File

advertisement

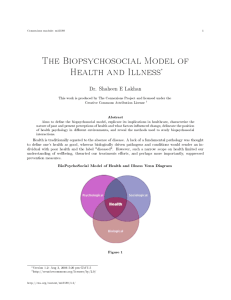

Shiven Patel English 137H Paradigm Shift Essay Traditional U.S. Health Care has long focused on the physical well being of patients, because it has greater value, greater resources available, and easier access to physical problems. However, this traditional view had to be adjusted due to its inability to deal with chronic disease. Seven out of ten deaths among Americans each year are from chronic diseases–heart disease, cancer and stroke–which account for more than 50% of all deaths each year. The state of mental healthcare in the United States was (and still is) perplexing, to say the least. This perplexity spawned the Biopsychosocial (BPS) revolution, marking a major paradigm shift in the field of medicine. Since Louis Pasteur’s laboratory research of the germ theory in the 1860s, Western medicine has been primarily fixated on biological factors when dealing with patients. The known existence of germs actually preceded the theory by more than two centuries. The first documented moment when germs were acknowledged dates back to 1677, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek used the first simple microscope to see tiny “animalcules.” These “animalcules” were tiny organisms in the droplets of water he was examining. Leeuwenhoek never made a proper correlation between these “animalcules” and disease, saying germs were an effect of disease, rather than the cause. Since the popular theory at the time was spontaneous generation, Leeuwenhoek’s assertion seemed to make sense. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek provided a solid foundation of data for future scientists to conduct more research on. Louis Pasteur used experiments and microscopes to find that liquids such as beer and milk went off because of the rapid multiplication of very small organisms–germs–in that liquid. Pasteur’s research led to the widespread acceptance of his germ theory, which stated, “that many diseases are caused by the presence and actions of specific micro-organisms within the body.” Pasteur’s theory provided a guideline for Western medical practitioners, leading to the formulation of the Biomedical Model. Brett J. Deacon states, “The biomedical model posits that mental disorders are brain diseases and emphasizes pharmacological treatment to target presumed biological abnormalities.” In other words, the model states that mental disorders such as ADHD, schizophrenia and depression are biologically based brain diseases. The core principles of this model include: “there is no meaningful distinction between mental diseases and physical diseases” and “mental disorders are caused by biological abnormalities principally located in the brain.” The ascendancy of this model yielded notable progress in neuroscience and molecular biology. However, Deacon recognizes that what was often overlooked in the context of widespread enthusiasm for the Biomedical Model was “the fact that mental health outcomes in the United States are disconcertingly poor.” George L. Engel directly challenged the concept of “mind-body dualism” in his renowned 1977 article in Science journal. Titled “The Need for a New Medical Model,” Engel criticized both the fields of medicine and psychiatry for, “adhering to a model of disease no longer adequate for the scientific tasks and social responsibilities of either medicine or psychiatry.” Engel relates the Biomedical Model to a dogma, since a dogma requires that data be forced to adhere to a model or be excluded. This point, echoed by Deacon, stresses there are issues at hand with the current model, which are being overlooked. In this article, Engel proposes a new model–one that does not have the limitations of the Biomedical Model. The Biomedical Model fails in introducing a psychiatric perspective to diseases. For example, Engel states that if we were to think of patients with diabetes and schizophrenia in exactly the same terms, we would see how focusing only on biological factors while ignoring psychosocial perspectives would greatly interfere with proper patient care. Engel’s new model is called the Biopsychosocial Model, which incorporates biological, psychological, and social factors when diagnosing and treating diseases. Engel argues that the “Biopsychosocial Model which includes the patient as well as the illness would encompass [all] circumstances.” When all circumstances are accounted for, rather than giving primacy biological factors (which the Biomedical Model does), there is a higher possibility of explaining why some individuals experience “illness” conditions while others regard those conditions merely as problems of living. The Biopsychosocial Model presents a more effective alternative to the preceding model, and rationale that better links medicine to science. The main difference between the models is that the newer model incorporates psychological and social factors, meaning there is a greater emphasis on provider-patient relationships. Robert C. Smith argues that by incorporating biological aspects in addition to psychosocial aspects, “we become more humanistic.” By following this new approach, the patients’ needs are put ahead of the disease issues, which enhances communication and provider-patient relationships. This integrated model provides practical means for a more scientific understanding of each patient. 2012 President of the American Psychological Association Suzanne Bennett Johnson argues that “patient-centered care” is the future of U.S. Health Care. Johnson also acknowledges these issues come from the notion of “mind-body dualism.” This is the theory that the mind and body are distinct kinds of entities, and do not relate to one another. Johnson condemns traditional U.S. medical approaches for having prioritized physical health (the body) while paying no attention to the mental health (the mind). Furthermore, mental health and physical health providers were trained separately, with physical health providers having “greater resources and prestige.” The separation of physical and mental health was the underlying issue in the Biomedical Model, and this problem was addressed by the proposition of the Biopsychosocial Model. In patient-centered care, the patient is treated as one whole person (without mind-body dualism) and both the mental and physical needs of the patient are addressed. Also in patient-centered care, the patient is treated by inter-professional health teams, which includes physical and mental health expertise, and is situated “in a non-stigmatizing environment that considers the patient’s preferences and culture.” Looking at recent history, the Biopsychosocial Model has been accepted in the United States. Treatment utilization trends, grant funding priorities, the language used to describe psychiatric diagnoses, and psychotherapy research methodology have progressively adopted the Biopsychosocial Model in recent decades. Medicine is now embracing the Biopsychosocial Model, emphasizing patient-centered care delivered by interdisciplinary provider teams that include mental health expertise. The Affordable Care Act requires that essential health benefits include mental health, preventive and wellness services. The MCAT (Medical College Admission Test) now includes the same number of items on psychological, social and biological foundations of behavior as it has on biology or biochemistry. Lastly, medical schools are now required to teach patient-provider communication skills, the medical impact of common societal problems, and the impact of patient culture and beliefs. The paradigm shift from biological factors to the integration of psychology into medicine is evident in the shift from the Biomedical Model to the Biopsychosocial Model. SOURCES: Deacon, B. J. (2013). The Biomedical Model of Mental Disorder: A Critical Analysis Of Its Validity, Utility, And Effects On Psychotherapy Research. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(7), 846-861. Engel, G. (1977). The Need For A New Medical Model: A Challenge For Biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129-136. Johnson, S. B. (2012). Psychology's Paradigm Shift: From A Mental Health To A Health Profession?. Monitor on Psychology, 43(6), 5. Smith, R. C. (2002). The Biopsychosocial Revolution. Interviewing And Providerpatient Relationships Becoming Key Issues For Primary Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17(4), 309-310. Wade, D. T. (2004). Do Biomedical Models Of Illness Make For Good Healthcare Systems?. BMJ, 329(7479), 1398-1401.