity may result to higher stress that can cause dissatisfaction and some

other relational and behavioral results among staff at managerial level in business sectors (Jestin and Gampel,

2002). This is no objection to managers an Iranian manufacturing and industrial sector specifically in electrical

and electronic companies. An Iranian confidence on business in this sector which cause d more than 40% in

Growth Domestic Product (GDP) definitely demand them to be always highly obligated and performed (Trade

Chakra, 2010). The following questions regarding the relational and behavioral related outlooks are greatly not

replied to Iranian context: a) whether there is a significant and positive relationship between organizational

obligation and job performance? Does job satisfaction moderate the relationship between organizational

obligation and job performance? In spite of the management staff in Iranian companies and organizations plays

a key role in guarantee the quality services of their customers, there has been a lack of research that addressed

the above topic. This research therefore investigates the above mentioned not replied to questions among

managers of manufacturing companies in Iran. Organizational obligation has been determined and measured

in several different ways due to different definitions and measures in the academic literature. However the

definitions and measures generally share a common subject in that organizational obligation is identified to be a

bond of the individual to the organization. Monday et al. (1982) agree that two observes of organizational

obligation dominate the literature: (1) behavioral outlook and (2) relational outlook. The behavioral approach to

obligation is concerned mainly with the process by which individuals develop a sense of connection not to an

organization but to their own activity. The relational obligation, studied type of organizational obligation

(Mathieu and Zajac, 1990) sees obligation as an attitude reflecting the nature and quality of the linkage between

an worker and organization.

Mowday et al. (1982) define obligation on both affective and continuing outlook which describes a highly

obligated individual as one who has: (1) a strong faith in and acceptance of the organization’s targets and

values; (2) a readiness to use important effort with the knowledge of the organization; and (3) An urge to

support membership in the organization. Mathieu & Zajac (1990) observe obligation as a psychological suggest

that first of all, characterizes the individual’s relationship with organization and secondly has indirect suggestion

for the decision to continue or discontinue membership in organization. Building on these observe points, it is

acceptable to hypothesize that there must be a significant relationship between organizational obligation and

behavioral results such as job performance.Theories seem to maintain that relational factor such as workers

organizational obligation is closely related with job performance. However the findings of past research have

been not decisive. Ward and Davis (1995) discovered a positive relationship between organizational obligation

and job performance. On a research of the relationship between obligation and work results among managers,

Meyer et al. (1989) discovered that the direction of the relationship was based on the type of the obligation.

Meyer and Allen’s (1996) research discovered a positive relationship between affective obligation and job

performance and a negative relationship between continuing obligation and job performance. This finding

shows that although the relationship between obligation and job performance was recognized, but the direction

of the relationship different as a function of the nature of the obligation. Other research reported that

organizational obligation was not related to job performance. This research therefore was to determine the

relationship between organizational obligation and job performance specifically among managers in Iranian

manufacturing companies. Job satisfaction is a contribution of perceptive and affective reactions to the

differential feelings of what and worker wants to accept compared with what he or she actually accepts (Cranny

et al., 1992). According to Mowday et al. (1979), organizational obligation is an attitude, which exists between

the individual and the organization. That is why, it is considered as a relative strength of the individual’s

psychological identification and involvement with the organization (Jaramillo et al., 2005). According to the

organizational studies there are a number of job satisfaction theories which are more that always been referred in

organizational and behavioral studies is Hezberg’s two factor theory (1973).

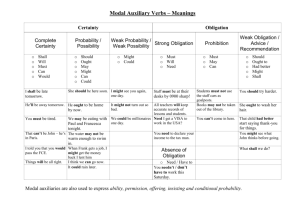

The Hezberg’s theory is based on psychological growth or motivating factors and the need to avoid pain or

hygiene factors. The motivating factors form positive elements that cause regarding job satisfaction and

motivation, while hygiene factors are negative elements that could cause dissatisfaction at work. Job satisfaction

also symbolizes one important type of operation effects and has been related to many organizational behavioral

2

results including job performance (Koys ,2001). The contribution of job satisfaction and its ingredients on work

results has been deeply researched. Earlier literature has stressed more on linear relationship between job

satisfaction and job performance (Ward and Davis, 1995 and Fletcher and William, 1996). According to Rashed

(2001) individuals would expect higher levels of job performance and it has been associated with higher levels

of job satisfaction, although they do not systematically correlate. The discussion suggests that there is a

relationship between job satisfaction and job performance however the nature of relationship is not decisive.

Further less research was investigate on the role of job satisfaction on organizational obligation and job

performance relationship. In addition, for a couple of decades ago organizational industrialists have been

stressed the significance of relational outlooks such as job satisfaction on the relationship between obligation

and job performance and in improving the working environment (Farh et al., 1997and Roberts et al., 1997).

Therefore this study attempted to unravel the inconclusive previous research findings. From motivational

outlook, organizational obligation has been discovered as theoretically associated with job performance (Hunt et

al., 1985, Birnbaum and Somers, 1998). However according to Ingram et al. (1989) empirical studies on the

relationship between organizational obligation and job performance have been less encouraging. Mathieu and

Zajac (1990) discovered that the correlation between obligation and job performance was relatively low but

positive. Although Lee and Mowday (1989) discovered an insignificant relationship has been recognized

between obligation and job performance. This led to the faith that there may be variables that moderate the

relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. Therefore, it is useful in this research to

relate the Hezberg’s dual-factor theory in analyzing organization work results specifically on the organizational

obligation and job performance relationship. Generally, Hezberg’s theory emphasizes the significance of

individual in organization to progress. The progress indirectly will change individual’s needs. As a result it will

help individuals to put extra efforts without stopping to obtain their needs and satisfaction. Looking at the role

and obligation of managers in Iranian manufacturing companies, it is certain that human relation parameters as

explained in the Hezberg’s theory are important in guarantee high performance organization and operation of

organizational targets. At the same time, workers in the organization who find their work profitable and

rewarding would produce and perform better work than those who are dissatisfied. Earlier studies have focused

greatly on direct relationship among organizational obligation, job satisfaction and job performance. However

the effect of job satisfaction on the organizational obligation job performance relationship has not been

investigate widely. More significantly the majority of earlier studies were carried out in non-Eastern settings.

There is a great concern over whether the western business practices theories are related in Iranian private

organizations specifically in manufacturing companies. This research emphasizes the effects of job satisfaction

on the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance among managers in Iranian

manufacturing companies.

2. Hypotheses

The main purpose of this research was to examine the relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance and the measure job satisfaction simplifies the relationship between organizational obligation and

job performance among managers in Iranian manufacturing companies. Therefore the hypotheses assume for

this research are:

H1: There will be a positive relationship between organizational obligation and job performance.

H2: The relationship between organizational obligation and job performance will be moderated by six

motivational aspect of job satisfaction.

H3: The relationship between organizational obligation and job performance will be moderated by eight

hygiene aspect of job satisfaction.

3. Research Method

Participants in the research were the middle and senior management staff of manufacturing companies

specifically in electrical and electronic companies in Iran. A total of 700 questionnaires were sent out to the

managerial staff in the selected companies of Iranian Manufacturer. The selection of the respondent was based

3

on the simple random sampling method. Respondents were given 4 weeks to answer the questionnaires. In all, a

total of 584 useable questionnaires were used in the statistical analysis, representing a response rate of 83.43%

(Table 1). The independent variable of this research is organizational obligation. The Organizational Obligation

Questionnaire (OOQ) was taken up based on a developed instrument by Mowday et al. (1982). The

questionnaire which contains 13 items based on the 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 for strongly disagree to 5

for strongly agree was used to measure organizational obligation. The reliability coefficient of this variable is

.92. The questionnaire of job satisfaction comprised a combination of items adapted from Minnesota

Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss et al., 1967) and Seegmiller (1977). This instrument measures the various

ingredients or aspect of Hezberg’s job satisfaction theory mainly on motivational and hygiene factors.

Motivational factors include: work itself, operation, obligation, progress and identification for operation.

Hygiene factors include, relationship with supervisor, relationship with friends, quality of supervision, policy

and management, job security, working condition and salary. For each of hygiene and motivational ingredient

contains 5 items or statements. The response alternatives for these items were 5 point Likert-scale range from

strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The reliability coefficient for overall job satisfaction aspect scale is

.93. The dependent variable of the research is job performance. Job performance was measured based on

adapted instrument developed by Hind and Baruch (1997) which measured job performance on estimation from

manager or supervisor, self-rating and self-rating as compared to friends. For each of this estimation of job

performance contains 3 items for supervisor rating, and one item each for self-rating and self-rating as compared

to friends. The response alternatives for these items were based on 1 to 5 point Likert-scale, ranging from

strongly disagree to strongly agree. Results were then summarize and divided by 5 to get to a summary

indicator of a workers job performance. Higher mean scores are indicative of greater job performance. In

general reliability coefficient for this scale was .94.

4. Results

Table 1; shows the average age of the respondents in the research is 45.02 years while the mean age of

experience in the organization and in the present job was 10.08 and 7.08 years respectively. Most of the

respondents are married and 33.2% of them are single. Meanwhile 65% of the respondents are male and 37%

are female (Table 1). Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviations and the Pearson’s correlation coefficients

of the research variables. Table 2, shows the mean value for each of the variables and aspect of job satisfaction

changes from as low as 2.64 to as high as 4.35 for the sample involved. The standard deviation for these

variables ranges from 0.52 to 0.89. Job performance, on the other hand, had a mean value of 4.24 with a

standard deviation of 0.77 and the mean for organizational obligation is 3.91 and standard deviation is 0.78. As

can be seen from Table 2, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the dependent, moderating and independent variables

were discovered to be above 0.8 shows that the measurements used in this research were statistically reliable

(Nunnally, 1978). The results show a positive relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. This finding is consistent with expectations and earlier research that there was significant and

positive relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. The results parallel to earlier

findings (Wagner and Rush 2000 and Moses, 1993) giving some support to the construct validity of these

measures. Findings of the research care for suggest that organizational obligation were seen as the stimulator for

management staff in manufacturing companies to do better than in their job performance. The results support the

first hypothesis of the research that there was a positive relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. Therefore the first hypothesis is accepted. The second and third hypotheses of the research were

tested using hierarchical retrogression analysis to determine the effects of job satisfaction on the organizational

obligation and job performance relationship. A hypothesized mediator effect is supported if the interaction terms

significantly increase the variance explained by the predictors (Cohen and Cohen, 1975). Based on this method

the organizational obligation was record in the first step, followed by the moderating variables in the second

step. In the third step, the interaction terms were record. Table 3 describes the effects of job satisfaction

(motivational factors) on the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance while Table 4

describes the effects of job satisfaction (hygiene factors) on the relationship between organizational obligation

and job performance. As arrange in Table 3 it was discovered that the model variables together with the

moderating variables of job satisfaction (stimulator factors) could jointly explain 64% of variance in job

performance. Organizational obligation was discovered to have a significant and positive effect on job

4

performance (b =0.24, p < 0.05).The retrogression coefficient for job satisfaction (motivation factors) of work

itself (b =0.30, p < 0.05); operation (b =0.25, p < 0.05); possibility for growth (b =0.26, p < 0.05; obligation (b

=0.15, p < 0.05); progress (b =0.24, p < 0.05) and identification for progress (b =0.27, p < 0.05) were

discovered to have a significant and positive effect on job performance. In examining the interaction terms, all

of the job satisfaction aspect (stimulator factors were discovered to be the mediator of the relationship between

organizational obligation and job performance. When the interaction terms for stimulator factors were record,

the incremental variance in job performance of 15% was discovered to be significant (p < 0.05). This shows that

all of the stimulator factors did moderate the relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. The results suggest that if obligated workers are made happy by improving the stimulator factors

in the work place, they would be willing to give the best of their services to the management and increase their

job performance. An examination of the full model from the block of interactions in Step III show that variable

identification for operation was discovered to be the highest interaction effect of organizational obligation on

job performance (b =0.55, p < 0.05.) followed by variables of progress, work itself, obligation and operation.

Therefore, the increase in interaction effect of motivating factors showed that all of the five stimulator variables

explaining important variations in job performance and suggests that the job performance of obligated workers

will be high if the levels of satisfaction with these job satisfaction aspect in which they are interested are

increased. The results confirm the second hypothesis of the research. Therefore the second hypothesis is

supported. As for the third hypothesis it was discovered that the model variables together with the moderating

variables of job satisfaction (hygiene factors) could jointly explain 67% of variance in job performance.

Organizational obligation was discovered to have a significant and positive effect on job performance (b =0.43,

p < 0.05).The retrogression coefficient for job satisfaction (hygiene factors) of status (b =0.37, p <

0.05);relationship with supervisor(b =0.23, p < 0.05); relationship with friends(b =0.19, p < 0.05); quality of

supervision(b =0.23, p < 0.05); policy and management(b =0.27, p < 0.05); job security(b =0.16, p < 0.05);

working condition (b =0.18, p < 0.05) and salary(b =0.48, p < 0.05) were discovered to have a significant and

positive effect on job performance. An examination to the interaction terms showed that all of the job

satisfaction aspect (hygiene factors) was discovered to be the mediator of the relationship between

organizational obligation and job performance. When the interaction terms for hygiene factors were record, the

incremental variance in job performance of 24% was discovered to be significant (p < 0.05). This shows that all

of the hygiene factors did moderate the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. The

results suggest that if obligated workers are made happy by improving the hygiene factors such as in terms of

salary, they would be willing to give better services to the organization which will increase high job

performance. An examination to the interaction terms showed that all of the job satisfaction aspect (hygiene

factors) was discovered to be the mediator of the relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. When the interaction terms for hygiene factors were record, the incremental variance in job

performance of 24% was discovered to be significant (p < 0.05). This shows that all of the hygiene factors did

moderate the relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. The results suggest that if

obligated workers are made happy by improving the hygiene factors such as in terms of salary, they would be

willing to give better services to the organization which will increase high job performance. The results also

showed that the full model from the block of interactions in Step III show that variable salary was discovered to

be the highest interaction effect of organizational obligation on job performance (b =0.57, p < 0.05.) followed

by variables of job security, working condition, policy and management, quality of supervision, relationship

with friends, relationship with supervisors and status. The increase in interaction effect of hygiene factors

showed that all of the eight hygiene variables explaining important variations in job performance and suggests

that the job performance of obligated workers will be high if the levels of satisfaction with these job satisfaction

aspect in which they are interested are increased. On the whole based on step III the increase in interaction

effect of hygiene factors indirectly suggested that those who seen highly obligated and satisfied with seven

hygiene factors are performing better in their job. This results support the third hypothesis of the research.

5. Concluding

The main purpose of this research was to examine the relationship between organizational obligation and job

performance. The second and third objective in the research was to determine the moderating effects of job

satisfaction (stimulator and hygiene factors) on the relationship between organizational obligation and job

5

performance. The findings of the research were in the hypothesized direction as organizational obligation was

related to increased job performance. As a result the research concluded that job satisfaction simplifies the

relationship between organizational obligation and job performance. The main contribution of this research was

the moderating effects played by the motivational and hygiene factors in the organizational obligation-job

performance relationship. The findings of the research implied that the manager of Iranian manufacturing

companies who are obligated to their organization are likely to perform better in their jobs if the level of

satisfaction both on hygiene and stimulator factors they accepted were improved. This findings care for point to

the fact that the Hezberg’s theory is a possible model in the organizational obligation-job performance

relationship. The results of the research support those by earlier researchers (Birch and Kamali, 2001), thus the

present research confirms the result obtained by these researches and conclude it to the other groups of workers.

This is the first issue dealt with in this research that has not been stressed in earlier studies especially among

managerial levels in Iranian manufacturing companies. Earlier studies were usually conducted in western

setting. The research showed here presents that western management and organizational theories could be valid

in a non-western setting and the findings discovered in a certain society can be clear in a different society. This

research should not be an end in itself therefore possible expansions of this paper could be investigated. It would

be interesting to test the responsiveness of the findings to using other measures of policy and behaviors in

organization or to take advantage of more than one measure of organizational obligation. Robustness can also be

validated through using different samples in a variety of settings. The impacts of other variables on the

relationship between organizational obligation and job performance could be further investigated to confirm the

findings of the research.

References

Birch, T.A, and Kamali, F., 2001. “Psychological stress, anxiety, depression, job satisfaction and personality

characteristics in pre-registration house officers”, Post Medical Journal 77, pp 109-121.

Birnbaum, D and Somers M.J, 1998. “Work-related commitment and job performance: It’s also the nature of

the performance that counts”, Journal of Organizational Behavior 19, pp 621-634.

Chen, C.F. (2006), “Short report: job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and flight attendants’ turnover

ıntentions: a note”, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 12, pp. 274-6.

Cohen, J. and Cohen P., 1975. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral science.

Hilldale, New Jersy : Erlbaum.

Churchill, G.A, Ford N.M and Walker O.C., 1993. Sales force management, R.D. Irwin: Homewood.

Cranny, C.J, Smith R.C. and Stone E.F., 1992. Job satisfaction: How people feel about their jobs and how it

affects their performance. New York: Lexington.

Farh, J.H, Earley P.C. and Lin S.C, 1997. “Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational

citizenship behavior in Chinese society”, Administrative Science Quarterly 42, pp. 421-444.

6

Feinstein, A.H. and Vondrasek, D. (2001), “A study of relationships between job satisfaction and organizational

commitment among restaurant employees”, Journal of Hospitality, Tourism, and Leisure Science, available at:

http://hotel. unlv.edu/pdf/jobSatisfaction.pdf (accessed April 15, 2007).

Fletcher, C. and William R., 1996. “Performance management, job satisfaction and organizational

commitment”, British Journal of Management 7, pp 61-81.

Hezberg, F., 1973. Motivation: Management of success. Elkgrove Village, Illinois: Advanced System Inc.

Hind, P. and Baruch Y., 1997. “Gender variations in perceptions of job performance appraisal”, Women in

Management Review 12, pp. 1-17.

Hom, P.W. and Griffeth R.W., 1995. “Employee turnover”, Community Psychiatry 35, pp. 56- 60.

Hunt, S.D, Chonko L.B. and Wood V.R., 1985. “Organizational commitment and marketing”, Journal of

Marketing 49, pp. 112-126.

Ingram, T.N, Lee K.S and Skinner J, 1989. “An assessment of sales person motivation, commitment and job

outcomes”, Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management 9, pp. 25-33.

Jaramillo, F., Prakash Mulki, J. and Marshal, G.W. (2005), “A meta-analysis of the relationship between

organizational commitment and salesperson job performance: 25 years of research”, Journal of Business

Research, Vol. 58, pp. 705-14.

Jestin, W. and Gampel A., 2002. The big valley, global outlook. Toronto: McGraw Hill.

Kim, W.G., Leong, J.K. and Lee, Y. (2005), “Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational

commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant”, Hospitality Management, Vol. 24, pp.

171-93.

Koys, D.J., 2001. “The effects of employee satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, and turnover on

organizational effectiveness: a unit-level, longitudinal study”, Personnel Psychology 54, pp. 101-14.

Lau, C.M. and Chong, J. (2002), “The effects of budget emphasis, participation and organizational commitment

on job satisfaction: evidence from the financial services sector”, Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research,

Vol. 5, pp. 183-211.

Lawson, E.W. and Fukami, C.V., 1984. “Relationship between workers behavior and commitment to the

organization and union”. Best paper at the 44th annual meeting of the Academy of Management, New Orleans,

Lousiana.

Lancaster, G. and Jobber D., 1994. Selling and sales management. London: Pitman

Lee, T.W. and Mowday R.T., 1989. “Voluntary leaving an organization: An empirical investigation of Steers

and Mowday’s Model of Turnover”, Academy of Management Journal 30, pp.721-743.

Lok, P. and Crawford, J. (2004), “The effect of organizational culture and leadership style on job satisfaction

and organizational commitment: a cross-national comparison”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 23

No. 4, pp. 321-38.

Mathieu, J and Zajac D., 1990. “A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of

organizational commitment”, Psychology Bulletin 108, pp. 171-194.

McDonald, D.J. and Makin, P.J. (2000), “The psychological contract, organizational commitment and job

satisfaction of temporary staff”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 84-91.

7

Meyer, J. Paunonen S., Gellatly I., Goffin R. and Jackson D., 1989. “Organizational commitment and job

performance: it’s the nature of commitment that counts”, Journal of Applied Psychology 74, pp. 152-156.

Meyer, J.P and Allen N.J., 1996. “Affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization: An

examination of construct validity”, Journal of Vocational Behavior 49 pp. 252-276.

Moses, M.R.L., 1993. “Organizational commitment and job performance among operators of selected electrical

and electronic industries in Kalang Valley”. Unpublished Phd dissertation: Universiti Putra, Malaysia.

Mowday, R.T, Porter L.W, Steers R.M., 1982. Employee's organizational linkages: The psychology of

commitment, absenteeism and turnover, New York: Academic Press.

Mowday, R.T., Steers, R.M. and Porter, L.W. (1979), “The measurement of organizational commitment”,

Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 14, pp. 224-47.

Nunnally, J., 1978. Psychometric Theory, New York: McGraw Hill.

Rashed, A.A., 2001. “The effect of personal characteristics on job satisfaction. A study among male among

managers in the Kuwait oil industry”, International Journal of Commerce & Management 11 pp. 91-111.

Robbins, S.P., 2005. Organizational Behavior, 7th Ed. Pearson Prentice Hall: New Jersey.

Roberts, J.A., Lapidus R.A. and Chonko L.B., 1997. “Salesperson and stress: The moderating role of locus of

control on work stressors and felt stress”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 5, pp. 93-108.

Seegmiller, J.P., 1977. “Job satisfaction of faculty and staff at the College of Eastern Utah”. Unpublished Phd

dissertation: College of Eastern Utah.

Silva, P. (2006), “Effects of disposition on hospitality employee job satisfaction and commitment”, International

Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 317-28.

Steinhaus, C.S. and Perry J.L., 1996. “Organizational commitment: Does sector matter?”, Public Productivity &

Management Review 19, pp. 278-288.

Trade Chkra: http://www.tradechakra.com/economy/malaysia/human-resource-in-malaysia-155.php, accessed

on 11 December 2010.

Questionnaire. Work Weiss, D.J, David G.W, Lofquist L.H., (1967). “Manual for the Mannesota Satisfaction

Adjustment”, Industrial Relations Center: University of Minnesota.

Wagner S, Rush M.C., 2000. “Altruistic organizational citizenship behavior. Context, disposition and age”,

Journal of Social Psychology 41 pp. 108-391

Ward, E.A. and Davis E., 1995. “The effect of benefit satisfaction on organizational commitment”,

Compensation and Benefits Management 11 pp. 35-40

Table 1: Summary of Profile of Respondents

8

SD

6.57

6.91

3.29

-

Mean

45.02

10.08

7.08

-

Age

Experience in the organization

Present job experience

Male

Female

Married

Single

n

372

212

394

190

%

65

37

67.1

33.2

Table 2: Correlation Matrix of all variables

Mean

3.44

4.35

2.87

3.27

2.63

3.58

3.99

3.48

3.64

4.22

3.99

3.91

4.24

S.D

0.76

0.48

0.79

0.79

0.89

0.78

0.78

0.77

0.89

0.71

0.85

0.78

1

.80

.17*

.33*

.26*

.23*

.16*

.43*

.44*

.35*

.38*

.32*

.39*

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

.80

.63*

.65*

.64*

.44*

.45*

.46*

.68*

.34*

.33*

.51*

.84

.33*

.44*

.51*

.50*

.44*

.37*

.35*

.57*

.34*

.86

.31*

.29*

.55*

.59*

.40*

.66*

.35*

.40*

.89

.56*

.51*

.46*

.50*

.69*

.50*

.53*

.93

.45*

.40*

.38*

.36*

.49*

.39*

.89

.35*

.38*

.33*

.40*

.52*

.81

.22*

.36*

.32*

74

.35*

.39*

.85

.47*

.73

12

0.77

.29*

.43*

.66*

.45*

.41*

.33*

.49*

.54*

.47*

.39*

.60*

.92

*p = 0.05, alpha reliability values of variables. 1. Work itself 2. Possibility for growth 3. Responsibility 4.

Recognition (motivational facets)} {5. status 6. relationship with supervisor 7. operation 8. working condition 9.

salary (hygiene facets)} 10. Relationship with friends 11. Organizational obligation. 12. Job performance.

9

Table 3: Hierarchical Retrogression Analysis Predicting Job Performance of Workers by Motivator Factor

Independent Variable

Model Variables

Organizational obligation

Moderating Variable

Motivator factor:

Work itself (Wis)

operation (Ope)

Possibility for growth (Pg)

Responsibility (Res)

Recognition for advancement (Ra)

Interaction Terms

OO X Wis

OO X Ope

OO X Pg

OO X Res

OO X Ra

R2

Adj R2

R2 Change

Sig. F Change

P < 0.05

10

Std Beta Step 1

Std Beta Step

2

Std Beta Step

3

.15*

.24*

.33*

.30*

.25*

.26*

.15*

.27*

.41*

.38*

.26*

.39*

.64*

0.59

0.64

.18*

.29*

.38*

.37*

.55*

0.76

0.56

0.59

10.90*

0.61

0.07

21.35*

0.73

0.15

18.60*

Table 4: Hierarchical Retrogression Analysis Predicting Job Performance of Workers by Hygiene Factor

Independent Variable

Model Variables

Organizational obligation

Moderating Variable

Hygiene factor

Status (Sts)

Relationship with supervisor (RS)

Relationship with friends (Rf)

Working Condition (WC)

Salary (SL)

Interaction Terms

OO X Sts

OO X Rs

OO X Rf

OO X WC

Std Beta

Step 1

Std Beta Step 2

Std Beta

Step 3

.17*

.43*

.46*

.37*

23*

.19*

.18*

.48*

.65*

.25*

.22*

.18*

.50*

.17*

26*

.40*

.53*

11