Secondary source quotation integrated into essay.

advertisement

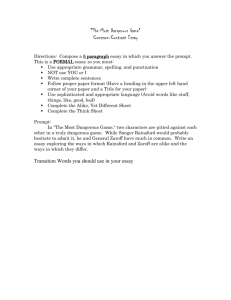

Integrating Sources - use quotations as support, not in key places like thesis or topic sentences - mention details about the source where appropriate - vary use of direct quotation and paraphrase - choose quotations carefully, quote accurately, and integrate smoothly - authors “write”; characters/narrators “say” as you read, always be on the lookout for useful quotations highlight annotate Primary source quotation integrated into essay. By the same token, Borges believes that a person’s life is at the transition complete mercy of the person who is living it. As Dr. Yu Tsun speaks to Albert, the duo discuss the notion of parallel dimensions in time, where a single decision can take on multiple consequences. Albert reasons that “all verb: “reasons” possible outcomes occur; each one is the point of departure for other forkings” (578). As a person who is anti-fatalist, Albert demonstrates how characters in Tsun’s ancestor’s book can choose different paths leading to very different lives. In this way, Albert is essentially commenting on how a person’s life is essentially composed of decisions resembling forking paths that bring one unique results. According to Albert, “Time forks perpetually toward innumerable futures” (579). The passage of time leads the characters in the novel or people in life towards different paths that define them as a person and mark their lives. Tragedy can affect a person, but if one takes a different path, one can always find a vastly different situation on the basis of one decision. Thus, Borges feels that life is a series of decisions as opposed to a series of points, and that life is at the hands of not a higher being and destiny, but in the hands of the human being. “thus” concludes argument Primary source quotation integrated into essay. Upon hearing his daughter’s first attempt at telling “a simple story […] the kind de Mauppasant wrote, or Chekov,” the father becomes obviously disappointed as the eight sentence, choppy tale she recites is void of descriptive elements he feels are necessary to any good story (471). For the father, a narrative stripped of these adjectives makes it unworthy of the title of “story.” To prove his point, he launches into a series of questions designed to enhance his daughter’s otherwise drab tale. The father asks, “Her looks for instance […] Her hair? […] What were her parents like, her stock? […] What about the boy’s father. Why didn’t you mention him? Who was he? Or was the boy born out of wedlock?” (472). It is firstly important to note how the father urges his daughter to emulate the Russian writers he so loves. That they are all male writers of psychological realism is of no consequence, pointing towards the more conservative taste of the father. It is also interesting to note how the father’s requirements of a good story can be viewed. His questions pertain to appearance, family background/ethnicity, and marital status, hinting to the father’s conservative, traditional views of women in society. These descriptors indicate that, for the father, a conventional approach to basic ingredients in a story qualifies it as good literature. quote as part of sentence Primary source quotation integrated into essay. In addition to being very linear, the story also has a tragic ending. At the very end of the story Rainsford and Zaroff have one final conflict. At this very clear paragraph topic sentence; note transition point, Rainsford has already defeated Zaroff and has beaten him in his sick game, yet Rainsford still pushes the game on further. Both characters square off and Zaroff says, “one of us is to furnish a repast for the hounds. The other will sleep in this very excellent bed” (Connell 492). It was appropriate verbs: says Rainsford who had decided that “he had never slept in a better bed” (Connell 492). What this statement reveals is that a shift has occurred in Rainsford. Rainsford is no longer an innocent man caught in the dilemma of whether to commentary follow directly from quotation participate in Zaroff’s sick game or to face the general’s henchman, Ivan, who will tear him apart. Rainsford is now a murderer who extended the game and may very well become the new master of the island. This tragic transformation of Rainsford into a killer fits very well with the father’s belief that stories should end in tragedy. notice movement from topic to specific detail and back to topic paragraph concludes on same topic; and link to general essay thesis Joyce Carol Oates’ story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?,” was written as fiction; however, it was actually inspired by a headline in the news. In his essay, “Oates as Writer,” Tom Quirk states, “Oates’s character [...] was derived from the exploits, widely publicized by Time, Life, and Newsweek magazines during the winter of 1965-66, of a real killer from Tucson, Arizona” (227). The character to which Quirk refers becomes more and more relevant as the story progresses. Secondary source quotation integrated into essay. name primary author and text transition with “however” to show logical relationship introduce quote with info about secondary source and author quote is short and to the point (notice part omitted) MLA citation correct quote is “surrounded” by the student’s own commentary Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” tells the tale of a young Puritan man, Goodman Brown. The Puritan religion heavily influenced the story. As Michael E. McCabe writes, “Hawthorne sets ‘Young Goodman Brown’ into a context of Puritan rigidity and self-doubt to allow his contemporary readers to see the consequences of such a system of belief” (43). The story begins as Goodman Brown leaves his wife, Faith, to begin his journey into a forest. It seems that even before leaving, he realizes that his adventure into the forest will involve evil, suggesting very early the Puritan self-doubt that McCabe identifies: “Poor little Faith!” thought he, for his heart smote him. “What a wretch am I, to leave her on such an errand! She talks of dreams too. Methought, as she spoke, there was trouble in her face, as if a dream had warned her what work is to be done tonight.” (164) secondary sources supports the argument (it doesn’t make it) plot details accompanied by analysis secondary source referred to as the argument develops In the forest he is confronted by a man older than himself. Although Brown was mildly surprised by the stranger’s presence, we are told that he (the stranger) was not wholly unexpected. As the two men walk through the forest, it becomes apparent that the person Goodman Brown walks with is an evil figure, and perhaps more importantly, the townspeople have some form of alliance with him. For example, in the scene where they confront the woman who taught Brown his “catechism,” she admits to worshipping the stranger, and even mentions a sort of initiation, like a baptism. With this knowledge, Brown attempts to reject the traveler. Unfortunately, as they walk he becomes more and more doubtful and he sees more familiar faces in the dark forest. Joan D. Winslow summarizes this encounter in her essay, “Brown and Temptation,” when she writes, “During their conversation Brown’s reluctance to proceed onward is gradually overcome by the stranger’s assertions and demonstrations that those people Brown has always believed virtuous are journeying toward the meeting in the forest” (238). parenthetical remark keeps the pronouns clear “more importantly” as a rhythmic but also rhetorical device “for example” as transition source as support “summarizes”; “this encounter” functions as transition (a linking strategy) Quotations integrated into essay Borges uses the opening frame in "The Garden of Forking Paths" to draw a distinction between Hart's quantitative style of history and Yu Tsun's experiential account of the war. Yu Tsun's final statement in the story is, "He [detective Richard Madden] does not know (no one can know) my innumerable contrition and weariness" (580). Instead of attempting to recount the war in quantitative terms through dates, numbers and death tolls, Yu Tsun captures the human side, the savage side, through his subjective and emotional confession. Borges uses the following selected passage of Hart's history in "The Garden of Forking Paths" as the opening frame of the story: One page 22 of Liddell Hart's History of World War I you will read that an attack against the Serre-Montauban line by thirteen British divisions (supported by 1,400 artillery pieces), planned for the 24th of July, 1916, had to be postponed until the morning of the 29th. The torrential rains, Captain Liddell Hart comments, caused this delay, an insignificant one, to be sure. (573) Hart's description of the event is vastly different than Yu Tsun's. Robert Chibka, in his essay, "The Library of Forking Paths," comments that, "Liddell Hart's delay is 'insignificant' not to a soldier trapped in a flooded trench but to the scholar whose magisterial view cannot afford to accommodate the emotional bewilderment that comes to Yu Tsun" (141). Borges uses Hart's passage because it represents the simplistic lens through which we view history. In reality, history happened many different ways to many different people. History can never be completely recreated because, as Yu Tsun states, "Everything that happens to a man happens precisely, precisely now" (573). Borges, through contrasting these two perspectives on history, shows that to limit oneself to a single idea of how history occurred is not prudent. clear topic [ ] clarify supporting evidence Signal Verbs/Phrases (do not always use “writes that” or “says that”) Be careful in literature essays that the signal verb makes sense; for example, “Wordsworth observes that “Five long years have past” in his poem “Tintern Abbey” (line 1), makes more sense than “Wordsworth argues that “Five long years have past” in his poem “Tintern Abbey” (line 1).” according to argues suggests observes asserts claims states comments contends concludes emphasizes replies agrees concurs responds offers disagrees remarks endorses reasons adds admits confirms illustrates acknowledges rejects agrees implies reports insists notes believes points out