The State of Nature: Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau

advertisement

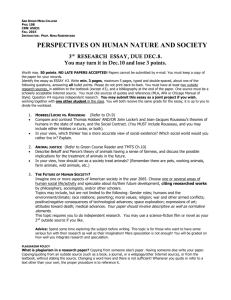

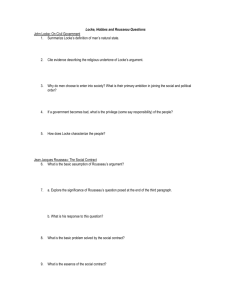

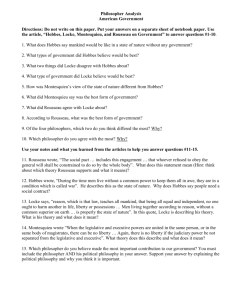

Enlightenment Essay We have been studying the fundamental principles of authority, power, and the ‘Social Contract’. Thomas Hobbes and John Locke have quite different views on the idea of popular sovereignty, natural law, and the social contract. In this essay, you will have the opportunity to select Hobbes or Locke and defend their position as the most effective and ‘natural’ application of these concepts. Your Assignment Write an essay defending the position of Hobbes OR Locke’s views of purpose of the Social Contract and of the role of the laws of nature in their political philosophy. This will take the form of a formal academic essay. Your essay should address the following topics: The similarities and differences between Locke and Hobbes How each writer uses the idea of the ‘Social Contract’ Text Evidence requirement You will use the following sources in your essay. TWO explicit quotes provided in the reading from Hobbes AND Locke. At least ONE quote from Montesquieu or Rousseau that supports or refutes Locke or Hobbes. The following terms must be used within the essay: Power (as defined in the text) Authority (as defined in the text) Legitimacy Natural Law Popular Sovereignty Social Contract These terms must be used correctly in the context of your essay to count as being used! (note – some of these terms are from the last essay. This should be a clue that these are fundamentally important terms for success in this class) The final essay will be typed – you will have one - two periods to plan (computers) and one period to write – using labs or laptops. All text requirements should be identified using BOLD FACE type. If you don’t finish in one period, we will have to collect and grade what you have written in the provided time. YOU MUST USE GOOGLE DOCS TO WRITE YOUR ESSAY AND YOU MUST SHARE THE ESSAY WITH ME. Nlhs.mrhistory@gmail.com is the special email I have created for this purpose. 1 Enlightenment Essay How your essay will be scored: Your essay will be assigned scores for the following components of good writing, which are more specifically outlined on your rubric: 1. Coherence/focus – how clearly state your position/interpretation, how well you maintain your focus, and how fully you respond to the prompt and develop and support your thesis. 2. Organization – how well your ideas logically flow from the introduction to paragraphs to conclusion using effective transitions and how well you stay on topic throughout the essay. 3. Elaboration of evidence – how well you provide evidence from sources about your opinions and elaborate with specific information. (Requirements: minimum of 3 pieces of explicit text evidence) 4. Language and vocabulary – how well you effectively express ideas using precise language that is appropriate for your audience and purpose. (Natural Law, Individual rights, Popular Sovereignty, the social contract, Rule of Law, and Checks and Balances.) 5. Conventions – how well you follow the rules of usage, punctuation, capitalization, and spelling. 2 Enlightenment Essay Analysis Questions: Answer these questions while you read. This will help you organize your essay and possibly take a position if you are struggling to choose a stance. I may be able to provide you with a google form for these questions. Otherwise, you need to create a document to answer them. 1. Why is the basic nature of humans discussed in these excerpts? 2. Why is the topic of human nature important to consider when developing an ideal form of government? 3. What do you believe caused each writer’s opinion on the topic? 4. How could Locke and Hobbes have come to such different conclusions? 5. How do Locke’s and Hobbes’ ideas relate to your own personal experience with people and the role environment plays in forming ideas? 6. Which position does Rousseau seem to support? What evidence do you see to help you make this conclusion? 7. What position does Montesquieu seem to support? What evidence do you see that helps you come to this conclusion? Prep Grade I am grading you on your preparation and execution. You will earn points as follows: Questions A-G Vocabulary terms defined PRIOR to writing the essay and related to one or more of the sources Venn Diagram Points (0-6 points each) 6 terms @ 5 points each 0-42 0-30 2 similarities/2 differences (7 points each) Total possible points 28 (bonus points up to 2 extra) 100 (114 with possible bonus points) 6 = above and beyond; detailed response, referencing quotes or passages from sources. 5 = good evidence, drawing on multiple sources (three or more) 4 = at least one piece of evidence from at least two sources. 3 = question answered, one or more piece of evidence from at least one source. 2 = question answered, no evidence. 1 = inconsistent response 0 = no response 3 Enlightenment Essay The SOURCES a. Background Reading (secondary source) b. Selections from Thomas Hobbes c. Selections from John Locke d. Selections from Jean-Jacque Rousseau e. Selections from Baron du Montesquieu 4 Enlightenment Essay The State of Nature: Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Rousseau Starting in the 1600s, European philosophers began debating the question of who should govern a nation. As the absolute rule of kings weakened, Enlightenment philosophers argued for different forms of democracy. Thomas Hobbes In 1649, a civil war broke out over who would rule England—Parliament or King Charles I. The war ended with the beheading of the king. Shortly after Charles was executed, an English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), wrote Leviathan, a defense of the absolute power of kings. The title of the book referred to a leviathan, a mythological, whale-like sea monster that devoured whole ships. Hobbes likened the leviathan to government, a powerful state created to impose order. Hobbes began Leviathan by describing the “state of nature” where all individuals were naturally equal. Every person was free to do what he or she needed to do to survive. As a result, everyone suffered from “continued fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man [was] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” In the state of nature, there were no laws or anyone to enforce them. The only way out of this situation, Hobbes said, was for individuals to create some supreme power to impose peace on everyone. Hobbes borrowed a concept from English contract law: an implied agreement. Hobbes asserted that the people agreed among themselves to “lay down” their natural rights of equality and freedom and give absolute power to a sovereign. The sovereign, created by the people, might be a person or a group. The sovereign would make and enforce the laws to secure a peaceful society, making life, liberty, and property possible. Hobbes called this agreement the “social contract.” Hobbes believed that a government headed by a king was the best form that the sovereign could take. Placing all power in the hands of a king would mean more resolute and consistent exercise of political authority, Hobbes argued. Hobbes also maintained that the social contract was an agreement only among the people and not between them and their king. Once the people had given absolute power to the king, they had no right to revolt against him. 5 Enlightenment Essay Hobbes warned against the church meddling with the king’s government. He feared religion could become a source of civil war. Thus, he advised that the church become a department of the king’s government, which would closely control all religious affairs. In any conflict between divine and royal law, Hobbes wrote, the individual should obey the king or choose death. But the days of absolute kings were numbered. A new age with fresh ideas was emerging—the European Enlightenment. Enlightenment thinkers wanted to improve human conditions on earth rather than concern themselves with religion and the afterlife. These thinkers valued reason, science, religious tolerance, and what they called “natural rights”— life, liberty, and property. Enlightenment philosophers John Locke, Charles Montesquieu, and JeanJacques Rousseau all developed theories of government in which some or even all the people would govern. These thinkers had a profound effect on the American and French revolutions and the democratic governments that they produced. Locke: The Reluctant Democrat John Locke (1632–1704) was born shortly before the English Civil War. Locke studied science and medicine at Oxford University and became a professor there. He sided with the Protestant Parliament against the Roman Catholic King James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1685. This event reduced the power of the king and made Parliament the major authority in English government. In 1690, Locke published his Two Treatises of Government. He generally agreed with Hobbes about the brutality of the state of nature, which required a social contract to assure peace. But he disagreed with Hobbes on two major points. First, Locke argued that natural rights such as life, liberty, and property existed in the state of nature and could never be taken away or even voluntarily given up by individuals. These rights were “inalienable” (impossible to surrender). Locke also disagreed with Hobbes about the social contract. For him, it was not just an agreement among the people, but between them and the sovereign (preferably a king). According to Locke, the natural rights of individuals limited the power of the king. The king did not hold absolute power, as Hobbes had said, but acted only to enforce and protect the natural rights of the people. If a sovereign violated these rights, the social contract was broken, and the people had the right to revolt and establish a new government. Less than 100 years after 6 Enlightenment Essay Locke wrote his Two Treatises of Government, Thomas Jefferson used his theory in writing the Declaration of Independence. Although Locke spoke out for freedom of thought, speech, and religion, he believed property to be the most important natural right. He declared that owners may do whatever they want with their property as long as they do not invade the rights of others. Government, he said, was mainly necessary to promote the “public good,” that is to protect property and encourage commerce and little else. “Govern lightly,” Locke said. Locke favored a representative government such as the English Parliament, which had a hereditary House of Lords and an elected House of Commons. But he wanted representatives to be only men of property and business. Consequently, only adult male property owners should have the right to vote. Locke was reluctant to allow the propertyless masses of people to participate in government because he believed that they were unfit. The supreme authority of government, Locke said, should reside in the lawmaking legislature, like England’s Parliament. The executive (prime minister) and courts would be creations of the legislature and under its authority. Montesquieu: The Balanced Democrat When Charles Montesquieu (1689–1755) was born, France was ruled by an absolute king, Louis XIV. Montesquieu was born into a noble family and educated in the law. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, including England, where he studied the Parliament. In 1722, he wrote a book, ridiculing the reign of Louis XIV and the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church. Montesquieu published his greatest work, The Spirit of the Laws, in 1748. Unlike Hobbes and Locke, Montesquieu believed that in the state of nature individuals were so fearful that they avoided violence and war. The need for food, Montesquieu said, caused the timid humans to associate with others and seek to live in a society. “As soon as man enters into a state of society,” Montesquieu wrote, “he loses the sense of his weakness, equality ceases, and then commences the state of war.” Montesquieu did not describe a social contract as such. But he said that the state of war among individuals and nations led to human laws and government. Montesquieu wrote that the main purpose of government is to maintain law and order, political liberty, and the property of the individual. Montesquieu opposed the absolute monarchy of his home country and favored the English system as the best model of government. 7 Enlightenment Essay Montesquieu somewhat misinterpreted how political power was actually exercised in England. When he wrote The Spirit of the Laws, power was concentrated pretty much in Parliament, the national legislature. Montesquieu thought he saw a separation and balancing of the powers of government in England. Montesquieu viewed the English king as exercising executive power balanced by the law-making Parliament, which was itself divided into the House of Lords and the House of Commons, each checking the other. Then, the executive and legislative branches were still further balanced by an independent court system. Montesquieu concluded that the best form of government was one in which the legislative, executive, and judicial powers were separate and kept each other in check to prevent any branch from becoming too powerful. He believed that uniting these powers, as in the monarchy of Louis XIV, would lead to despotism. While Montesquieu’s separation of powers theory did not accurately describe the government of England, Americans later adopted it as the foundation of the U.S. Constitution. Rousseau: The Extreme Democrat Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) was born in Geneva, Switzerland, where all adult male citizens could vote for a representative government. Rousseau traveled in France and Italy, educating himself. In 1751, he won an essay contest. His fresh view that man was naturally good and was corrupted by society made him a celebrity in the French salons where artists, scientists, and writers gathered to discuss the latest ideas. A few years later he published another essay in which he described savages in a state of nature as free, equal, peaceful, and happy. When people began to claim ownership of property, Rousseau argued, inequality, murder, and war resulted. According to Rousseau, the powerful rich stole the land belonging to everyone and fooled the common people into accepting them as rulers. Rousseau concluded that the social contract was not a willing agreement, as Hobbes, Locke, and Montesquieu had believed, but a fraud against the people committed by the rich. In 1762, Rousseau published his most important work on political theory, The Social Contract. His opening line is still striking today: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Rousseau agreed with Locke that the individual should never be forced to give up his or her natural rights to a king. 8 Enlightenment Essay The problem in the state of nature, Rousseau said, was to find a way to protect everyone’s life, liberty, and property while each person remained free. Rousseau’s solution was for people to enter into a social contract. They would give up all their rights, not to a king, but to “the whole community,” all the people. He called all the people the “sovereign,” a term used by Hobbes to mainly refer to a king. The people then exercised their “general will” to make laws for the “public good.” Rousseau argued that the general will of the people could not be decided by elected representatives. He believed in a direct democracy in which everyone voted to express the general will and to make the laws of the land. Rousseau had in mind a democracy on a small scale, a city-state like his native Geneva. In Rousseau’s democracy, anyone who disobeyed the general will of the people “will be forced to be free.” He believed that citizens must obey the laws or be forced to do so as long as they remained a resident of the state. This is a “civil state,” Rousseau says, where security, justice, liberty, and property are protected and enjoyed by all. All political power, according to Rousseau, must reside with the people, exercising their general will. There can be no separation of powers, as Montesquieu proposed. The people, meeting together, will deliberate individually on laws and then by majority vote find the general will. Rousseau’s general will was later embodied in the words “We the people . . .” at the beginning of the U.S. Constitution. Rousseau was rather vague on the mechanics of how his democracy would work. There would be a government of sorts, entrusted with administering the general will. But it would be composed of “mere officials” who got their orders from the people. Rousseau believed that religion divided and weakened the state. “It is impossible to live in peace with people you think are damned,” he said. He favored a “civil religion” that accepted God, but concentrated on the sacredness of the social contract. Rousseau realized that democracy as he envisioned it would be hard to maintain. He warned, “As soon as any man says of the affairs of the State, ‘What does it matter to me?’ the State may be given up for lost.” 9 Enlightenment Essay Primary Sources Source 1: SELECTIONS FROM THE LEVIATHAN Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) Human Equality: Nature has made men so equal, in the faculties of the body and mind; as that though there be found one man sometimes manifestly stronger in body, or of quicker mind than another, yet when all is reckoned together, the difference between man and man, is not so considerable. . . For such is the nature of men, that howsoever they may acknowledge many others to be more witty, or more eloquent, or more learned; yet they will hardly believe there be many so wise as themselves. . . . The State of Nature: From this equality of ability, arises equality of hope in the attaining of our ends. And therefore if any two men desire the same thing, which nevertheless they cannot both enjoy, they become enemies. . . . Hereby it is manifest, that during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war, as is of every man, against every man. For war consists not in battle only, or the act of fighting, but in a tract of time, wherein the will to contend by battle is sufficiently known. In such condition there is no place for industry [meaning productive labor, not industry in modern sense of factories], because the fruit thereof is uncertain, and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building . . . no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and, which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short. 10 Enlightenment Essay Source 2: SELECTIONS FROM OF CIVIL GOVERNMENT John Locke (1632-1704) The State of Nature To understand political power aright, we must consider what state all men are naturally in, and that is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature; without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man. . . The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions: for men [are] all the workmanship of one omnipotent and infinitely wise Maker; all the servants of one sovereign master, sent into the world by his order, and about his business. . . . Reason Men living together according to reason, without a common superior on earth, with authority to judge between them, is properly the state of nature. God, who hath given the world to men in common, hath also given them reason to make use of it to the best advantage of life, and convenience. The earth, and all that is therein, is given to men for the support and comfort of their being. Nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy. And thus, considering the plenty of natural provision there was a long time in the world, and the few spenders . . . there could be then little room for quarrels or contentions about property so established. 11 Enlightenment Essay Rousseau (1712 – 1788) Origin and Terms of the Social Contract Man was born free, but everywhere he is in chains. This man believes that he is the master of others, and still he is more of a slave than they are. How did that transformation take place? I don't know. How may the restraints on man become legitimate? I do believe I can answer that question.... At a point in the state of nature when the obstacles to human preservation have become greater than each individual with his own strength can cope with . . ., an adequate combination of forces must be the result of men coming together. Still, each man's power and freedom are his main means of self-preservation. How is he to put them under the control of others without damaging himself . . . ? This question might be rephrased: "How is a method of associating to be found which will defend and protect-using the power of all-the person and property of each member and still enable each member of the group to obey only himself and to remain as free as before?" This is the fundamental problem; the social contract offers a solution to it. The very scope of the action dictates the terms of this contract and renders the least modification of them inadmissible, something making them null and void. Thus, although perhaps they have never been stated in so man) words, they are the same everywhere and tacitly conceded and recognized everywhere. And so it follows that each individual immediately recovers hi primitive rights and natural liberties whenever any violation of the social contract occurs and thereby loses the contractual freedom for which he renounced them. The social contract's terms, when they are well understood, can be reduced to a single stipulation: the individual member alienates himself totally to the whole community together with all his rights. This is first because conditions will be the same for everyone when each individual gives himself totally, and secondly, because no one will be tempted to make that condition of shared equality worse for other men.... Individual Wills and the General Will In reality, each individual may have one particular will as a man that is different from-or contrary to-the general will which he has as a citizen. His own particular interest may suggest other things to him than the common interest does. His separate, naturally independent existence may make him imagine that what he owes to the common cause is an incidental contribution - a contribution which will cost him more to give than their failure to receive it would harm the others. Whatever benefits he had in the state of nature but lost in the civil state, a man gains 12 Enlightenment Essay more than enough new ones to make up for them. His capabilities are put to good use and developed; his ideas are enriched, his sentiments made more noble, and his soul elevated to the extent that-if the abuses in this new condition did not often degrade him to a condition lower than the one he left behind-he would have to keep blessing this happy moment which snatched him away from his previous state and which made an intelligent being and a man out of a stupid and very limited animal.... 13 Enlightenment Essay Baron de Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755) The Spirit of the Laws 1748 In every government there are three sorts of power; the legislative; the executive, in respect to things dependent on the law of nations; and the executive, in regard to things that depend on the civil law. By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws, and amends or abrogates those that have been already enacted. By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies; establishes the public security, and provides against invasions. By the third, he punishes criminals, or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other simply the executive power of the state. The political liberty of the subject is a tranquility of mind, arising from the opinion each person has of his safety. In order to have this liberty, it is requisite the government be so constituted as one man need not be afraid of` another. When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may anse, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner. Again, there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor. There would be an end of every thing were the same man, or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people to exercise those three powers that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and that of judging the crimes or differences of individuals. Most kingdoms in Europe enjoy a moderate government, because the prince, who is invested with the two first powers, leaves the third to his subjects. In Turkey, where these three powers are united in the sultan's person the subjects groan under the weight of a most frightful oppression. In the republics of Italy, where these three powers are united, there is less liberty than in our monarchies. Hence their government is obliged to have recourse to as violent methods for its support, as even that of the Turks witness the state inquisitors, and the lion's mouth into which every informer may at all hours throw his written accusations. 14 Enlightenment Essay Thomas Hobbes V. John Locke Organizer. Directions: Use the Venn diagram to compare and contrast the similarities and differences between the ideas of John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. Don’t forget their different views of the Social Contract. You should be able to find at least 2 similarities and 2 differences. Hobbes 15 Locke