Measuring the level of economic activity: gross - Learning

advertisement

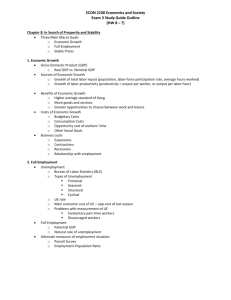

Measuring the performance of the economy Macroeconomic objectives How is the economy performing? What are our economic prospects? Are things going to improve and, if so, when? Why are certain economies doing so well while others are struggling? In order to answer these questions, economists usually distinguish five macroeconomic objectives which can be used to judge the performance of the economy… 1. economic growth 2. full employment 3. price stability 4. balance of payments stability (or external stability) 5. equitable distribution of income Measuring the level of economic activity: gross domestic product The first step in measuring economic growth is to determine a country’s total production of goods and services in a specific period. The central concept in the national accounts is the gross domestic product (GDP). Gross domestic product (GDP): the total value of all final goods and services produced within the boundaries of a country in a particular period (usually one year). At first glance it seems to be a clear and simple concept, but how do the national accountants succeed in adding up all the different types of economic activity in the country during a particular period? To explain this, we have to examine the various elements of the definition of GDP. The first important element is value. The best way to determine value is to use the prices of the various goods and services to obtain the value of production. Once the production of each good or service is expressed in rand and cents, the total value of production can be determined by adding the different values together. The second important element is the word final. One of the major problems that national accountants have to deal with is the problem of double counting. If they are not careful they can easily overestimate or inflate the value of GDP by counting certain items more than once. Consider the following simple example… A farmer produces 1000 bags of wheat which he sells to a miller at R10 per bag, yielding a total of R10 000. The miller processes the wheat into flour, which he then sells to a baker for R12 500. After baking bread with the flour, the baker sells it to a shop for R18 000. The shop subsequently sells the bread to final consumers for R21 000. © Bishops Economics Department Page 1 What is the total value of these four transactions? R61 500? NO! The total value of the farmer’s production cannot be added to the total value of the miller’s sales to the baker, since the value of the production of the wheat is included in the value of the flour sold by the miller. The same applies to the value of the bread. To avoid the problem of double counting, national accountants start with the full value of the farmer’s production and then subsequently add only the value added by each of the other participants in the production process. Nowadays GDP is often also called gross value added (GVA). But what has all this got to do with the adjective final in the definition of GDP? In our example the value of the shop’s sales to the final consumers also amounts to R21 000. The fact that this is exactly equal to the total value added is no accident. Double counting can also be avoided by counting only the value of those sales where a good or service reaches its final destination. Such sales involve final goods and services which have to be distinguished from intermediate goods and services. Any good or service that is purchased for reselling or processing is regarded as an intermediate good or service. Intermediate goods and services do not form part of GDP. Note, however, that it is the ultimate use of a product which determines whether it is a final or an intermediate product. If the flour in the above example is bought by consumers, it would be classified as a final good. There is another way in which double counting can be avoided. That is by considering only the incomes earned during the various stages of the production process by the owners of the factors of production. In our example… R10 000 is earned during the farming stage R2 500 (R12 500 minus R10 000) during the milling stage R5 500 (R18 000 minus R12 500) during the baking stage and R3 000 (R21 000 minus R18 000) during the final selling stage. This again yields a total of R21 000 (R10 000 + R2 500 + R5 500 + R3 000). Note that the income earned during each stage of the production process is equal to the value added during that stage. This is also no accident. Income is earned by producing, that is, by adding © Bishops Economics Department Page 2 value to goods and services. For the economy as a whole, income can be increased only if production increases (ie if more value is added). The fact that value added, spending on final goods and income all yield the same answer means that there are three different ways of calculating GDP. The three methods of calculating GDP illustrated in the example are… 1. the production method (value added) 2. the expenditure method (final goods and services) 3. the income method (incomes of the factors of production) Why do they yield the same answer? The value of final goods and services must necessarily be made up of the successive values added in the different stages of production. In addition, production and income may be viewed as two sides of the same coin. Production is the source of income – the only way in which income can be generated in an economy is by producing (and selling) goods and services. The income earned by the various factors of production (labour, capital, natural resources and entrepreneurship) consists of wages and salaries, interest, rent and profit. Total value of production = combined value of wages and salaries, interest, rent and profit. The three methods essentially measure the same thing, albeit at different points in the circular flow. Further aspects of the definition of GDP Two elements of GDP have now been explained: the meaning of value and the meaning of final goods and services. Two further aspects need to be highlighted… “within the boundaries of a country” - GDP is a geographic concept that includes all the production within the geographic area of a country. This is what is signified by the term domestic in gross domestic product. We shall return to this aspect when other measures of economic activity are discussed. The last important aspect to note is that only goods and services produced during a particular period are included in GDP. GDP therefore concerns the production of new goods and services. GDP reflects only production which occurred during the period in question. Also note that GDP is a flow which can be measured only over a period of time (usually one year). Because production and income are two sides of the same coin. This means that income can be substituted for the product in GDP. Gross domestic product is therefore the same as gross domestic income. The final element of GDP that needs explaining is the word gross. The description of total output as gross product means that no provision has been made for that part of a country’s capital equipment (buildings, roads, machinery, tools, etc) which is ‘used up’ in the production process. © Bishops Economics Department Page 3 Measurement at market prices, basic prices and factor cost (or income) The three methods of calculating GDP will yield the same result only if the same set of prices is used in all the calculations. There are, however, three sets of prices that can be used to calculate GDP… market prices basic prices factor cost (or factor income) In practice… market prices are used when calculating GDP according to the expenditure method basic prices are used when the production (or value added) method is applied factor cost (or factor income) is used when the income method is used. Different valuations of GDP will thus yield different results and you should therefore always check at which prices GDP is expressed. The differences between market prices, basic prices and factor cost (or factor income) are due to various taxes and subsidies on goods and services. When there are indirect taxes (ie taxes on production and products) or subsidies (on production or products) the amount paid for a good or service differs from both the cost of production and the income earned by the relevant factors of production. For example, the amount paid by a consumer for a packet of cigarettes is much higher than the combined income earned by the merchant, the manufacturer, the workers, the tobacco farmer and everyone else involved in the process of producing and selling the packet of cigarettes. The difference is the result of excise duty and value-added tax (VAT), which together constitute almost 50 per cent of the market price of a packet of cigarettes in South Africa. Indirect taxes (i.e. taxes on production and products) thus have the effect of making the market prices of goods and services higher than their basic prices or factor cost. Subsidies have just the opposite effect. They result in market prices being lower than basic prices or factor cost. The national accountants distinguish between two types of tax and subsidy on production and products… taxes/subsidies on products other taxes/subsidies on production. Taxes on products refer to taxes which are payable per unit of some good or service (eg value added tax, taxes and duties on imports and taxes on exports). Other taxes on production refer to taxes on production that are not linked to specific goods or services (eg payroll taxes, recurring taxes on land, buildings or other structures and business and professional licenses). Subsidies on products include direct subsidies payable per unit exported to encourage exports, and product-linked subsidies on products used domestically. Other subsidies on production refer to subsidies that are not linked to specific goods or services (eg subsidies on employment or the payroll). © Bishops Economics Department Page 4 The following identities apply: GDP at market prices - taxes on products + subsidies on products = GDP at basic prices GDP at basic prices - other taxes on production + other subsidies on production = GDP at factor cost (or factor income) Likewise: GDP at factor cost + other taxes on production - other subsidies on production = GDP at basic prices GDP at basic prices + taxes on products - subsidies on products = GDP at market prices Measurement at current prices and at constant prices Another important distinction that needs to be made is that between GDP at current prices (or nominal GDP) and GDP at constant prices (or real GDP). For example, when they calculated the GDP for 2010, the national accountants had to use the prices paid for the various goods and services in 2010. We call this measurement at current prices or in nominal terms (see Box 2-1). However, we are not interested only in the size of GDP during a particular period. We also want to know what happened to GDP from one period to the next. We want to know, for example, how the 2010 GDP compared with the GDP for 2009. This is how we measure economic growth. But in a world in which prices tend to increase from one period to the next (i.e. a world of inflation), it makes little sense to simply compare monetary values between different years. We have to allow for the fact that prices may have increased. For example, in 2010 the South African GDP at current market prices was 11,1% higher than in 2009. But this did not mean that the actual production of goods and services was 11,1% greater in 2010 than in 2009. The largest part of this increase simply reflected the fact that most prices were higher in 2010 than in 2009. To solve this problem, national accountants convert GDP at current prices to GDP at constant prices (or real GDP). This is done by valuing all the goods and services produced each year in terms of the prices ruling in a certain year, called the base year. At the time of writing, 2005 was the base year used by Stats SA and the SARB. In other words, each year’s GDP was also expressed at 2005 prices. This is what we mean when we talk about GDP at constant prices or real GDP. Once this adjustment had been made, the national accountants found that the South African GDP was 2,8% greater in 2010 than in 2009. The growth in GDP at constant prices (or real GDP) was therefore only 2,8%. The difference between this rate and the 11,1% growth in GDP at current prices (or nominal GDP) was the result of price increases (i.e. inflation). © Bishops Economics Department Page 5 Other measures of production, income and expenditure While GDP is undoubtedly the most widely used barometer of total production in an economy in a particular year, the other measures also have specific uses. Gross national income or gross national product The D in GDP represents domestic. It indicates that we are dealing with what occurred within the boundaries of the country. It does not matter who produces the goods or who owns the factors of production. But economists also want to know what happens to the income earned and the standard of living of all South African citizens or permanent residents in the country. To answer this question, all income earned by foreign-owned factors of production in South Africa has to be subtracted from GDP. In addition, all income earned by South African factors of production in the rest of the world also has to be taken into account. To derive GNI from GDP the following must therefore be done: Subtract from GDP o all profits, interest and other income from domestic investment which accrue to residents of other countries o all wages and salaries of foreign workers engaged in domestic production (eg the wages earned by residents of Lesotho, Mozambique and Malawi on the South African gold mines). Add to GDP o all profits, interest and other income from investments abroad which accrue to permanent residents o all wages and salaries earned by permanent residents outside South Africa © Bishops Economics Department Page 6 GNI = GDP + primary income receipts – primary income payments or (since payments are larger) GNI = GDP – net primary income payments to the rest of the world where net primary income payments = primary income payments – primary income receipts) Expenditure on GDP As we learnt previously, there are three approaches to calculating GDP… 1. the production approach (which measures the value added by all the partĪcipants in the economy) 2. the income approach (which measures the income received by the different factors of production) 3. expenditure approach (which measures the spending on final goods and services by the different partĪcipants). With the expenditure approach, the national accountants add together the spending of the four major sectors of the economy: households, firms, government and the foreign sector. Thus, the elements of total spending are… o consumption expenditure by households (C) o investment spending (or capital formation) by firms (I) o government spending (G) o expenditure on exports (X) minus expenditure on imports (M) GDP = C + I + G + (X – M) In the South African economy, final consumption expenditure by households is the largest single element of total expenditure. Gross domestic expenditure (GDE) Expenditure on GDP is always equal to GDP at market prices. It indicates the total value of spending on goods and services produced in the country. However, it does not indicate the total value of spending within the borders of the country. Part of the expenditure on South African GDP occurs in the rest of the world, while part of the spending in the country is on goods and services produced in the rest of the world. The three central domestic expenditure items (C, I and G) do not distinguish between goods and services manufactured locally and those manufactured in the rest of the world (such as French wine, Italian shoes, Japanese CD players and German machinery). These three items constitute gross domestic expenditure (GDE). Economists are particularly interested in GDE, which indicates the total value of spending within the borders of the country. It includes imports but excludes exports, since spending on exports occurs in the rest of the world. GDE = C + I + G o GDE includes imports (M) and excludes exports (X), GDP = C + I + G + (X – Z) o GDP includes exports (X) and excludes imports (Z). © Bishops Economics Department Page 7 If GDP > GDE then exports > imports during that period. o If the value of production in the domestic economy exceeded the value of spending within the country it follows that the value of exports was greater than the value of imports. Conversely, if GDE > GDP, it follows that M > X. Summary o Gross domestic expenditure (GDE) consists of expenditure on final goods and services by households (C), firms (I) and government (G) during a particular period. o GDE includes spending on imported goods and services (M) and excludes exports (X). o GDE is expressed at market prices. o GDE = C + I + G (C, I and G include imported goods and services) From GDE to gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices, o imports have to be subtracted from GDE and exports added. o GDP at market prices = GDE + X – Z o =C+I+G+X–Z From GDP at market prices to gross national income (GNI) at market prices… o net primary income payments to the rest of the world have to be subtracted from GDP o GNI at market prices = GDP at market prices – net primary income payments This information is also summarised in table form on the next page for your convenience. You need to know it well as it is a very popular matric examination question. © Bishops Economics Department Page 8 THE THREE METHODS OF CALCULATING GDP (YOU MUST KNOW THIS TABLE!) Gross Domestic Product Income Approach Compensation to employees + Net operating surplus + Consumption of fixed capital (provision for depreciation) Gross value added at factor cost + Taxes on production - Subsidies on production = Gross value added at basic prices + Taxes on products - Subsidies on products Gross Domestic Product Production Approach Primary sector Agriculture, forestry and fishing Mining and quarrying + Secondary sector Manufacturing Electricity, gas and water Construction + Tertiary sector Wholesale and retail trade, catering and accommodation Transport, storage and communication Financial intermediation insurance, real estate and business services Community, social and personal services Central government services Gross Domestic Product Expenditure Approach C Consumption expenditure by households + G Expenditure by government + I Gross fixed capital formation and changes in inventories (Gross fixed formation capital - Changes in inventories) + = X Z Residual item (errors &omissions) Gross domestic expenditure (GDE) Exports of goods and nonfactor services Imports of goods and nonfactor services = = + = Gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices Primary income from the rest of the world Primary income to the rest of the world Gross national product (GNP) at market prices Gross value added at basic prices + Taxes on products - Subsidies on products = = + = Gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices Primary income from the rest of the world Primary income to the rest of the world Gross national product (GNP) at market prices = + = Expenditure on gross domestic product (GDP) at market prices Primary income from the rest of the world Primary income to the rest of the world Gross national product (GNP) at market prices - Consumption of fixed capital - Consumption of fixed capital - Consumption of fixed capital = Net national product (NNP) at market prices = Net national product (NNP) at market prices = Net national product (NNP) at market prices Amplification of elements contained in the table: Consumption expenditure by households: largest single element of total expenditure in the economy. Gross capital formation: additions to the country’s capital stock with no provision made for the consumption of fixed capital. Gross fixed capital formation: purchase of capital goods like buildings, machinery and equipment. © Bishops Economics Department Page 9 Changes in inventories: goods produced during the period that have not been sold, or goods produced in an earlier period but sold only during the current period. Expenditure by government: this does not include capital expenditure (i.e. investment) as this is included in gross capital formation. Residual item: serves to balance the national accounts when the three methods do not yield exactly the same answer. © Bishops Economics Department Page 10 Measuring employment and unemployment Unemployment: how many people are willing and able to work but do not have jobs at a specific moment in time. Expressed as a percentage of the total number of people who are willing and able to work. This percentage is called the unemployment rate. Problems with this measurement… When exactly is a person employed? What about part-time or seasonal workers? Are housewives employed or unemployed? What about someone who does not have a job but is also not actively seeking work? What about people who are making a living by selling things on the pavement or from illegal activities like prostitution and dealing in drugs? Strict definition of unemployment: a person has to have taken steps recently to find work. Expanded definition of unemployment: the mere desire to find employment is sufficient. Irrespective of which definition is used, unemployment in South Africa is very high and is undoubtedly the most important and vexing problem facing the South African economy. © Bishops Economics Department Page 11 Measuring prices: the consumer price index When the prices of goods and services increase, the purchasing power of our income decreases. A South African consumer can purchase much less with R100 today than in 1980, when prices were much lower. In other words the real value (or purchasing power) of R100 is much less today than it was in 1980. Instead of investigating what is happening to individual prices, economists use one of the price indices compiled and published by Stats SA. The one that is best known is the consumer price index (CPI). In the remainder of this section we explain the CPI. The consumer price index (CPI) The consumer price index (CPI): index of the prices of a representative “basket” of consumer goods and services. The CPI thus represents the cost of the “shopping basket” of goods and services of a typical or average South African household. In constructing the CPI, Stats SA… Assigns a weight to each good or service to indicate its relative importance in the basket Decides on a base year for calculating the CPI Collects prices each month to calculate the value of the CPI for that month To select the goods and services to be included in the basket and to determine their relative weights, Stats SA conducts a comprehensive, in-depth survey of household income and expenditure in South Africa. The weight allocated to each good or service is based on the relative importance of the item in the average consumer’s budget or “shopping basket”. This requires a lot of time and effort and is therefore done only every five years or so. Currently, the South African CPI was based on a household income and expenditure survey conducted in 2005/2006. The total CPI basket consists of more than 400 different consumer goods and services. These goods and services are classified into more than 40 groups and sub-groups for which separate indices are constructed. In addition, different CPIs are published each month for, inter alia, five expenditure groups, for pensioners, for the nine provinces and for 42 urban areas in South Africa. An average of around 100 000 prices are collected every month by Stats SA. © Bishops Economics Department Page 12 Measuring the links with the rest of the world: the balance of payments Each country keeps a record of its transactions with the rest of the world. This accounting record is called the balance of payments. The South African balance of payments summarises the transactions between South African households, firms and government, and foreign households, firms and governments during a particular period (usually a year). The balance of payments consists largely of two major accounts, the current account and the financial account. All the sales of goods and services to the rest of the world (ie exports), all the purchases of goods and services from the rest of the world (ie imports) as well as all the primary income receipts and payments are recorded in the current account of the balance of payments. All the purely financial flows in and out of the country, like purchases and sales of assets such as bonds and shares, are recorded in the financial account of the balance of payments. o If there is a surplus on the current account, exports > imports. o If there is a deficit on the current account, imports > exports. o Likewise, if there is a surplus on the financial account, funds flowing into the country > funds flowing out of the country. In this case we say that there was a net inflow of foreign capital into the country. o If there is a deficit, it indicates that funds flowing out of the country > funds flowing into the country. In this case we say that there was a net outflow of foreign capital into the country. © Bishops Economics Department Page 13 A detailed explanation of all of the figures in the table below follows… Current account Merchandise exports and imports: reflect the rand value of the goods exported and imported during the period. Net gold exports: net foreign sales of gold plus changes in the gold holdings of the Reserve Bank Together, they constitute what is often referred to as the trade balance. Service receipts: money spent by foreign tourists in South Africa Payments for services: money spent by South Africans when travelling abroad Income receipts: income earned by South African residents in the rest of the world Income payments: income earned by non-residents in South Africa. © Bishops Economics Department Page 14 There are two categories of income flows… Compensation of employees: wages, salaries and other benefits earned by individuals from countries other than those in which they are resident (ie from the rest of the world). Investment income: dividends, interest, profits and other forms of income earned from the provision of financial capital. Income receipts in the balance of payments are equal to the “primary income from the rest of the world” identified in the national accounts. Likewise, income payments in the balance of payments are equal to the “primary income to the rest of the world” identified in the national accounts. Remember… GNI + GDP + primary income from the rest of the world - primary income to the rest of the world. Current transfer account: includes social security contributions and benefits, taxes imposed by government, and private transfers of income such as gifts, personal, immigrant and other remittances and charitable donations. By transfers we mean money, goods or services transferred without anything tangible being received in return. Financial account The financial account records international transactions in assets and liabilities. The financial account has three main components… Direct investment: includes all transactions where the purpose of the investor is to gain control of or have a meaningful say in the management of the enterprise in which the investment is made (eg through the establishment of new businesses or the acquisition of shares in existing businesses). Portfolio investment: refers to purchases of assets such as shares or bonds where the investor is interested only in the expected financial return on the investment. Other investment: includes all financial transactions not included under direct investment or portfolio investment. It includes loans, currency and deposits. In the table on the previous page, direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment are all shown on a net basis. In other words, the outflows (debits) have been deducted from the inflows (credits). The balance on financial account can be obtained by adding net direct investment, net portfolio investment and net other investment. Surpluses were recorded on the South African financial account in 2009 and 2010. These surpluses were typical of the South African experience from 1994, with financial account surpluses generally being large enough to finance current account deficit. © Bishops Economics Department Page 15 Unrecorded transactions: all errors and omissions that occur in compiling the individual components of the balance of payments are entered as unrecorded transactions. Unrecorded transactions therefore serve to ensure that the balance of payments actually balances. Gold and other foreign reserves The sum of the current account balance, the capital transfer balance, the financial account balance and the unrecorded transactions is reflected in the change in foreign reserves. A portion of South Africa’s gold production is held by the SARB as part of the country’s foreign reserves. If necessary, the gold reserves can be sold to obtain foreign currency (eg US dollars). South Africa’s foreign reserves thus consist of gold and other foreign reserves. There is a difference between changes in net and gross foreign reserves. The change in net gold and other foreign reserves reflects the combined balance on the current, capital transfer and financial accounts and the unrecorded transactions. This is why it is described as the change “owing to balance of payments transactions”. The authorities can, how-ever, supplement the reserves by borrowing specifically for this purpose. This increases the country’s reserves, but the increase is only a “gross” change since the loans obtained have to be repaid as soon as the balance of payments improves. When the loans are repaid, the gross reserves decline accordingly. © Bishops Economics Department Page 16 Current account Merchandise exports: includes the trade in all physical goods, which consist of raw materials as well as intermediate and final goods. All exports of capital goods also fall into this category. Net gold exports: shown separately due to the traditional role of gold as a form of international currency and South Africa’s role as major gold producer. Service receipts: includes the transportation of goods and passengers between countries, travel, construction services, financial and insurance services, various business, professional and technical services, as well as personal, cultural and recreational services and government services. Income receipts: refer to income earned by South African residents in the rest of the world. There are two categories of income flow: compensation of employees and investment income. Compensation of employees: includes wages, salaries and other benefits earned by individuals in or from countries other than those in which they are resident (ie from the rest of the world). Investment income: includes dividends, interest, profits and other income earned from the provision of financial capital. Investment income is recorded in the current account, not the financial account. Thus, when a South African purchases shares in a British company on the London Stock Exchange the value of the shares purchased is recorded in the financial account but any subsequent dividend receipts are recorded as income receipts in the current account of the South African balance of payments. Merchandise imports, payments for services and income payments: calculated on the same basis as merchandise exports, service receipts and income receipts respectively. The main difference, of course, is that the income or expenditure flows are in the opposite direction, that is, from South African residents to the rest of the world. Current transfers: money, goods or services are transferred without receiving anything tangible in return (ie without any quid pro quo). Examples include gifts, personal, immigrant and other remittances and charitable donations. Balance on current account: the net total of all the various items in the current account. Capital transfer account: the capital transfer account is relatively insignificant. Capital transfers are offsetting transactions to the transfer of the ownership of fixed assets, transfers of funds associated with the acquisition or disposal of fixed assets, debt forgiveness and transfers by migrants (eg the value of household or personal effects as well as financial claims and liabilities transferred by migrants from their former to their new countries of residence). Financial account The second main subaccount of the balance of payments is the financial account, which records international transactions in assets and liabilities. It has three main components. Direct investment: includes transactions related to the acquisition of share capital in foreign countries by establishing new businesses, or through mergers and takeovers. The purpose of the investor must be to gain control of or meaningful say in the management of the enterprise in which the investment is made, for example by purchasing a substantial share of a foreign company © Bishops Economics Department Page 17 or by setting up a foreign branch or subsidiary. Portfolio investment: refers to the purchase of assets such as shares (equities) or bonds where the investor is interested only in the expected financial return on the investment. In other words, the investor is not aiming to gain control of or meaningful say in the management of the enterprise in which the investment is made. Other investment: a residual category which includes all financial transactions not covered under direct investment, portfolio investment or reserve assets. It includes trade credits, loans, currency and deposits and other assets and liabilities. Balance on financial account: obtained by adding net direct investment, net portfolio investment and net other investment. Unrecorded transactions: in principle, the net sum of all credit and debit entries should equal the change in the country’s net gold and other foreign reserves (see below). In practice, however, this does not happen since errors and omissions occur in compiling the individual components of the balance of payments. The net effect of these errors and omissions (including differences in coverage, timing and valuation), are entered as unrecorded transactions. In practice, therefore, the unrecorded transactions, which pertain to the current, capital transfer and financial accounts, serve to ensure that the overall balance of payments actually balances. Official reserves account The last element of the balance of payments is the official reserves account. A country’s official reserves consist of gold, special drawing rights (SDRs) issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the country’s IMF reserve position and foreign exchange reserves. The foreign exchange reserves are held in the form of gold, foreign bank notes, demand deposits with foreign banks and other claims on foreign countries which can readily be converted into foreign bank demand deposits. In South Africa the official reserves are called gold and other foreign reserves. The combined current account, capital transfer account and financial account balances and unrecorded transactions yield the change in the country’s net gold and other foreign reserves owing to balance of payments transactions. In principle, this constitutes the balancing item for the overall balance of payments. However, as mentioned earlier, the value of unrecorded transactions has to be included to ensure that the balance of payments actually balances. The change in the country’s gross gold and other foreign reserves during a particular period is obtained by adding two further items to the change in the net reserves. They are the change in the liabilities related to reserves and SDR allocations and valuation adjustments. The change in liabilities related to reserves is the net result of official short-term loans obtained specifically to bolster the reserves and any repayment of such loans. The second item consists of valuation adjustments and allocation of SDRs by the IMF. SDRs are a form of credit which can be used when balance of payments difficulties are experienced. The valuation adjustments have to be made because the gold reserves are valued at a market-related price, which varies from month to month. © Bishops Economics Department Page 18 Measuring Inequality: The Distribution of Income The fifth macroeconomic objective concerns the distribution of income among individuals or households. To obtain an accurate picture of the distribution of income we must have reliable information about the income of each individual or household in the economy during a particular period. This information is difficult to obtain. Estimates of the distribution of income are therefore undertaken only sporadically. In this section we explain three of the measures that are often used to measure the equality or inequality of the distribution of income, once the necessary basic information has been obtained. Lorenz curve Named after the American statistician Max O. Lorenz who developed it in 1905, the Lorenz curve is a simple graphic device which illustrates the degree of inequality in the distribution of income. To construct the Lorenz curve illustrating the distribution of income, the different individuals or households in the economy first have to be ranked from poorest to richest. This is done on a cumulative percentage basis. The cumulative percentages of the population are plotted along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis shows the cumulative percentage of total income. © Bishops Economics Department Page 19 © Bishops Economics Department Page 20