Word

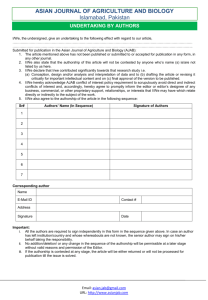

advertisement