Welcome to Life's Levels Of Grief

advertisement

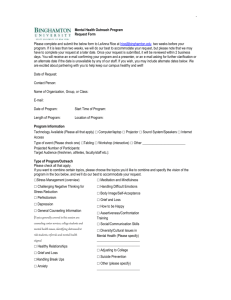

UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Presented by Dr. Susan R. Rose March 2, 2011 UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Introductions Your name Your title and your school/organization Educational Goals What brought you to this session? To the conference? Something of interest about yourself that you haven’t already mentioned Favorite vacation Hobbies Foreign languages UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Purpose of Grief …this is not a process which can be rushed. It is about integrating the changed circumstances into the survivor’s ongoing life. Related Quotes & Thoughts While I thought I was learning how to live, I was learning how to die. - Leonardo da Vinci Life is measured not by its length, but by its depth. – Mary Fisher UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 1: Defining the Loss Experiences That Generate Grief Reactions Grief knits two hearts in closer bonds than happiness ever can; and common sufferings are far stronger links than common joys. -Alphonse de Lamartine (French writer, poet, and politician, 1790-1869) School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education The Experience of Loss Bereavement: The objective event of loss Disrupts survivor’s life “Shorn off or torn up” / “Being robbed” A normal event in human experience Grief: The Reaction to Loss Thoughts (mental distress) Feelings (emotions) Physical responses Behavioral responses Spiritual responses Mourning Process by which a bereaved person integrates a loss into his or her ongoing life Determined partly by social and cultural norms for expressing grief UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Basic Facts about Loss and Grief Every year, two million people die in the U. S. Chronic illnesses such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes account for two of every three deaths. These illnesses create many losses before death is anticipated. Accidents are the leading cause of death children under age eighteen. Accidents are also the cause of many disabling injuries, creating loss of mobility, fine motor skills, and cognitive functions. In 1999, the most recent year for which statistics are published by the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 568,000 children were removed from their biological families to live in foster care. These children, their biological and foster parents, siblings, teachers, and counselors/social workers are all affected by loss and grief. If each of these deaths affects just five people, at least ten million people are affected each year. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Basic Facts about Loss and Grief cont. According to predictions based on the U.S. census, approximately 43% of marriages in the U.S. will end in divorce. Some parents and children who experience divorce consider adjusting to the losses associated with it to be as challenging as the losses associated with death. The tragic events of September 11, 2001 immediately affected people all over the world. Traumatic losses associated with these terrorist attacks, along with other tragedies such as the Columbine High School shootings, have an impact on individuals and communities far beyond what can currently be understood. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education If you’re wondering what you should gain from this workshop, you should ask yourself: How comfortable and confident am I in my own ability to deal with grief and loss? How well do I understand the impact of death on people of different ages, genders, cultures and spiritual orientations? How familiar am I with other life events and losses that can cause grief reactions? Am I confident that I can identify when an individual or family is expressing normal grief or when their grief may be complicated? How prepared am I to respond effectively to those around me who are grieving? Do I know how to acknowledge grief and make a referral to an appropriate resource when necessary? School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands More Insight into the Purpose of this Workshop The Keeper http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Symbolic (Psychological) Loss Divorce/The end of a relationship without one of the partners dying Foster care placement Children leaving home for independent living (The “empty nest”) Unemployment or Job demotion Changes in health status Moving, Selling a childhood home, etc. Parents whose children have been diagnosed with a disabling medical or mental condition Moving parents into a nursing home Loss of independence Miscarriage/Infertility Death of a pet School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Loss and Grief in Different Contexts Crisis Counseling We can’t “cure” grief, but we can offer help and care. Trauma Therapy/Counseling Becoming attuned to grief issues helps identify and assist with loss and grief associated with these problems. Unacknowledged Grief – For example: Losing a parent symbolically due to substance abuse Refugees fleeing their homeland Empty Nest (High School Counseling) Loss of Health School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Loss and Grief in Different Contexts cont. The “Tough” Kid 14-year-old girl place in therapeutic home for adolescents Mother died in a car accident when she was a toddler Father was incarcerated at the time, so she and her sister were moved from family member to family member as well as to foster homes where she was sexually and physically abused. Frequent expression of anger and poor behavior resulted in residential placement, outside of the city in which she has spent her childhood and separate from her sister. What do you think happened next? School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Small Group Exercise (3 – 4 members) Divide a sheet of paper into two columns. In the first column, write down the types of losses, both actual and symbolic, that students are likely to experience. In the second column, write the emotions someone experiencing each loss is likely to experience. Discuss your thoughts about how you might observe these losses and the feelings related to them. (For example, a school counselor leading a group for children whose parents are divorcing might observe academic problems with some of the children.) School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Share out in Large Group Although the world is full of suffering, it is full also of the overcoming of it. - Helen Keller School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 2: Self-Preparation - Preparing Yourself to Help Others Encountering Loss and Grief Everything that happens to you is your teacher. The secret is to sit at the feet of your own life and be taught by it. Polly B. Berends (Author & Editor of Children’s book) - What is of greatest importance in a person’s life is not just the nature and extent of his or her experiences but what has been learned from them. -Norman Cousins School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Reviewing Our Own Experiences and Attitudes Related to Grief Experiences with death or loss significantly influence the way we react to the losses of other, both consciously and unconsciously. Take a few moments now to think about the following questions. What was your earliest experience with death or loss? How old were you when it occurred? Where were you when you learned of the loss? Who did it involve? What were the physical, emotional, and cognitive reactions you were aware of in yourself following the loss? How did the people around you respond to the loss? How did they respond to your reactions? How did your cultural and/or spiritual background influence your responses? What about the loss makes you feel vulnerable now? Based on what you have learned since, what do you think can help you to cope more easily with death or loss now and in the future? How do you think your own feelings and reactions to loss may impact your work with others who are experiencing loss or trauma? School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Assessing and Enhancing Readiness to Address Grief in Our Work How do we know if we are ready to help others with their grief? Self-Assessment/Self-Awareness Working with individuals and families facing loss inevitably brings up emotions and memories for every professional. Establishing competence in providing care to those who are grieving. Support clients in their expression of emotional needs Actively listen Refer to support groups, peer support programs, and professional experts Ask open-ended questions such as, “How are you doing?” School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Supervision, Consultation, and Collaboration with other Professionals Especially important when exposure to distress of others is prolonged, frequent, or intense. Vicarious/Secondary trauma: a common reaction in professionals who work closely with individuals or groups who directly experienced trauma. Supervisors, peers and consultants can help us to recognize when our own reactions may be distressed. Interdisciplinary/Multidisciplinary Team Counselors Teachers Attendance Specialists/Clerks Disciplinary Staff Administrative Personnel School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Questions, Comments, Concerns UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Childhood Factors that influence a child’s a child’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions to death: Chronological age Earlier experiences with death Reactions of adults and other children around them Child’s own unique personality and coping style School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Infants Key developmental issues for infants are dependency and attachment. Developmental Factors Understanding of death Reactions to loss What can help? Dependence on caregivers for all basic needs Limited object constancy – the understanding that person or object exists, even if not physically present. Limited ability to verbalize. Few coping strategies to regulate tension. Do not recognize Experience feelings of loss in reaction to separation that are part of developing an awareness of death Emotional: Sluggish, quiet, unresponsive to a smile or a coo; may also cry and appear inconsolable Physical: Weight loss, less active, sleep less Maintaining normal routines of care giving and familiar surroundings Providing a consistent caregiver who can give frequent and lengthy periods of love and attention, including holding and hugging Providing consistent, gentle, physical and verbal reassurance and comfort Expressing confidence in the child and the world School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Ages 2 – 3 (Toddlers) Like infants, key developmental issues for toddlers are dependency and attachment. Great variation in cognitive and emotional development Developmental Factors Understanding of death Reactions to loss What can help? Ambivalence about independence Increasing comprehension and articulation of language Learning by mimicking and following the examples of others Generally cannot cognitively understand death Cannot differentiate absence for a short time from a long time Can sense loss of change but often cannot verbally explain or discuss it Emotional: Express discomfort or insecurity through frequent crying or protest; Express distress or sadness through withdrawal, loss of interest in usual activities, and changes in eating and sleeping patterns. Physical: May show regression through clinging or screaming when a caregiver tries to leave; May express distress through regression, often giving up previously acquired skills such as speaking clearly, toileting, and self-soothing at bedtime Same as infant + Providing simple, understandable verbal explanations for changes Naming feelings expressed by the child and those the child observes being expressed by others, such as, “Daddy feels sad; that is why he is crying.” School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Ages 3 - 6 Children at this stage are still thinking concretely and may perceive death as a kind of sleep Department of Education Concept of death may involve magical thinking Developmental Factors Developing a fuller mastery of language Learning to read Expressing feelings through art and play Acquiring social skills through interactions and observing others Understanding of death Reactions to loss What can help? Cannot quite comprehend the difference between life and death Emotional: May be very anxious that something could happen to them or someone else upon whom they are dependent; May exhibit searching behaviors Physical: May have trouble eating, sleeping, and controlling bladder and bowel functions Explaining death in simple and direct terms, including only as much detail as the child is able to understand. Answering a child’s questions honestly and directly, making sure that the child understands the explanations provided. Reassuring children about their own security and explaining that they will continue to be loved and cared for (They often worry that their surviving parent or caregiver will go away) Encouraging master of age appropriate skills while allowing for regression Expressing confidence in the child and the world. School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Ages 6 – 9 Children in this age are commonly curious about death and may ask questions about what happens to one’s body when a person dies. Children beginning in this age benefit from being invited to contribute to memorial ceremonies or activities. Developmental Factors Relationships with peers and adults are important Striving for mastery of information and tasks Superego and a sense of responsibility are developing Cognitively, they are still thinking concretely. Understanding of death Reactions to loss What can help? Children’s questions often indicate their efforts to understand death fully. Can become afraid of going to school or have difficulty concentrating, may behave aggressively, become overly concerned about their own health, or withdraw from others. Discussions of death that include proper words, such as ‘died” and ‘death” Providing opportunities for children to ask questions freely and to express their feelings directly or through creative activities Providing reassurances that the child’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior did not cause death Reading aloud stories or books that deal with death and allowing the child to share their reactions or questions Inviting children to share memories and participate in ceremonies or remembrance activities School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education The Sandpiper http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education What is your Joy? School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Ages 9 – 12 Child is developing an increasing grasp of abstract concepts By the time a child is 12, death is seen as final and something that happens to everyone Developmental Factors Interest in and capacity to understand biological processes Heightened sensitivity to others’ emotions Increased awareness of vulnerability Regressive and impulsive behaviors indicate stress Understanding of death Reactions to loss What can help? Death is usually known to be unavoidable and is not seen as punishment Greater risk for symptoms of depression, withdrawal, anxiety, conduct problems, changes in school performance, and low self-esteem Capable of empathy Talking about death can help children learn effective ways to cope with loss Providing an opportunity to explore and discuss spiritual and cultural beliefs related to loss Providing physical outlets for strong emotions Encouraging expression of feelings through different media including art, music, dance, and writing. Letting children know they are not alone and that others experience loss and the feelings related to it. Modeling direct and constructive expression of feelings naturally associated with loss such as anger and sadness. School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Adolescence Adolescents may view death in the family as making them appear different from their peers May perceive death has placed greater demands on their own development Developmental Factors Searching for identity Peer relationships are very important Exposure to maladaptive responses to stress Abstract thinking Understanding of death Reactions to loss Adolescents comprehend that death is permanent, irreversible, and affects everyone. At risk for exposure to maladaptive coping strategies; May also be at risk for parentification What can help? Talking openly about death, indicating that the subject is not off-limits Verbal or written explanations that tears, sadness, anger, guilt, and confusion are all part of normal grief Providing opportunities for adolescents to hear from and talk with peers who have also experience loss Inviting the adolescent to help plan or participate in memorial or remembrance activities in the way that feels most comfortable to them Connecting adolescents to peers who have similar experiences to reduce isolation Encouraging journal writing or using other methods to express thoughts and feelings Constructing memorials, memory books, boxes, or quilts, or providing other tangible ways to memorialize significant relationships School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Young Adulthood Multiple demands of life may deter ability to devote time and energy to grief. Developmental Factors Expected to be self-sufficient (economically, if not emotionally) Developing career and life plans Expanding their range of roles and coping strategies Understanding of death Fully comprehend and are also capable of comprehending the complex range of responses of different people to different types of losses Reactions to loss What can help? Vulnerable to the emergence of anxiety, depression, and other disorders that stress related to loss can exacerbate Acknowledge the multiple impacts of loss and the normalcy of grief reactions Encouraging individuals to take time to attend to their own feelings as well as those of others Acknowledging or providing opportunities for expression and discussion of conflicting feelings Promoting social connections through peer support and group activities Referring young adults to credible Internet sources for information and peer support School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Middle Adulthood “Sandwich” generation Developmental Factors Re-examination, renewal, and /or reintegration of identity Multiple roles and responsibilities Long-established patterns may be difficult to change Increased vulnerability to physical disorders Reactions to loss What can help? “Pile-up” of losses Maladaptive patterns may make the process of grieving complicated Empathic listening and support Release time from work or school to meet family obligations and process grief Bereavement support groups Tangible expressions of support or caring Pastoral care or connection with a religious or spiritual community Identification of risk factors and offering intervention for complicated grief Opportunities for respite and renewal Opportunities to assist others School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Late Adulthood Textbooks define this as 65 and older Developmental Factors Reactions to loss What can help? Poor health or disabling medical conditions may have significant impact as biological aging progresses Serenity and wisdom may be sought Changes in identity related to work and family occur Adaptation to changes in information processing and memory is required to maintain maximum functioning Multiple losses require continuing adaptation; May be difficult to differentiate between grief and depression Acknowledgement of symbolic losses as well as losses through death Maintaining or augmenting social supports Provision of income supports or economic assistance, when needed Identifying new activities, roles, and relationships to augment or replace those that have been lost Conducting informal and formal life review, with emphasis on strengths and contributions School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Conducting informal and formal life review, with emphasis on strengths and contributions A Life Well-Lived http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Advanced Age Textbooks define this as 80 and older Developmental Factors Vulnerability to social isolation, disabling medical conditions, and memory loss Adaptation to multiple losses, both symbolic and through deaths Change in sense of time A sense of consummation and conclusion in life Reactions to loss Anticipate own death; Reminiscence is common and often brings a positive sense of closure and fulfillment School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Advanced Age cont. What can help? Reminiscence through sharing of memories, with individuals and groups “Make memories, Little Buddy, because when you get older, that’s all you’ll have.” Thank You for Your Time , http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Advanced Age – What can help? cont. What can help? Reminiscence through sharing of memories, with individuals and groups Providing concrete supports to allow expenditures of time and energy on satisfying activities and relationship (helping with household maintenance or bill paying) Acknowledging losses as well as strengths and coping capacities Encouraging completion of advance directives Providing opportunities to open discuss ideas, values, feelings, and fear related to dying and death Just Be There School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Just Be There http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Questions, Comments, Concerns UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 4: Normal and Complicated Grief Reactions School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education And can it be that in a world so full and busy the loss of one creature makes a void in any heart so wide and deep that nothing but the width and depth of eternity can fill it up! - Charles Dickens School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Theories That Inform Our Understanding of Grief Sigmund Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia (1917) John Bowlby elaborated on Freud’s ideas (1973) Every human infant develops attachments to significant people (whom he referred to as “objects”) through the process of Cathexis. Cathexis: process of attaching emotionally Decathexis: process of letting go of an attachment as an adaptive response to loss of a significant “object” Proposed that attachment behavior helps infants establish an maintain a sense of security throughout their life. According to Bowlby’s theory, grief reaction of the bereaved to the loss of a significant other is a similar process. Bereaved must cease investing their emotional energy (referred to as libido in both Freud and Bowlby) in the deceased in order to reinvest it in other relatioship Both believed that with the passage of time grieving individuals could achieve decathexis Failure to do this results in depression School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Theories That Inform Our Understanding of Grief Eric Lindemann became interested in grief reactions after a major tragedy in Boston, the Coconut Grove nightclub fire, took the lives of 492 people in November 1942. Lindeman studied the grieving survivors and found common reactions of: Physical or Bodily Distress Preoccupations with the image of the person who had died Anger or hostility Guilt Impaired functioning in work or family roles He also identified task that grievers completed that resulted in a diminishment of these symptoms. Acknowledging the reality of the death Adjusting to life without the deceased person Forming new relationships School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Theories That Inform Our Understanding of Grief Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, a physician who worked with dying patients, made major contributions to our understanding of Anticipatory Grief. Pioneering Publications in the 1960’s and 1970’s described her stage model 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Denial and Isolation Bargaining Anger Sadness/Depression Acceptance Parkes (1998) identified related stages in the grieving process Shock or numbness Yearning and pining (anger & guilt) Disorganisation Beginning to pull life back together School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Theories That Inform Our Understanding of Grief More recently, grief counselors Therese Rando and William Worden have expanded on earlier theories Worden (2005) concentrates on tasks of grieving that have to be worked through (‘grief work’) if resolution of grief is to take place: To accept the reality of the loss To work through or experience the pain of grief To adjust to a changed environment in which the deceased is missing To emotionally relocate the deceased and move on with life and capacity to love others. Rando’s 6 R’s/ The Tasks of Mourning Recognize the loss React to the separation Recollect the deceased and the relationship Relinquish old attachments to the deceased Readjust adaptively into a new world without forgetting the old Reinvest University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Common Reactions in Normal Grief Highly variable and individualistic Grief reactions vary across a wide spectrum according to: Cultural Backgrounds Social Support Networks Gender Socioeconomic Status Psychological Health Circumstances of Loss Complex, evolving process Multiple dimensions Signs of grief may appear immediately after the death or may be delayed or even absent No predetermined timetable for “completion” Most often, the social and emotional support provided by family and friends is enough School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Normal Grieving Behaviors Thoughts (Mental Distress) Confusion, inability to concentrate or remember details, disbelief, anxiety; Sense of disorganization; Depression; Sensory responses undependable and erratic; and auditory or visual experiences that mimic hallucinations – such as seeing an image of the deceased person or hearing their voice – are not uncommon following a loss Feelings (Emotions) Physical (Somatic) Sensations Sadness, Longing, Loneliness, Sorrow and Anguish, Guilt, Frustration at being unable to control events, Anger and outrage at injustice of the loss, Anxiety, Fatigue, Helplessness, Numbness, Shock, and even Relief Tightness in the chest or throat, choking, shortness of breath; Lack of energy; Feeling of emptiness in the abdomen and stomach; Frequent sighing; Sleep disruptions (e.g., insomnia); Changes in appetite; Chills, tremors, hyperactivity Behavioral Responses Crying; Searching for the deceased; Incessant talk about the deceased and circumstances of death; Avoidance of talk about the deceased; Restlessness, irritability, hostility School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Expressions of Mourning The bereaved are “different” for a time Abstaining from social occasions Visual Symbols Black armbands National flag at half-mast Seclusion Cutting long hair short (Native Americans) University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education The Course of Grief (Summarizing Normal Grief) Initial phase: Shock, numbness, disbelief, denial Middle phase: Anxiety, despair, volatile emotions, yearning for deceased, feelings of abandonment Last phase: Sense of resolution, reintegration, and transformation; turmoil subsides; balance regained University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Complicated Grief Complicated Grief/Complicated Mourning: difficulty coping with loss; prolonged distress long after the loss has occurred. Failure to complete the tasks of grief/mourning results in several types of complicated mourning: Delayed grief: when a loss is insufficiently mourned Masked grief: when grief is absent immediately after a loss but appears later in the form of a medical or psychiatric problem Exaggerated grief: when a normal grief reaction, such as depressed mood or anxiousness, goes beyond normal grief to a clinical level of depression or anxiety Chronic grief: when the mourner is stuck, sometimes for many years, in the grief process Anomic grief: where there is an absence of standards or guidance on how to grieve. The person does not know what to do, doesn’t know how to deal with the loss, change in circumstances. Forbidden grief: when others deny the person has suffered any loss. Time-limited grief: the idea is that you should get back to normal, especially emotional normality, as soon as possible. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Who is at risk for complicated grief? Perceived lack of social support High Profile Losses Examples: Execution of a prisoner, loss associated with AIDS, death of a drunk driver, suicide Unique losses that produce intense grief reactions for a long time Reduced income or unexpected financial debt Loss of important roles Loss of a job or health insurance Disenfranchised loss: losses accompanied by stigma resulting in loss of support or acknowledgment for grieving survivors Lack of privacy; frequent inquiries about and exposure to the details of the loss make it difficult to obtain respite Multiple Stressors Examples: Suicide, older adults who have already sustained the loss of many members of their primary support network, Children placed in foster care Examples: Loss of a child, Parents whose children have been removed by CPS or how have relinquished the role of parent through adoption Sudden, unanticipated loss (especially when traumatic, violent, mutilating, or random) Bereaved’s perception that the death was preventable Death from overly lengthy illness Relationship that was markedly angry, ambivalent, or dependent Mental health problems or unaccommodated losses School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Danger of “Medicalizing” Grief Because circumstances and personalities differ, what is a pathological response for one mourner may be an appropriate response for another mourner Many of the criteria suggested for making a diagnosis of traumatic grief appear virtually indistinguishable from the signs of normal grief Label of “dysfunctionality” may be applied to normal expressions of grief and mourning. No direct cause-effect link established between bereavement and onset of disease. Higher incidence of some chronic diseases in recently bereaved individuals Mortality/Morbidity of Grief: Studies Reported... Diminished immune response has been found among widowers during first months following bereavement Death rate during first year of bereavement nearly seven times that of general population (small community in Wales) University UC of the Cumberlands Variables Influencing Grief Survivor’s model of the world Personality Cultural context and social roles Perceived relationship with the deceased Values and beliefs Mode of death Anticipated Sudden Suicide Homicide Disaster Multiple losses and bereavement burnout Social support and disenfranchised grief Unfinished business Department of Education UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Interventions for Normal and Complicated Grief Why and how can a referral to a mental health professional or grief therapist help? According to the DSM-IV, bereavement is considered to be complicated by a major depressive episode if the normal depressive symptoms are accompanied by: Morbid preoccupation with worthlessness, suicidal ideation Marked functional impairment or psychomotor retardation of prolonged duration School Counseling Program UC University of the Department of Education Cumberlands Interventions for Normal and Complicated Grief Preventive Interventions Anticipatory grieving Education Emotional support Monitoring, with social support Support groups Face-to-face Online Telephone (Skype, etc.) School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Interventions for Normal and Complicated Grief Maintaining Bonds Rather than severing ties with the deceased, the bereaved person incorporates the loss of a loved one into his or her ongoing life Maintain “inner representation” of the deceased Bonds sustained through memories and linking objects The “ties that bind” are maintained by “threads of connectedness” UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Interventions for Normal and Complicated Grief cont. Brief supportive or bereavement counseling Grief therapy Psychiatric referral and use of psychotropic medication Innovative Interventions Individual Couples Family Therapy Daylong workshops Annual memorial workshops held at hospitals or hospices Retreat programs/Camp Programs Bibliotherapy Using music in counseling School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Exercise: Identifying Signs of Normal and Complicated Grief Think of someone you know who has experienced a loss. Using the normal emotions of grief as a checklist, note whether the person showed signs of sadness, anger or guilt that are a part of normal grief. Describe your observations Discuss whether you saw signs of complicated grief. Describe the type of complicated grief the individual evidenced and the interventions that may have been helpful to them to complete the tasks of grieving. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Share out in Large Group Only people who avoid love avoid grief. The point is to learn from it and remain vulnerable to love. - John Brantner School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Cultural and Spiritual Influences We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope. - Martin Luther King, Jr. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Grief and Loss Grief and loss can be said to be part of every human life although the meaning of this experience and responses to it are unique. Each of us will grieve in our own unique way for the unique loss that we have suffered. There is no right or wrong way to grieve. Each person’s unique feelings of grief and loss will be influenced by the culture and society in which they live. University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education Influence of Culture in Coping with Loss and Grief Culture: the integrated pattern of human that includes thoughts, communications, actions, beliefs, values, and institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious, or social group. Often referred to as the totality of ways that are passed down from one generation to another (NASW, 2005) Cultural Sensitivity: an awareness of, and appreciation for, the differences in values, beliefs, and norms of people from different cultural and spiritual backgrounds. Cultural Competence: professionals practice of cultural sensitivity as well as the ability to engage and interact effectively with people from diverse cultural backgrounds. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Lack of Awareness of different cultural groups’ responses can lead us to: Misinterpret an individual’s or family’s reactions Fail to offer support or assistance that might be perceived as helpful Offend the grieving person(s) and create a barrier to their receiving care and support School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Group vs. the Individual Knowledge of a particular group does not necessarily equip someone to adequately understand in individual, who may not subscribe to the beliefs or norms of the group. Differing Spiritual Practices within the group Differing Norms based on: Socioeconomic Status Multiple Group Memberships Individual Ideology Sharing Stories of Differing Cultural Experiences School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Gender and Grief In American culture, men are taught not to show emotions such as sadness, loneliness, or depression. Causes some men to be unable to cope with the feelings they are experiencing. They may not have health outlets to express their emotions School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education The Transmission of Cultural Messages Family communication or interaction Mass Media Vicarious Experiences Makes us all “Instantaneous” survivors Contributes to “Grief Denying” culture Famous are front page news, while the average Joe or Jill is buried in death notices deep in “Section G” School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education The Transmission of Cultural Messages Culture of Poverty and Violence “Waking up and living another day, facing an endless accumulation of losses” Area where much work is needed Let’s Brainstorm School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Influence of Spirituality in Coping with Loss and Grief Spirituality: that which gives meaning to one’s life and draws one to transcend oneself Expressions of Spirituality Prayer Meditation Interactions with others or nature Relationship with God or a higher power Religion: communal or institutional expression or practice of faith. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Assessing importance of Spirituality in People’s Lives Pulchalski (1999) developed a user tool: F: Faith or beliefs I: Importance and influence C: Community A: Address School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Exercise 1. Of the stories that we discussed earlier or other experiences that you have had, discuss the funeral rituals or mourning behavior you have observed. 2. What aspects of these rituals are similar to the practices of your own cultural or religious groups? 3. What aspects are different? 4. Of the rituals, practices or behaviors you have observed in your own life, which ones do you feel would be particularly helpful for those who have experienced a loss? School Counseling Program UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Share out in Large Group While we are mourning the loss of our friend, others are rejoicing to meet him behind the veil. ~John Taylor School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 6: Counseling the Individual What Can We Do To Help? One of the most beautiful compensations of this life is that no man can sincerely try to help another without helping himself. - Ralph Waldo Emerson School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Grief “No one ever told me that grief felt so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering, the same restlessness, yawning. I keep on swallowing. At other times it feels like being mildly drunk, or concussed. There is a sort of invisible blanket between the world and me. I find it hard to take in what anyone says. Or perhaps, hard to want to take it in; it is so uninteresting. Yet I want the others to be about me. I dread the moments when the house is empty. If only they would talk to one another and not to me” C.S. Lewis, A Grief Observed UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Misconceptions of Grief 1. Time heals all wounds. 2. People find it too painful to talk about their loss. 3. Crying indicates that someone is not coping well. 4. The grieving process should last about one year. 5. Quickly putting grieving behind will speed the process of healing. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Empathic Communication Active Listening S= Sit up straight L= Lean forward (Attentive body language) A= Activate your thinking N= Note key ideas (Verbal following) T= Track the talker (Appropriate eye contact) Communication Facilitation Reflection of feeling Paraphrasing Use of minimal encouragers Use of open-ended questions Therapeutic silence School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Empathic Communication Avoid: Saying “I know how you feel” or “I understand.” Talking about your own losses (me-too-ism) Parroting or repeating the speaker’s exact words. Try, instead to respond to the actual content expressed. Thinking about or planning your own responses instead of listening to what is being said. Giving unsolicited advice. Breaking silences too quickly or filling in before the speaker has finished speaking. Challenging the other person’s perception of their situation or feelings. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Utilizing Information and Resources Identify key experts in your own community and obtain their contact information Internet National Organizations Compassionate Friends: support organization for parents who have lost a child COPS (Concerns of Police Survivors): organization assisting survivors of police who die in the line of duty The Dougy Center: National Center for Grieving Children and Families Cancer Care KET: Kentucky Educational Television Examples: Before It’s Too Late – Preventing Teen Suicide, http: www.ket.org/health/before-its-too-late.htm ; The Forgetting - A Portrait of Alzheimers, http://www.ket.org/forgetting/ PBS: Public Broadcasting System School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Collaborating with Others Core functions related to goal attainment: Completing a thorough assessment Contributing to the development of a comprehensive educational/treatment plan Participating as a member of the interdisciplinary team Implementing the components of the educational/treatment plan Evaluating progress Advocating School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Functions of Team Members Counselors contribute an understanding of: Counselors help other professionals cope effectively with the demands of their work. Compassion Fatigue: the reactions that professional caregivers sometimes experience in the process of helping others with grief, loss, and trauma. Secondary trauma/Vicarious trauma: trauma that professional caregivers can experience through listening to the details of trauma that others have experienced. Expressing feelings to others who can listen empathetically and provide support Using stress management techniques Making sure there is a balance in our lives School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Books About Death, Loss, Illness, and Hope for Children and their Caregivers http://www.counselingtoday.com/ FreeStuff.html UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Songs about Grief http://www.recover-fromgrief.com/songs-about-grief.html UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Visual Art & Grief Materials Paper: Letter, Legal, Butcher, Bulletin Board, etc. Colorful Copy Paper Construction Paper Ribbon Yarn Glue Sticks and/or Tape Coloring Pencils and/or Crayons Pencils and/Pens (Depending on age) Any other Art supplies you have on hand Beads, glitter, sequins, etc. UC University Department of Education of the Cumberlands Grief Box Your Grief Box for Counseling Books CD’s with songs Visual Art supplies Student’s Grief Box Decorated Cardboard Box (Shoe Box, Shirt Box, etc.) Hand-made frames (Child can place pictures later) Quotes, Phrases, Scripture verses, etc. Journal (Notebook tied together with ribbon will suffice) Any other memories UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Questions , Comments, Concerns UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 7: When Organizations and Communities Grieve As the sun illuminates the moon and stars so let us illuminate each other. - Master Lui School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Counselors can make a significant difference through a variety of helpful responses: Practicing empathic communication (Chapter 6) Referring a client to a support group, a bereavement counselor, or another community provider (Chapter 4) Attending a funeral or planning a memorial service can serve as an expression of support Offering to be present with those who are grieving Taking a Leadership Role School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Establishing a Bereavement Protocol: Interdisciplinary Collaboration Communicate the news to all the members of the school community who knew the deceased. 2. Provide concrete ways for people to express their caring and concern. 3. Acknowledge the loss in meetings and classes. 4. Obtain consultation or support for staff who are providing grief counseling to others, if needed. 1. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Creating Remembrances and Memorials Memorial cookbook for an avid cook Memorial Walk accompanied by a “Concrete” Memorial Honorary Trees/Bushes Donate organs as a “living” tribute Foundations to collect $ to find a cure for a disease that took the loved one Scholarships or Memorial funds Memorial Events Basketball Games, Dances, etc. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only that ever has. Department of Education Discuss the Charles Schulz Philosophy - Margaret Mead http://www.counselingtoday.com/FreeStuff.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Questions , Comments, Concerns UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Level 8: Self-Care – Sustaining Hope, Helpfulness, and Competence in Working with Grief Look well into thyself. There is a source of strength which will always spring up if thou will always look there. - Marcus Aurelius Antoninus School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Continuing Education You have taken the first step in taking care of yourself. You are here! School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Self-Care Strategies Avoid compassion fatigue Take regular time off Vacation Mental health days Creative Expressions Art Music Dance Peer Support Debriefing Supervisor who can balance employee’s need for empathy and protection with the need to feel competent and to continue work School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Informal Self-Care Strategies Department of Education Spend more time with family and friends Enjoy evenings full of laughter, ice cream and good times Exercise regularly Write a journal Eat healthy food Take a bubble bath Take time for appreciating or creating art Watch a sunset Read for leisure Gardening Yoga (active relaxation) School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Informal Self-Care Strategies Hug someone Listen to music (singing along with the radio in the car works wonders) Watch movies (Save the heavy dramas for when life isn’t already full of dramas) Go for a walk Dance Get a good night’s sleep Eat one piece of chocolate Reduce clutter/Get more organized so that the details of everyday life don’t add to stress Take a weekend retreat or a day trip Take a vacation School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Informal Self-Care Strategies Listen to soft music in combination with deep breathing exercises Listen to a guided imagery tape Meditate Take at least 1 – 2 hours every week to do something you want to do Get a massage Begin the day with gratitude and continue to practice it throughout the day Practice mindfulness Pray Enjoy the Ride: http://www.lshs64.com/enjoytheride.html School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Professional Support Systems Seeking help for ourselves Warning signs that trigger that we need to seek help: Use of maladaptive strategies Overworking Avoiding others Using substances Shutting down our emotions Options for Self-Care Same organizations and resources we provide to clients Same methods of individual or group counseling we use with clients Trusted supervisor or colleague can help with referral Effective models of Professional Development Retreats for Professionals coping with grief School Counseling Program University UC of the Cumberlands Department of Education One Last Thing We need to take a proactive role in preventing burnout and managing stress related to professional caregiving. Philosophy for Old Age http://www.authorstream.com/Presentation/aSGuest40 411-347103-philosophyforoldage-entertainment-pptpowerpoint/ School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Exercise Ask yourself the following questions: Why am I drawn to the work I do? 2. What feelings are you aware of as you think about more in-depth work with others experiencing grief? 3. What plans do you have to sustain yourself in your work with grieving clients in the future? What strategies and methods to you plan to use personally to prevent burnout and compassion and fatigue, and to maintain a balance in your personal and professional life? 1. School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Share out in Large Group There are things that we don't want to happen but have to accept, things we don't want to know but have to learn, and people we can't live without but have to let go. ~Author Unknown School Counseling Program UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Questions , Comments, Concerns UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education CURRENT, UPDATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Adams-Greenly, M. and Moynihan, R.T. (1983). Helping the children of fatally parents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 53, 219-229. Aguilera, D.C. (1998). Crisis intervention. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year. Albom, Mitch. (2002). Tuesdays with Morrie: An old man, a young man, and life’s greatest lesson. New York, NY: Random House. Allen, J. (2002). Using literature to help troubled teenagers cope with end-of-life issues. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. Barnes, G.E. and Prosen, H. (1985). Parent death and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 64-69. Becvar, D. (2001). In the presence of grief. New York, NY: Guildford. Bendikson, R. and Fulton, R. (1975). Childhood bereavement and later behavioral disorders. Psychiatric Annals, 16, 276-280. Benner, D.G. (1991). Counseling as a spiritual process. Oxford, UK: Clinical Theology Association. Biegel, D.E., Sales, E., and Schulz, R. (1991). Family caregiving in chronic illness: Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, heart disease, mental illness and stroke. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Boyd-Webb, N. (2002). Helping Bereaved Children, 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Guildford. Bragdon, E. (1990). The call of spiritual emergency: From personal crisis to personal transformation. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row. Brock, S.E., Lazarus, P.J. and Jimerson, S.R. (Eds.) (2002). Best practice in school crisis prevention and intervention. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologist. Brunhofer, M.O. (1997). Mourning and loss: A life cycle perspective. In J.R. Brandell (Ed.), Theory and Practice in Clinical Social Work. (pp. 662-688). New York, NY: The Free Press. Burke, M.T. & Miranti, J.G. (Eds.) (1995). Counseling: The spiritual dimension. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. Corr, C.A. and McNeil, J.N. (1986). Adolescence and death. New York, NY: Pergammon Press. Doka, K.J. (1989). Disenfranchised grief: recognizing hidden sorrow. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. Doka, K. and Davidson, J. (1998). Living with grief: Who we are and how we grieve. Philadephia, PA: Taylor Francis. Eliade, M. (1987). The Encyclopedia of Religion. New York, NY: MacMillan Press. Ernswiler, J. and Ernswiler, M. (2000). Guiding your child through grief. New York, NY: Bantam/Random House. Freeman, S.J. (2005). Grief and loss: Understanding the journey. Belmont, CA: Thomson, Brooks/Cole. Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. Standard Edition, 14: 237-258. London: Hogarth Press. Gilbert, K.R. (1996). “We’ve had the same loss, why don’t we have the same grief?: Loss and differential grief in families. Death Studies, 20, 269-283. Gluhoski, V.L. (1995). A cognitive perspective on bereavement: Mechanism and treatment. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, (9)2, 75-84. International Work Group on Death, Dying, and Bereavement. (1992). "A Statement of Assumptions and Principles Concerning Education about Death, Dying, and Bereavement." Death Studies, 16:59–65. Worden, W. (2001). Children and Grief, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guildford. UC University of the Cumberlands Department of Education Irish, D.P., Lundquist, K.F., and Nelson, V.J. (1993). Ethnic variations in Dying, Death and Grief. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis. James, R. and Gilliland, B. (2005). Crisis Intervention Strategies. 5th Ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Jamison, K.R. (1999). Night falls fast: Understanding suicide. New York, NY: Knopf. Johnson, C.J. and McGee, M.G. (Eds.). (2002). How different religions view death and afterlife. Philadelphia, PA: The Charles Press. Johnson, S.W. and Maile, L.J. (1987). Suicide and the schools: A handbook for prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation. Springfield, IL: Thomas Press. Kamerman, J.B. (1988). Death in the midst of life: Social and cultural influences on death, grief and mourning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall. Lindemann, E. (1944). The symptomatology and management of acute grief. American Journal of psychiatry, 101, 141-148. Matsunami, K. (1998). International handbook of funeral customs. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. McGovern, M. and Barry, M. (2000). Death education: Knowledge, attitudes, and perspectives of Irish parents and teachers. Death Studies, 24(4), 325-333. Parkes, M. Loringani, C. and Young, B. (1997). Death and bereavement across cultures. New York, NY: Routlage. Rando, T.A. (1984). Grief, dying and death: Clinical interventions for caregivers. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Rando, T.A. (1993). Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Rothschild, Babette. (2000). The Body Remembers. New York, NY: W.W. Norton Publishing Rowling, L. (2003). Grief in school communities: Effective support strategies. Philadelphia, PA: Open University. Shapiro, E. (1996). Grief as a family process. New York, NY: Guildford. Silverman, P. (2000). Never too young to know. New York, NY: Oxford Press. Soricelli, J. and Utech, C.L. (1985). Mourning the death of a child: The family and group process. Social Work, 30, 429-434. Sprang, G. and McNeil, J. (1995). The many faces of bereavement: The nature and treatment of natural, traumatic, and stigmatized grief. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. Stroebe, M. and Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 197224. Stroebe, M., Gergen, K., and Stroebe, W. (1992). Broken hearts or broken bonds: Love and death in historical perspective. American Psychologist, 37, 1205-1212. Valeriote, S and Fine, M. (1987). Bereavement following the death of a child: Implications for family therapy. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal, 9, 209-217. Volkan, V.D. and Zind, E. (1993). Life after loss: The lessons of grief. New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing Co. Walker, R. and Pomeroy, E. (1996). Depression or grief? The experience of caregivers of people with dementia. Health and Social Work, 21 , 247-254. Walsh, F. and McGoldrick, M. (Eds.). (1991). Living beyond loss. New York, NY: W.W. Norton. Webb, N.B. (2002). Helping bereaved children: A handbook for practioners. New York, NY: Guildford Press.