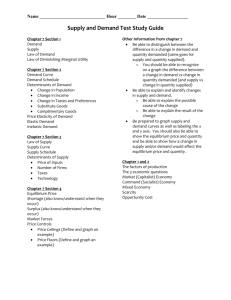

Supply and Demand

advertisement

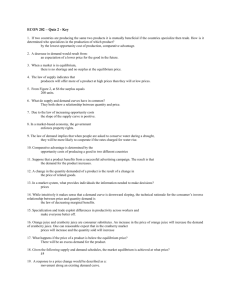

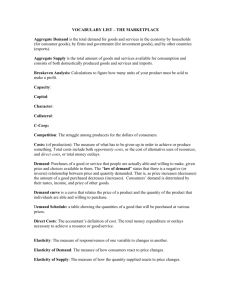

Supply and Demand, and Market Failure Economics looks at the world from a perspective of choices we make given our limited resources. Economics - the study of how society manages its scarce resources Or the study of how to detect unintended consequences. 1. People face tradeoffs Scarcity-- Limited nature of society's resources (unlimited wants, limited resources) 2. The cost of something is what you give up Opportunity Cost - the highest valued alternative to choosing an action Health economics studies how resources are allocated to and within the health economy. There are special challenges to healthcare managers 1. The central roles of risk and uncertainty – both the incidence of illness and the effectiveness of care are described in terms of probabilities. These change our behavior. Even the correct therapy, provided the right way may carry some risk of failure. 2. The complexities created by insurance – because of risk and uncertainty, most consumers have medical insurance. This puts a wedge between the payer and the user and has a huge impact on incentives. It also complicates even the simplest transaction – now there are at least three parties involved in any transaction. 3. The perils of information asymmetries – not only is there incomplete information (uncertainty), there is also often asymmetric information. This can lead to a type of market failure known as adverse selection – or death spiral. 4. The problems posed by not-for-profit organizations – multiple stakeholders mean multiple goals. Thus, organizations become harder to manage and managerial performance becomes harder to assess. How do nonprofits and for profits compete in the same market? 5. The rapid and confusing course of technical and institutional change – Technology is widely credited as the main driver for increasing health care costs. But is this driven by demand or supply? 6. The move from volume to value Supply and Demand Demand The Law of Demand There is an inverse relationship between the price of a good and the amount of it consumers choose to buy Two effects of a price change: Income effect – lower price means that a consumer’s real purchasing power increases, which increases the consumption of the good and likewise for a price reduction. Substitution effect – when the price of one good falls, the consumer has an incentive to increase consumption of that good at the expense of the other, now relatively more expensive goods. Determinants of individual Demand 1. Income 2. Prices of related goods 3. Tastes 5. Expectations Demand Schedule and Demand Curve Price D Quantity Market Demand vs. Individual Demand -- market demand is horizontal summation of individual demand curves Shifts in the Demand Curve Change in prices of related goods Change in income (normal and inferior goods) Change in tastes Change in Expectations Price elasticity of demand and its determinants Defn: Price elasticity of demand -- a measure of how much the quantity demanded of a good responds to a change in the price of that good. Determinants: Necessities vs. luxuries Availability of close substitutes Definition of the market Time horizon Variety of Demand Curves Supply There is a direct relationship between the price of a good and the quantity supplied Determinants of individual Supply 1. input prices 2. technology 3. expectation The Supply Schedule and the Supply Curve Price Supply Quantity Market Supply vs. individual Supply Shifts in the Supply Curve Change in the price of inputs Change in technology Change in the number of suppliers Price Elasticity of Supply Supply and Demand Together Price Equilibrium Supply 75 50 25 Demand 50 100 150 Quantity Note that the only stable price here is 50. If the price is set at, say 75, then the quantity demanded will be 50 and the quantity supplied will be 150 so there will be a surplus of 100 units of the good. This would put downward pressure on the price (firms trying to unload unsold goods). Likewise if the price is set at, say 25, then the quantity demanded will be 150 while the quantity supplied will be only 50 so there will be a shortage of 100 units. This will put upward pressure on the price (consumers scrambling to try and get one before they are sold out). The only place price will stay put is at 50 – here quantity demanded just equals quantity supplied – everyone who wants to buy at a price of 50 is able to, and everyone who wants to sell at 50 is able to. Thus, there is no tendency to change – equilibrium. Is this equilibrium good? Allocative efficiency – we are producing the right amount of this good from society’s standpoint. Consumer Surplus – a measure of how much better off consumers are because this market exists. This is represented by the area above the price but below the demand curve. Eg—the consumer would have paid 75 for the 50th unit, yet they only paid 50. So they are $25 better off. Do this for all units between 0 and the equilibrium quantity (100) and you get consumer surplus. Producer Surplus – a measure of how much better off producers are because this market exists. If the firm had no fixed costs this would be equal to profit. This is represented by the area below the price but above the supply curve. Eg – the firms would have sold the 50th unit for 25, yet they got 50 for it, so they are $25 better off. Do this for all units between 0 and the equilibrium quantity (100) and you get consumer surplus. Total welfare = Producer + Consumer Surplus Note that under the market equilibrium total welfare is maximized. Thus what the free market produces “best” amount to produce from society’s standpoint – it is allocative efficient. Changes in Equilibrium The market for pizza when the price of tomatoes increases The market for pizza when the price of beer increases 1. Health reform that succeeds in covering many of the uninsured. How would this affect the markets for health care in the short run? 2. Hospitals can hire only baccalaureate RNs. How would this affect the market for hospital care? 3. Government lowers reimbursement rates paid to physicians for Medicare patients. How would this affect the market for non-Medicare patients? 4. What about when Medicare lowers DRG rate to hospitals? How does this impact prices to non Medicare patients? Market Failure We just described how the free market results in the outcome that is the best outcome from society’s standpoint. This is often the case but there are some assumptions we make to get there. We will get into those in more detail later, but there are a few situations where the market does not produce an efficient level of output. I. Public Goods, Common Resources, and Natural Monopolies Any good or service can be characterized by two attributes: Rivalry -- if one person consumes the good, does it go away? Excludability – is it possible to exclude non-paying customers? By this there are 4 types of good: 1. PRIVATE GOODS – rival and excludable. The market does a good job of producing these types of goods. To steal an example from Dr. Shay: Sandwich it is rival – if I eat it, it is not there for anyone else to eat. It is excludable – if you don’t pay for it you can’t have it. 2. PUBLIC GOODS – nonrival and nonexcludable. The market doesn’t do so well here. Firework show, national defense, music, aerobics class Problem is freeriders – I have an incentive to wait until someone else buys it then use theirs (think group project with a single grade). But we all have this incentive so the market tends to either not produce the good at all, or it will produce too little from society’s perspective. 3. COMMON RESOURCES – rival and nonexcludable. The market doesn’t do too well here either. Creates a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation Fisheries, wildlife, clean air and water, congested roads, etc. healthcare??? 4. NATURAL MONOPOLY – nonrival and excludable. We will see this from a different angle next week. But think about cable tv, power companies, a noncongested toll road. Bottom line: Markets do best when goods are rival and excludable – they struggle (or fail completely) when nonrival and (especially) nonexcludable. II. Externalities One of the assumptions we made when we talked about the supply and demand graphs was that all of the costs of producing the good were incurred by the firms producing it, and all of the benefits of consuming it were enjoyed by those actually consuming it. This is normally how it is, but not always – and when this is not the case the market tends to not do too well. 1. Negative Externalities in production Think about producing electricity by burning coal – much of the costs are transportation, running the factory, etc. These are “internal” costs that are completely borne by the firms producing electricity. However, there are other costs – when coal is burned it puts pollution into the air. This imposes “external” costs on individuals who are not involved with the decision to produce electricity. 100 Total Cost (social costs) C B 75 50 Internal Cost (supply) A Demand 75 100 In this case note that since there are both internal and external costs, there are two cost curves. The firm only cares about the internal costs so when it is considering how much of the good they are willing to sell at any given price, they ignore the external costs and only pay attention to the internal costs. In this case the market equilibrium is at point A: Price = 50, quantity =100. But note this is NOT allocatively efficient. The market is producing 100 units – the value of the 100th unit is $50 to the consumer BUT the (total) cost of producing it was 100. So we took resources valued at 100 and converted it into a good that is worth 50 – not so good. The market over-values the good. The loss to society because of this is the area ABC The efficient level of output would be point B – this is where the total cost crosses the demand curve. So 75 is the allocatively efficient level of output, and the price would be 75. When there are negative externalities the market tends to produce too much of the good and it is priced too low from what would be best for society. Usually the solution here is to tax the production of this good – to internalize the external costs. 2. Positive Externalities in consumption. Another situation is when the benefits of the good are not solely enjoyed by the consumers of the good. A classic example is education. Getting an education not only benefits those getting the education but others – (you are more interesting to talk with, you contribute to society, etc.). So if left to its own devices the market will produce too little of the good. 100 C Supply 75 B 50 Social Benefits A Internal benefits (demand) 75 100 Here note that there are benefits that go to those “external” to the market so the demand curve does not reflect the full social benefits of the good. The market equilibrium (point A) is where the supply curve crosses the demand (internal benefits) resulting in 75 units at a price of 50. Note from society’s standpoint this is too little. Note that the 75th unit of the cod costs of 50 to make but is worth 100 – we would benefit with more of this good than what the market produces. The market undervalues that good. The area CBA represents how much better off we would be as a society if we produced the efficient level of output When there are positive externalities the market tends to produce too little of the good and it is priced too low from what would be best for society. Usually the solution here is to subsidize the consumption of this good – to internalize the external benefits. Hence we have public schools, generous student loan programs, etc. III. Market power We will talk more about this next week – but one of the assumptions we make when we draw the supply and demand curve above is that there are many firms producing the good. If there is only one firm (or just a few) then things don’t work as smoothly – the market will tend to produce too little of the good and charge too much IV. Information Asymmetry Again, we will spend a lot of time on this later since it is a huge deal in health care markets, but when one side of the market has more information than the other (the buyers of insurance often have a much better idea of their risk than the sellers, or the seller of a used car might know much more about the quality of the car than a potential buyer) the market can struggle – even can fail completely resulting in a “death spiral” What if we don’t like the market price? Even though the market equilibrium is, in general, an efficient allocation of resources, we may not like it – or think it isn’t “fair”. What can be done? Suppose we consider the market for housing. Keep it simple and assume there is one quality level so a single product: C Supply B 1000 750 F D A E Demand 75 100 125 The market equilibrium is a price of 1,000/month with a quantity of 100 units. We want to make housing more affordable since 1,000 is a lot. If we had a lower price then more people could afford to live on their own and the world would be a better place. So let’s set a price ceiling at $750/month as the maximum price that can be charged. What will happen? At a price of $750, more people want to buy an apartment – quantity demanded goes from 100 to 125 (so 25 new people can now afford a place). But note that quantity supplied shrinks. Only 75 apartments are available to rent. So this creates a shortage of 50 apartments – 25 new entrants can’t find one, but note also that there were 25 people who used to have an apartment who can no longer find one. The consumers who are able to get an apartment are potentially made better off but note there is a net loss in welfare. Total welfare goes from CFE prior to the price control to CBAE after the price controls are imposed. A net loss of BFA is incurred. Secondary effects – quality, discrimination, etc. The elasticity of the supply curve will be important here. What happens when we tax a market? Suppose we consider the market for gasoline. In order to raise money to pay for street repair the state decides to impose a $.50 per gallon on the sales of gasoline. Gasoline sellers are required to send $.50 per gallon of gasoline they sell to the state at the end of each month. How does this affect the market for gasoline? Supply w/ tax 2.50 Supply D 2.25 E 2.00 F 1.75 G B A C H Demand 100 150 Before the tax the market is in equilibrium at point A – price is $2.00 and 150 gallons are sold. When the tax is imposed, note this can be thought of as a cost to the firm. So for any given quantity, it costs an extra $.50 to produce the good – supply shifts up by $.50. But note price cannot go to 2.50 – since if it did demand would drop to close to zero. Instead the new equilibrium is at point B. The new quantity is 100 – so they make 100*.50=$50 in tax revenue (not $150*.50=$75 which some would expect). The price that consumers pay goes to $2.25, and the price that firms get to keep (after paying the tax is 2.25-.5=1.75. So consumers are paying an extra .25 and firms get .25 less because of the tax. In this case the burden of the tax is split evenly between firms and consumers. In general the burden of the tax is a function of demand and supply elasticity (draw some of these). What are the net effects of this tax on society’s well being? Prior to the tax: Consumer surplus = DAF Producer surplus = FAH Note this is maximizing social welfare: DAH After the tax: Consumer surplus = DBE Producer surplus = GCH Tax revenue = EBCG Total welfare = DBCH So note the area BAC is lost because of the tax