Language acquisition

advertisement

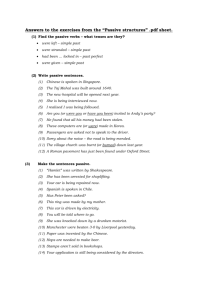

35 years of Cognitive Linguistics Session 10: Language acquisition Martin Hilpert your questions • • • • Want other one spoon, Daddy. It noises. I becamed to be Spiderman. She unlocked it open • buzz, crash, splash, bang, noise • It buzzes, crashes, splashes, bangs, ... • * It noises. • pull, crack, pry, unlock • She pulled / cracked / pried / it open. • *She unlocked it open. overgeneralization errors • The child has acquired more than a string of word that is repeated. • The error shows that the child has acquired an regularity. • It also shows that the child has not yet mastered all constraints on that regularity. • If children make overgeneralization errors, this must mean that they have acquired an abstract rule, right? • She unlocked it open. SUBJ V-ed OBJ ADJ The dictionary-and-grammar model dictionary-and-grammar model vs. CxG • Both models assume that children learn generalizations. • The models have different hypotheses about how the process of language learning unfolds. two hypotheses • dictionary-and-grammar: the continuity hypothesis – children acquire the syntactic categories (SUBJ, ADJ, etc.) and rules of adult grammar – at first their language output is imperfect because not all rules are in place • CxG: the item-based learning hypothesis – children acquire knowledge of lexical items and fixed strings of lexical items (more juice) – as they acquire more and more of these, they begin to form generalizations across them the continuity hypothesis • The language of children is mentally represented by the same syntactic rules and categories as adult language. • Innate knowledge facilitates the learning process. • POS categories are fundamental. S. Pinker not S. Pinker the continuity hypothesis • ‘Once a child is able to parse an utterance such as « Close the door », he will be able to infer from the fact that the verb « close » in English precedes its complement « the door » that all verbs in English precedes their complements.’ • >> This only works if children are born with the idea that there are verbs, complements, and relative clauses. item-based learning • Children start out by memorizing and repeating concrete words and phrases. • As a child recognizes similarities across different phrases, a process of schematization sets in. • POS categories and syntactic constructions emerge as generalizations over concrete phrases • Generalizations get increasingly abstract, until they resemble adult grammar. foundations of language learning five socio-cognitive abilities 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. joint attention intention reading schematization role reversal pattern recognition 1. joint attention • Words become meaningful in situations in which both the child and a caretaker focus on an object and are mutually aware of this. • Before 9 months of age, children can only engage in dyadic joint attention (mutual eye gaze). • Triadic joint attention means inspecting an object together. • With the ability to engage in triadic joint attention comes word learning. 2. intention reading • Young children interpret other people’s actions as purposeful and goal-directed. • Theory of mind: other people too have ideas, feelings, knowledge. • Toddlers imitate actions of others, but only those that they see as ‘successful’, not those that are ‘accidental’. 3. schematization • • • • all done, all wet where’s daddy?, where’s cookie? let’s go!, let’s find it! I’m holding it, I’m pulling it >> all X >> where’s X >> let’s X >> I’m X-ing it • the ability to form pivot schemas – Pivot: the fixed part of a schema – Open slot: the variable part of a schema 4. role reversal • In linguistic interaction, speakers are also hearers, and vice versa. • the capability of conceptual blending – What would it be like if I were in the position of my interlocutor? – Creating a model of other people’s current knowledge. 5. pattern recognition • the ability to recognize regularities in speech • 8-month old infants listened to nonce words – bidaku, padoti, bidala, tupiro, gobida, ... – bi always followed by da • exposure to new words – bidaka >> in line with previous words – dabiko >> different from previous words • infants showed greater interest towards words that violated established patterns five socio-cognitive abilities 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. joint attention intention reading schematization role reversal pattern recognition generalizing across pivot schemas • easier with English nouns than with English verbs • noodles in there, my noodles, noodles hot – __ in there – my __ – __ hot • verbal pivot schemas – introducing ‘meeking’: 2-year olds hesitate to use the form, even though they have pivot schemas with ing-forms (I’m holding it, I’m pulling it) the verb island hypothesis • verbs in early language acquisition form ‘islands’ of grammatical organization – – – – each verb is limited to a single syntactic pattern tickle me, tickle it, tickle doggie put it there, put it up, put it down I swinging, baby swinging • adults use these verbs in several syntactic patterns – Stop tickling, John was tickled by Mary, John tickled me silly, John tickled Mary out of the room, … Evidence for item-based learning 1. Children are conservative about verbal pivot schemas (Brooks and Tomasello 1999) study questions 1. Can very young children be trained to use the passive? – If they can, it is likely that input frequency, not overall complexity, explains the absence of passives. 2. Can these children then use the passive productively? – If they learn a new transitive verb, do they immediately conclude that it can be ‘passivized’? • 28 younger children (~2.5 years), 28 older children (~3.5 years) • both groups saw transitive actions described as meeking and tamming meeking meeking tamming tamming training phase: two conditions • active training group – – – – Look, the fraggle is meeking the banana! Oh wow, the robot just tammed the banana! Who’s meeking the banana? Did you see who tammed the banana? • passive training group – – – – Hey, the banana got meeked by the fraggle! See how the banana got tammed by the robot? What’s going to get meeked? I think something is getting meeked again… test phase: elicitation • neutral question – What happened? • patient-focused question – What happened to the banana? • agent-focused question – What did the fraggle do? • purpose – Can children adjust their use of novel verbs to the discourse needs (patient-focused, agent-focused)? results: passive formations 100 *** 60 40 Main effect of training group: active-trained kids – very few passives 20 percent of children using a passive 80 neutral patient agent young passive old passive young active group old active results: passive formations *** 100 *** 60 Main effect of question type: agent-focused question - fewer passives 40 *** *** 20 percent of children using a passive 80 neutral patient agent young passive old passive young active group old active 100 results: passive formations 40 60 Interaction between training group and question type: question type makes a much larger difference in the passive-trained group 20 percent of children using a passive 80 neutral patient agent young passive old passive young active group old active results: passive formations n.s. 100 n.s. 60 40 No effect of age 20 percent of children using a passive 80 neutral patient agent young passive old passive young active group old active 2. Children’s linguistic creativity has been overestimated (Lieven et al. 2003) How creative are children in their language use? • Low creativity with gradient increase – evidence for a usage-based model that starts with items • Initially low and then suddenly high creativity – evidence for a rule that is acquired and can be freely applied after that How do children acquire constructions? • continuity hypothesis – start with lexically fixed phrases – acquire an adult syntactic rule – productively apply that syntactic rule • item-based learning hypothesis – start with lexically fixed phrases – vary individual items in slots – arrive at a broader generalization How can these hypotheses be assessed? • Evidence – A high percentage of all recorded constructions in a dense child language corpus have been produced before or are found in the input. assessing creativity • • • • • • change substitution add-on drop insertion rearrangement Target I got the butter Let’s move it around And horse finished with your book? Away it goes Predecessor I got the door Let’s move it And a horse finished your book? It goes away • Each new utterance can be related to earlier utterances in terms of how many steps of change are necessary. data • two children – each recorded for 6 weeks at age 2, then again for 6 weeks at age 3 – four high-density corpora, divided into main and test How creative are young children? 0 changes 0 50 100 1 change 150 200 total number of multi-word utterances 2 250 3 300 types of ‘failed’ derivations • inappropriate filler – Do you want to football? – inappropriate filler in the PROCESS slot • inappropriate add-on – Which ones go by here? – inappropriate prep added to Which THING go here? • constituent omission – And what that done? – Omission of has in And what has that done. failed derivations • A high proportion of the problematic utterances are ill-formed by adult standards – When children use language creatively, they go beyond what they know, rather than applying abstract rules to create novel utterances. conclusions • The creativity of later child speech has been overestimated: – Small variations account for the lion’s share of all utterances. – The variation that does exist does not point to the application of rules. – Rather, item-based learning continues as the main process of language acquisition, is not abandoned in favor of learning abstract principles. 3. The collocational properties of constructions facilitate acquisition How are constructions learned? • Children must learn that there are correspondences of syntactic form and meaning: – John emailed me the report. • Learners must be able to interpret novel utterances: – ‘fast mapping’ – children learn lexical items at a stunning rate – is this also possible with syntactic constructions? How are constructions learned? • Idea: Learning might be easy if a syntactic structure often occurs with one particular lexical element. Many constructions have a most frequent verb: experiment • a new English phrasal pattern with a new meaning – NP1 NP2 VERB-o ‘appearance’ – The frog the sock moopoed • Training: Participants heard sentences and watched video sequences in which an animal/toy spontaneously appeared • Task: Participants were given one sentence and had to choose between two possible video clips training “The frog the sock moopoed” critical trial “The cow the hat moopoed” experiment • Procedure: subjects saw eight clips • Stimuli: visual display sound experiment • Three groups: – The skewed frequency group (4-1-1-1-1) – The balanced frequency group (2-2-2-1-1) – The control group (no sound) results • The control group did not perform better than chance • Both the skewed input group and the balanced input group performed well, the skewed input group outperformed the balanced group. summing up a usage-based view of language acquisition • Cognitive Linguistics tries to explain language acquisition without positing an innate language faculty • Instead, language learning is explained in terms of domain-general cognitive abilities: – – – – – joint attention intention reading schematization role reversal pattern recognition evidence for item-based learning 1. Children extend verbal pivot schemas conservatively. 2. Children’s linguistic creativity has been overestimated. 3. Skewed frequencies of collocates facilitates the learning of constructions. See you next time! martin.hilpert@unine.ch