richie_transcript - Conversations with History

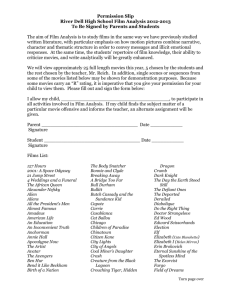

advertisement

Background Mr. Richie, welcome to the Bay Area. Thank you. Where were you born and raised? I was born and raised in a town in Ohio called Lima. And what was it like growing up in Lima? Oh, it's like ... really, wherever you grow up is pretty much alike. I suppose what counts is how you react to your growing up wherever you are. I mean, many people are still in Lima who were born at the same time I grew up, and a number of us are no longer there. So I think what you do is you learn what you learn where you were born, and then, if it suffices, very often you don't have a reason to do anything further; and if it doesn't, then you go out and find a place that does agree with you more. How, in retrospect, do you think your parents shaped your character? I think that parents shape character, negatively or positively, no matter how they intend to do it. I think that the child picks and chooses, too, a lot. I don't subscribe to the parents' responsibility in the raising of the children all that much. My mother once asked me, if she had been a better mother, would I have turned out differently? And I had to tell her that she shouldn't read anymore ladies' magazine psychology, that everything's my choice. You may not be presented with an à la carte menu, but you do have a table d'hôte. Any child, anybody growing up, has a choice, and he or she makes this choice. I made all my own choices. My parents may have done some things which made my choices more dramatic, like leaving home or going abroad, or staying the rest of my life in another country. But I can't hold them responsible, those are my choices. Did you have any teachers or mentors even when you were still in Lima that influenced you? I suppose you can call it one of my problems: I didn't have any role models. Boys -- girls too, I suppose -- are supposed to have some sort of role model. My family was so situated that I didn't have anybody, and my school was such that there was nobody that I chose or that chose me. And so my role models came from the books I read, the movies I saw. I don't believe I really had any life role models until I was sort of grown up. Movies You mentioned books and movies [as] formative experiences for you. Tell us about going to the movies -- the Sigma, I think, was the name of the theater. The Sigma was the theater, yes. I guess the movie house was a place that brought the world to you, is that the way it was? I guess you could say so. What happened was that sometimes I was, from a young age, put in the [theater to watch] movies because they kept me quiet and they kept me entertained, and they got me out from under the feet of my parents. So from a very early age, I went to the movies and I soon grew to prefer the life of the movies to my own life. The reality that the movies offered was preferable to the reality that I was experiencing. I became a child movie addict. I would go in with great pleasure and I'd never look at what was playing -- what was playing was unimportant. The fact was that I was entering a new world, an environment where not only was it much more attractive than my life was ordinarily, but also I could manipulate it to an extent by coming and going, and by looking at scenes or not, which I could not in my own life. I was subjected to my own domestic life. But I discovered a kind of power at the movies. When I started to learn how to read, I discovered the same kind of power. I could create an environment that I didn't have, and I could order this environment in the way that I couldn't in my actual life. Then, when I learned to write, I learned that I could do this not only for myself, but for other people. I could create whole things that were believable, at least to myself, at that point. And in this way, I began to wield an authority and a power that I had not had before. In other words, every child goes through this. Some pick football and some pick the library. I picked the library. So, both in words and in the images on the screen in movies, you were presented with alternative realities that you could choose to do things with in your own mind. Is that fair? In a way it sounds like you were empowered by these experiences. Precisely. That's the word. What was it about your own environment that was wanting, do you know? Well, obviously, that I wasn't empowered. I mean, no child is empowered. That's why teenagers act the way they do, all this "cool" business is signs of an empowering they don't have. In my case I was ... I don't know if I was less empowered than anybody else my age during those years. But anyway, empowering the child was not one of my parents' concerns. What sort of things did you learn at the movies that empowered you? One learns a great deal from the movies. One learns comportment, one learns philosophy, one learns metaphysics, and one learns the meaning of life. I suppose that when one goes to the movies, it sort of seeps in through osmosis, and one learns a lot without knowing it -- even the latest violent flick, one does still does learn something. If you go to a film that thinks, then you learn a great deal more. I think this is true of the appeal of the films. I think that people approach films not only as an escapist drama of one kind or another. These are the great cathedrals of learning. People learn things. I remember in high school, some girls watched how June Allyson went down the steps, which was very graceful. And soon they were all doing it. Betty Grable taught me how to make eggs. You do use it for learning. I mean, role models: Gary Cooper taught me always to be noble and honest. And Johnny Weismuller taught me how to yodel and go through trees! You learn things, right? You talk in your most recent collection about a moment at the film where a bad projectionist was screwing up the showing of Citizen Kane, and -That's what I thought, yes. ... what you thought, correct. And then, tell us how you responded to that experience as it was happening. And what was chaos, in a way, turned into order for you, I believe. Well, seeing Citizen Kane was one of the great and seminal experiences for almost everybody in my generation, at least, anybody who went to the movies. I had wandered into the Sigma Theater again; again, not looking at the marquee, having no idea. And the film started, and it was some old guy who was in bed dying. It's the way that RKO films often started, so this did not surprise me. But then all of a sudden, on came the newsreel. And then I realized that our projectionist, who had a reputation for drinking, had been at the bottle again, and he had put the newsreel on after the movie had started. So I sat through that. And then I wondered, also, that he must have mixed up the reels, because the time structure was quite different from the steady plotting, narrative chronology that I had grown to expect. It wasn't until the film was ending that I'd realized that the man was dead sober and this was all intentional. So I didn't leave the theater; I sat through it again. In fact, I was late for supper that night because I'd seen Citizen Kane three times that day. It had the effect of dropping the scales from my eyes. It made me see. It made me not only see Charles Foster Kane's life, but also see my own life by contrast, and also give me an idea of the extraordinary power of film and what film could do. I'd never seen a film which was "all film" the way that Citizen Kane was. So in this case, on a number of levels, it affected me and all of us who saw it -philosophically, metaphysically, technically, cinéastely -- on all of these levels, I walked out a new person. I became a filmmaker. I was so intrigued at the possibilities that I went to my father and said I wanted a camera. How old was I? Seventeen? And my father got me a 8-mm camera. I went out the very next Sunday and invented the documentary. I'd never heard of it, but I took pictures of the church and people coming out. I was going to call it Small Town Sunday. I started my film career hands-on, thanks to Citizen Kane. And that movie and other movies, what else should we know about what movies can do for us, beyond empowering us? Oh, movies can do anything that life can do. They can move you, they can teach you, they can make you meditate, and they can make you dream. They can do everything that life can do. They're a simulacrum. This is their great power. Writing Now, in addition to movies, it was in Lima that you found the power that words have. Tell us about that, your relationship to reading and to words, and to writing. Well, as you can imagine, going to the movies all the time, escape was one of my concerns. Escapism is how the movies have been often defined. And they're excellent escape material -- you simply climb on and reel off, and you're not there anymore. In the same way, books can also do that. You climb on the pages, the pages flap and away you go. So when I first learned to read, I was into much escapist literature. I read The Little Lame Prince, for example. That's the cloak that he rides in -- and Arabian Nights, The Wizard of Oz, the Edgar Rice Burroughs books -- all of these offered kinds of escape, often into violent environments that were quite the opposite of my own. I perfected, eventually, the means of escape; that it needn't be quite as wild as that. Before very long I was reading Booth Tarkington, and popular favorites of the day -- Little Men, Little Women -- that kind of thing. It was only later on, of course, that I got into literature. I didn't have much literature. I was mainly into escape material; I knew all about that, since the movies had given me an escape hatch, too. Using it this way, I became interested, technically, in exactly how the escape was effected. I decided that a kind of precision was necessary. And so I remember one day when I was feeling -- not, I couldn't say, creative; but I was feeling sort of -- it was raining and I couldn't go outside and there were no movies, and I couldn't get to the library. And I remember, I must have been about seven or eight, I picked up a yellow pad and looked out the window and decided to sketch, in words, what I saw. I sketched the color, the rain, the wetness, the general dankness, the general dreariness of it. And then I wondered exactly what it was that I had done. I remember getting down the Webster's and looking up things. And I came across the word "elegy," which appealed to me very much and even looked like I felt -- the two little e's like half-closed eyes. I realized that what I had done was something elegiac, which was a completely new word for me. I read it over and I, again, felt what I had felt when I [first] read it. I had created Hemingway's ideal. I had written an impressionistic piece of prose that gave the reader the impression that the writer had intended. I made the reader feel what I wanted him to. This was a revelation to me because it not only empowered me, it also seemed to give a sort of a magical way of communication that had nothing to do with my being more powerful than anybody else, but allowed me to suddenly illuminate something. It was a metaphysical triumph at eight years old, all of which I only recognized later on. And so, words having done all this, I instantly started -- just as I went gung-ho on Citizen Kane -- I instantly started writing a novel. I was at the kitchen table that night scribbling - whatever happened to it and what it was about, I have no idea. But anyway, all of these things are good practice. And so my conjunction with words started quite early that way. And it had a number of levels. And what were those levels? Well, they were certainly "empowering," "escaping" -- high on the priority list -- but also "communicating," whatever that means. Also, teaching me to meditate upon my own feelings, which I had never had any occasion to do, except to express them. In general, it was a very flowering occasion for me. It also gave me a way in which I had hope -- I thought, maybe, I was doomed for life in Lima, Ohio; and it gave me reason to believe that there were ways, using my new tools, that I could move into something more congenial. One minor point, which we should emphasize. You were also a very good typist, which became very important later. That came later. Typing was the other thing which liberated me. If a person can't type, I don't see how you can be a writer -- nowadays, certainly. I mean, I can imagine Thackeray or Jane Austen sitting down and scribbling, but for anybody in my generation, learning the machine, which is now, of course, the computer, is something which is necessary. I am very fond of things like that -- little, small mechanical things -- and I'm a very good librarian, I've worked at being a librarian. I'm very good at collating, the Dewey Decimal system -- I have that side of me. Typing fit into that. Before very long, without even thinking of it, I was a speed typist. Now, the other element, the other theme that we must bring up is moving on, getting out, which became very important. What you just said suggested a kind of dissatisfaction with your milieu, pushing you. These tools, namely, insight about film and actually having your own camera, on the one hand, and writing on the other, empowered you to feel that you could do it. Was it inevitable that you would leave? And how did you go about leaving? First, there is an American thought, which I think is true, that anybody worth his or her salt, leaves. Japan has the opposite idea, where, if you do that, something is the matter with you. But in America you have to leave. There are all sorts of precedents. I think everybody wants to leave, it's just this question of whether you can or not. At the age of eighteen or nineteen you find very few people who want to stay there forever. They've already got plans -- you know, you want to get out. So if you have the means to get out, then you get out. In my case, I was early inspired to leave my milieu and to find something more like what I found in books or in the movies, or something that I felt would fit me more. There were several incidents, several ways that I discovered [this]. I read a book about 1939 that inspired me a lot. I don't know if it's readable now. It's called The Asiatics by Frederick Prokosch. And so I was alert to Prokosch. Later on, I read a book of his called The Night of the Poor about some boy, misunderstood, from this stifling middle-west town, who gets out, puts out his thumb, and hitchhikes all over America. And I did that. No sooner had I graduated than -- with my parents' blessing, to be sure -- I stuck out my thumb on Route 30 and went south, went to New Orleans, all by myself. But then you joined the Merchant Marine? Well, that was due to the war. I probably wouldn't have done that if the war hadn't come, and if I hadn't been about to be drafted. This we didn't want to occur! This was 1942. I joined the Merchant Marine the day before I got inducted. Then you went to different parts of the world? I went all over the world. I made it to Europe. You know, the Merchant Marine, at that point, was supporting the troops. The troops would go in first, but we would come in, two hours later, with all the chocolate bars and the toilet paper. We supported them. Our work was really just as dangerous, in a way. I mean, we didn't get shot at and we didn't carry guns, but we did have to go on convoys in the North Atlantic, where I would lie awake trying to read Proust, and I would hear "Boom! Boom!" And that would be the two end ships of our convoy being sunk in the North Atlantic during a storm by German submarines. So it was dangerous, and I lost my ship, various ships, three or four times. And then as the war ended in Europe, the alliance I was with went to Asia, and so I was in China when the war ended. Were you keeping diaries during this time? I was keeping diaries. I started keeping diaries very early. They all have titles, like Fifth Voyage, Seventh Voyage, and so forth. During this time, from the time you started writing to being in the Merchant Marine, were you honing your writing skills? Was your writing getting better in your own mind? I hoped so. I hoped so, yes. Japan: Discovery So how did you wind up in Japan? You last left us in China. Did one of your ships come to Japan and you decided to stay? No. What happened was, the war was over, I was back home. My escape route was cut off. The only place for me to go was back to Ohio. I was unwilling to do that. I heard that the foreign service was accepting people for the two occupied areas, which were Germany and Japan. I signed up, and being a very good typist, I was taken. I put down Germany because I had been all over Europe, but I had never been to Germany. But they, in their wisdom, sent me to Japan. And so on the last day of 1946, I sailed into Yokohama harbor. What sort of typing did you do? You worked for the civil administration there? Yes, I worked for a certain part of the Occupation, which was concerned with war repatriations. I thought it would be all about Tang horses and pearls and things. But it wasn't. It was just lists in triplicate. No matter what a good typist I am, I'm not particularly fond of that talent. So I determined to get out, and I went to Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper, and did a few articles for them on spec as it were, kind of human interest articles, people living under bridges and things like that. And they liked it. The occupation had humanized itself enough that people living under bridges were now something one could read about. So I was put on the staff, and I became a staff writer. I pointed out they didn't have a film critic, and they agreed, and so I became it. To be sure, I didn't review any Japanese films -- we were not allowed in the theaters. But I reviewed Betty Grable for the troops, that sort of thing. Let's talk a little about reviewing American films. After all of this traveling, did you see American films differently? Were you more conscious of the way they were because of these experiences? Oh, yes, of course. When I first saw Betty Grable, for example, I treated her like sort of a more favorably inclined mother. And -This is in Lima, when you were young? In Lima, yes. She would teach me things. I remember in Moon Over Miami, she taught me how to make gas-house eggs, which is where you take the piece of bread and put a hole in the middle, put the egg in and turn it over -- gas house eggs -- which I would then make. So I would learn something that way. Later on, when I was in Japan and was reviewing Betty Grable for the troops, of course, I did not see her as an ersatz mother anymore, nor as a teacher of how to make food. I then saw her as an icon for the troops. My interest had become much more generalized, and I was able to talk more or less learnedly about the effects she was having on the troops, the fact that there's a whole line of such icons in the films that are used for various political purposes. And I could connect her to Theda Bara and [others]. I could do this sort of thing by now. When you look back at any of these writings, do you still have pride in them? Thank God I don't have to look at them. I see. The entire collection is at the Museum of Modern Art. I haven't seen it for years. I see. So somebody who wants to do a book or a dissertation on you might want to go there. Now, at a certain point you weren't supposed to movie house and watch a that? And what was that here you get the idea to do what do, which was to go to a Japanese Japanese movie. Why did you do experience like? Well, the reason I went ... of course, there are a number of reasons why one does things like this. Our life there was circumscribed in a way which was rather like Lima. There were a number of things one couldn't do. "No fraternization with the indigenous personnel" was still a sign that you saw. And, of course, anybody with any American spirit in them would want to break such a law. We all did that. And if you did and the MPs caught you, then you were reprimanded. But if you were clever, they didn't catch you. And the kabuki, the coffee shops, the bordellos -- they were all off limits, and the motion picture theaters were all off limits, and I could live without kabuki or bordello, but I really, at this point, couldn't live without film. And besides, film, I knew, was a great teaching tool. I was in this new country and I wanted to learn something about it. I already knew that I understood my own country through films, and it seemed like I could look at Japanese films and I could learn something about the country. So I used to go to places where the MPs weren't, and then sneak in and stand in the back and look at these films. All in a language I could not understand, but when you look at films and don't have titles, and have no idea if it's a mother or a lover that the hero's involved with, you learn something else. You learn about the choices that a director has, you learn about why he makes the movements that he has, you're undistracted by story, you're undisturbed by understanding dialogue -- all of these things give you another way of learning, another way of finding out -- which in the case of film is more true. And so you learn exactly what the director wanted to do and then you can judge how well he did it. So in a way, not knowing the language of the Japanese, you learned even more the language of their cinema. Yes. And through the language of their cinema, you learned the other more important language of ... oh, the body language, the moves, the looks, the expressions, the assumptions -- all of this you learn. Narrative, and understanding it, would only have been an impediment to this. You've written several studies of Japanese cinema and you've written about two of its most famous directors, Ozu and Kurosawa. Tell us a little about your conclusions about Ozu and how very different he was from most American directors, if not all American directors. Well, paradox is involved, because Ozu learned probably more from American cinema than anybody else. But he learned from the cinema of the twenties -- from the popular cinema. So, if it hadn't been for Our Gang, we probably wouldn't have great child comedies like I Was Born, But.... The paradoxical thing is that he took these very means and turned them to his own uses. He took the means of primitive cinema and put them to the most sophisticated uses, which would include things like allowing no pans, allowing no dollies -- cameras on wheels -- allowing only one form of punctuation, which is a straight cut -- that is, no dissolves, no fades-in/fades-out -- and making an extraordinarily stringent, majestic kind of film, which in its way is not too different from the films of 1918, except they are done with a degree of sophistication which the West has yet to match. Which allows many a critic -- Japanese, as well as Western -- to talk about the "haiku-like" structure, the economy of means which they find Japanese -- the use of space, which is found to be Japanese. And it is Japanese, as far as I know. But the point is that it's more Ozu than it is anything else. And it is these things which make his cinema the contained experience that it is. Kurosawa, on the other hand, also learns from the West. He's very fond of John Wayne, for example. He's fond of the Western people and of the Western genre. And so he's able to, again, move all of these things into his own vision of his own world, which, again, is completely unique. But this is uniqueness on one side, which is Kurosawa's, and one which is Ozu's. You say at one point that Ozu doesn't want to show the story, but how his characters react to what happens in the story and what patterns these relations create. I said it. And so it's really this -- and I fear I won't do justice to what you're saying -- but this very simple, empirical presentation of an everyday life is done in such a way that we come to see patterns to which we react. And you're saying that it requires a lot of the viewer. His simplicity makes our job more complex. Or makes our job more rewarding. Yes, both, yes. He builds his half of the bridge; we build ours. This is a modernist trait. And, indeed, one can see and one has seen Ozu as a modernist. That is, if you remember how Gertrude Stein, for example, or T.S. Eliot, or Henry Green write, they write in a way which the ordinary reader might find oblique, but if he moves toward them, he will find to be more rewarding than not. In the case of Henry Green, for example, one is presented, much as in Ozu, with these geometrical blocks. And it is of these that one makes one's own sense in creating a narrative. But you have to bring your attention to it, because Ozu very often proceeds at a deliberate pace. And while he may seek to lose you, it's always for playful purposes, never seriously seeking [to lose you]. If you look at Tokyo Story, for example, and examine the chronology, you will see there are many places where time and space are played with. The discreet blocks of the narrative remain there, but are yours to interpret. And, in fact, if he has anything really important like a wedding, he'll be just like Jane Austen, he'll leave it out. She is also a modernist, which is why we like her so much. This very discreet way of communicating is something which the modernists -- and I'm talking of the school from 1920 to 1940, let's say -- learned to do. Ozu knew all of this. There was a big modernist school in Japan -- Kawabata is part of this. He used these techniques, coupled, again, with primitive means to lend a "quotidian" quality. I suppose that's the word I would use, mainly --as in Vermeer. I mean, it's all milk jugs, but it's magic, you know. The same way with Ozu's: it's just a red coffeepot, but it's magic. How have you contributed to making the depth and complexity of Japanese cinema available to the West? You know, sometimes people say that I'm the man who introduced Japanese cinema. And this is not true. I mean, many people did this. Joe Anderson and I, when I wrote our first book ... we did write the first complete menu, so you don't know what's on the table until you read our book. Right. And so in that sense, and also in the sense in that my later books have sought to disclose whole fields, and to connect them to the sociology or the anthropology of Japanese life. All of this which it gives the reader a context, which they hadn't had. People ask me what I am, and I say I'm a film historian. I guess that's what I am. Finding a Voice as an Expatriate Writer It's really in Japan, writing about Japan as an expatriate, writing about film in Japan, that you found your voice as a writer. Yes, I think so. Everybody finds his subject, whether he knows it or not. I had certainly never, when I first started writing, thought that I would find a country as my subject. I knew it probably wouldn't be Lima that I'd write about, but I had no idea that I'd go to the antipodes and discover my subject there. And, in fact, when I was living there and writing -- it isn't until recently that I have really come to the realization that that is my subject. You know, Henry James used to speak about what one's subject is. He realized that his subject was expatriation. And I do, too. There's a whole American school -- Edith Wharton, Hemingway to an extent, Ezra Pound, certainly, Eliot -- of people who are quite aware of their expatriation. And they use this in those creative kinds of ways. I don't compare myself to these people, but our ways of confronting our lives have some similarities. You find satisfaction, you are attracted by this role of somebody who is an outsider but who is engaged in writing. Is that a fair statement? Yes. I would enlarge a little bit. I have chosen a particular place where the foreigner, as a rule, is not welcome. Some people go to Japan wanting to become Japanese themselves. This is a great error, since this will never occur, since Japanese would never allow this. The Japanese are xenophobic to an extent. This, I have discovered, fits me very well. I became very used to this marginalized position in little Lima, and it has become a vice of some largeness, that I see myself as always ... I see alienation as a very positive, powerful, beautiful thing. It's like being on a mountain range and you look back where you came from and the foibles of where you came from can't reach you anymore. And then you look down to where you are regarding, and you can't go down there. You have the best seat in the house. You don't belong to anything. You're a social unit of one. I cannot think of anything more free or more enlarging than this. You don't belong to anybody, except yourself. You go on to say that the act of comparison, which is presumably involved here also, is the act of creation. "I'm at home in Japan, precisely because I'm an alien body." There you see, I said it again. It's my theme song. That's right. But it is this having a benchmark, having something to compare that really is important. Sure. You look here and you look there, a perfect view, and you're in a perfect position to compare and to describe this lack of coordination or this ... sometimes coordination. You can describe. I think being able to describe something is the highest human goal. There's a lot of that in your writing. I hope so. How do you write? Is it hard work for you? Do you get up in the morning and ...? It's a habit. It's a habit. Hemingway used to say, "The hardest thing to do is pick up a pencil." He's absolutely right. But he said the only hope is for him to have a habit, and he's absolutely right [on that], too. So I treat it like it is a bodily function. I get up about 6 in the morning and I have my shower, read the paper and have the coffee. And by 7:30 or 8, I'm in front of the computer, without a thought. But I don't want it to be a drag, so I do allow myself a degree of freedom. I have four or five things I'm doing at once, and I'm allowed to pick which one I want to do -- what I feel like. If you involve your feelings in your writing, you're lost. You mean if your feelings aren't there? No. If they are there. If they are there? Look at Thomas Wolfe, he's unreadable. Oh, I see, I see. So it's a question of not being overwhelmed by your feelings? Not even to acknowledge it. I don't believe feelings. Feelings are only ideas whose time has not come yet. No, just throw away the feelings. But in the end, the description leads to others feeling. Oh, if it's any good, sure. Okay. If it's any good, that's what it's supposed to do. Okay. So you're really clinical in the act of doing? Yes. But the impact on the reader is different. Yes, it's supposed to be different. What you're doing is communicating the kind of feelings you know well that you have, but you're trying to communicate them in a very cool kind of way, through your writing, through a description which is so precise that the reader will have no recourse but to say, "Yes, that's the way it is." It's interesting, because one of the pieces that I read in this beautiful new book that you have, The Donald Richie Reader, was your description of a stripper, actually. And it was just what you said, very analytical but really sort of left you with the feelings of that experience. I hope so. And its complexity ... "complexity" is not the word, but it captured both the sordidness but also something else, the dimension of the work involved by the participants. If it did that, then it's successful. You say somewhere, in learning about Japan, you learned about yourself. Your childhood positioned you for this. What did you mean by that? Or was that something that you may not have said, but someone wrote about you? And do you agree with that? Oh, I agree about that, not only for myself but for everybody. Yes, I think your childhood does position you. Life is an elimination process. And, eventually you paint yourself in the corner. But in this process of elimination, a lot of things get eliminated when you are young. You do it yourself. I did it myself, certainly. I was unable to play football well. I was unable to eat tomatoes. I was unable to live in Lima. You make these decisions about yourself. I had myself well positioned, and then fate, or whatever circumstance gave me this particular country, which had a number of things in it which satisfied inchoate emotional needs. if I hadn't led an active emotional life in Japan, I probably wouldn't have stayed. I certainly don't want to go down in the annals as being a cold, analytical person. I'm not. I have a very active, inconvenient emotional life. And I found ways in which this country answered it, in a way in which my own country, in no form, did. So this was, again, among the reasons why I stayed. They were not entirely intellectual, of course. People say, "When did you fall in love with Japan?" Well, I don't know that I ever did fall in love with Japan. But down there somewhere is it affected, admitted, a very emotional need, and satisfied it to the extent that I could live there. Let's talk a little about Japan, but before we do that, what do you think young writers should understand about writing? They should understand that it's not a question of inspiration. If they sit around waiting for this, it will never occur. If you're very lucky, the impulse may be strong enough that you can sit down one day and, "Oh look" -- you pull out a whole piece without it falling apart in your hands. But, usually it's like going to the toilet, you know, you have goblets. Or like giving birth -- if you're lucky, the child emerges; otherwise, you've got some mess that you have to patch together. Most writers, myself included, don't get whole roasts out of the oven. What you get is something you can then put together. And one of the skills of the writer is to be able to do this. But the point is that your emotions are not involved directly. You don't wait to be inspired. You don't wait until you feel like it. If you wait until you feel like it, it will never occur. It's a discipline like any other discipline. I mean, why don't people treat it like a sport, or like bodybuilding or something? It is very much like bodybuilding, in that you have a regime, and you submit to it, and it seems dull, and you do the same thing over and over again. But something does come out. Muscle does grow, and you do get larger and fitter, and better. And it does happen. But I think, one should treat one's writing as a habit. Proust said that probably some of the most beautiful passages, ones that take our breath away, were written by a writer with his elbow on the table and his head in his hand, who was using the other one to fan away his yawns as he wrote. And this is probably quite true. There must be a lot of courage involved in both the loneliness, on the one hand, and the chaos that you have to bring order to. Well, bringing order to chaos -- of course, there's nothing more fun than that. That is really a good, cool thing to do. I love to do that. That's why I like to the arrange books and I like to do all sorts of things like that. So that's so much for courage. I don't know about this. I think need has something to do with this. I need to validate myself. I keep journals, and I need them to validate my days, to make them having been worthwhile. I stopped my diaries in '99, and I really miss them because it's as though I'm living out of control. The days go by and I don't even remember what happened. My life had less importance or less self-importance to me, once I stopped the diaries. Boswell says exactly the same thing. He uses those very words. "He must validate the days, or else he feels that he is not alive." What is that process of validation? Is it not just describing and recording, but also interpreting, analyzing, or what? I would think all of those things. Boswell certainly thought so. Of course, he had a grand goal, which was Dr. Johnson. Most of us don't have anything that grand to move toward. But the very fact that you are making a record of your days signifies their worth, I suppose. Japan: Retrospect The story of your writing is really your continuing sojourn in Japan. It turned out to be that way. Japan is such a complicated place, and you have helped introduce it to us in very simple and powerful ways. But what should we be left with? Is that a fair question? Is there some way to summarize those few things that are a simple rendering of your understanding of Japan? It's like a prism. A prism has lots of facets. One of the facets which must concern us now is that Japan has usually been largely misrepresented as being monolithic, as being people all with the same face and the same expression, and the same kind of thoughts. This is not true. I mean, this is true of no people on earth. People are just as variegated in Japan as they are in Brooklyn. But for political purposes, since all countries need to have an "other" to compare themselves, and hence, find themselves, more and more in America, since we have this new infatuation with China, Japan has been used as the "other" -- this mysterious, enigmatic, and so forth and so forth. This is one of the things I think I have to correct. I cannot correct the source of the problem, which is that people usually think that things exist dualistically -- this is something the Greeks gave us. So people think you must either like Bruckner or Mahler -- this is a pair-- or Debussy and Ravel -- that's another pair. It doesn't occur to anybody that these are absolutely discreet things, not to be compared with each other. So it's the same way Japan or China: Orient, right? Japan, China, right? Now, China has ascended because it's got all the money. When Japan was really rich ten years ago, then there was an awful lot of interest in the country. So right now, Japan is a big monolith. It's them. It's the other. It's something against which we can define ourselves. I would like to (and, indeed, I have to some extent done so) show what the country is truly like, and to stop this sort of political nonsense. You have written, "To think of Japan is to think of form. But beneath this, a social pattern also exists. There's a way to pay calls, a way to go shopping, a way to drink tea, a way to arrange flowers, a way to owe money. A formal absolute exists and is aspired to: social form must be satisfied, if social chaos is to be avoided. Though other countries also have certain rituals that give the disordered flux of life a kind of order, here these become an art of behavior." That was true when I wrote it. And it's still true, I'm sure. No. It's not true? No. And why not? My other theme is the great metamorphosis of Japan. Japan is changing, as we speak, to such an extraordinary sense, that the Japan that I wrote about is going to be like the Medes and the Persians in another ten years. Enormous changes are afoot. And so the politesse of which I write is pretty much vanished. The other day I did what I thought had been proper -- I had to pay somebody some money, so I put it in a piece of paper, which is traditionally done -- white paper, and then give them the money. And he laughed. He said, "What are you wasting the paper for?" He got the paper and pulled the money out and put it in his pocket. Ah, gone! There went a whole section of the [culture]. I see a hole, this whole museum disappearing. I thought it would last forever. I subscribed to the theory that the surface may change, but the core holds. Well, the core is not holding. What does that mean for the world, if Japan changes in the way that you're talking about? Oh, we all change. Heraclitus tells us that's what it's about. So it happens. But in the case of Japan, it's very dramatic, because I cannot think of another country which, for well over 150 years, held its former feudal face. That the face is crumbling now is not surprising. It's surprising it didn't crumble 100 years ago. I am going to articulate a point about your work; tell me if I'm right or wrong. I find in your stance toward Japan a Japanese-like quality, which is very much like the way you describe how the Japanese relate to nature and the world, and the reality around it. Is that fair? I'd be surprised if it weren't true, but with the question goes an assumption that this is something which is to be learned exclusively from Japan. This is not true. What I find in Japan is exactly the same thing that I find when I looked out of the window in my pensive elegiac days and was able to discover what I had done. This quality, this refraction of reality, is something which would have concerned me no matter where I went. But it has taken the particular form of the country I'm in. If Henry James had gone to Luxembourg instead of England, it would have been a different set of novels, right? In the same way, if I'd gone to someplace else, the same thing would have operated. But the end product would have looked different because it is, after all, Japan that I live in, and Japan that I describe, so it's not surprising that it's Japanese. I would conclude that your destiny was to wind up in a place like Japan, so that you could both find yourself and effectively use the skills in two different, very important media. I think you could say that, yes. Let me ask you one final question. If students watch this interview, what lessons do you think they might learn from this journey -- from Lima to Tokyo via cinema and writing as an expatriate? I don't know. One of the great things which moved 1915 France was the final line of Les Nourritures Terreste by André Gide, which I might translate as, "Nathaniel, get out! Get out!" I think, maybe, that would be my message to you. On that note, Mr. Richie, thank you very much for joining us today for this Conversation with History. Thank you very much. Thank you. © Copyright 2001, Regents of the University of California