Day 2 PowerPoints

advertisement

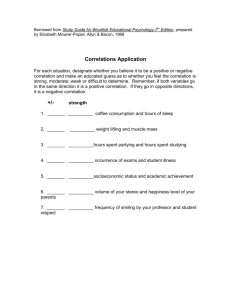

Day 2 Evolution of Decision-Making Tversky and Kahneman, 1974 Heuristics – general rules of thumb, or habits Generally result in decent estimates Can be fooled with systematic biases 2 Judging probabilities by the degree to which A is representative of B Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in antinuclear demonstrations. Please check the most likely alternative: Linda is a bank teller Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement 3 Most people (9 out of 10) answer B However, B is more specific than A and is a smaller subset of the population, therefore is not more likely Bank Tellers Feminists Bank Tellers who are also Feminists 4 Belief that random samples of a population will resemble each other The mean IQ of a population of eighth graders in a city is known to be 100. You have selected a random sample of 50 children for a study of educational achievements. The first child tested has an IQ of 150. What do you expect the mean IQ to be for the whole sample? 5 First child has IQ of 150 Remaining 40 have mean IQ of 100 Total is 5050, average is 101, not 100 We expect remaining sample to somehow “balance out” Small samples don’t randomly cancel out outliers with other outlier values Fallacy of the Hot Hand 6 Heuristic in which decision-makers “assess the frequency of a class or the probability of an event by the ease with which instances or occurrences can be brought to mind What is a more likely cause of death in the US – being killed by falling airplane parts or by a shark? Death by falling airplane parts is 30 times more likely, but shark death is more easily imagined 7 When imagination is limited When imagining an event is so upsetting that it leads to denial 8 9 Tversky and Kahneman 1981 define framing as “the decision maker’s conception of the acts, outcomes, and contingencies associated with a particular choice” Frames are partly controlled by formulation of the problem, and partly controlled by norms, habits, and characteristics of the decision maker 10 Decision 1 (risk aversion with gains at stake) Alternative A – a sure gain of $240 Preferred Alternative B – a 25% chance to gain $1000, and a 75% chance to gain nothing Decision 2 (risk seeking with losses at stake) A sure loss of $750 A 75% chance to lose $1000, and a 25% chance to lose nothing Preferred 11 Classic exercise in loss aversion Two choices presented to respondents They had to choose option A or option B 12 The United States is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill six hundred people. If program A is adopted, two hundred people will be saved; if program B is adopted, there is a one-third probability that six hundred people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. Which program do you favor? 13 When asked of physicians, 72% chose option A, the safe-and-sure strategy 14 The United States is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill six hundred people. If program C is adopted, four hundred people will die. If program D is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that six hundred will die. Which of the two programs do you favor? 15 When described in terms of deaths rather than lives saved, physicians reversed their choices, with 78% selecting option D, the risky strategy Both scenarios are identical in lives lost or saved Loss aversion is a way of skipping the math and using emotion to make the decision 16 17 Bernoulli 1713 Linear model of utilities Six axioms of expected utility theory Plous p. 81 Ordering of alternatives – comparing choices Dominance – some better than others Cancellation – common factors cancel out Transitivity – if a>b and b>c, then a>c Continuity – gamble preferred over intermediate Invariance – not affected by presentation style 18 Herbert Simon, 1955 First major advance in decision theory since Bernoulli’s in 1700’s Better match to real world decision-making Satisfice rather than optimize Satisficing finds alternative that meets most of the major criteria, then stops Example – apartment search in Arlington 19 Feature 1 Feature 2 Feature 3 Feature 4… Feature n Price Nearness Size Security Neighbors Complex 1 $650 2 miles 800 sq ft Limited Flight att. Complex 2 $600 3 miles 810 sq ft None Cars on blocks Complex 3 $350 4 miles 600 sq ft None Lots of kids Complex 4 $850 1 mile 900 sq ft Gated Nearby sorority Complex 5… $1200 Complex n $900 20 Lichtenstein (1971) Utility theory doesn’t quite all aspects of consumer behavior Rating of attractiveness (a weight applied to a probably outcome) A gamble is seen by the authors as a multidimensional stimulus Some dimensions of affect are playing a role in what should be a cognitive decision 21 Kahneman and Tversky, 1979 Replaces “utility” concept with “value” Utility is defined in terms of net worth Value is defined in terms of gains and losses Losses loom larger than gains Endowment effect What one owns is more valuable than what someone else owns 22 The value of each outcome is multiplied by a decision weight Decision weights are very subject to biases This leads to a decidedly n0n-symmetrical value function, where the value function for losses is decidedly steeper than that for gains 23 Outcomes with small probabilities are overweighted relative to outcomes with higher certainty This tendency leads to the concepts of insurance and gambling as industries 24 High Value Losses Gains Low Value 25 Example of $1 found by a millionaire or a homeless person – who values the incremental $1 more? Who would be more concerned with the loss of that incremental $1? For gains, this produces risk aversion For losses, this produces gambling 26 Damasio and Loewenstein investing game In each round, subject decides to invest $1 or invest nothing No invest, subject keeps dollar Invest, researcher flips coin for $1 loss or $2.50 gain Rational investors should always choose to invest 27 Decisions made relative to a reference point Comparison of imaginary outcomes referred to as “counterfactutal reasoning” Regret is based on two assumptions: People experience sensations of regret and rejoicing When making decision under uncertainty, people try to anticipate and take into account these sensations 28 29 People tend to evaluate personal risk outcomes based on the valence Positive outcomes – more probable Negative outcomes – less probable Rose colored glasses as a lens to our lives 30 Conjunctive compound events are A+B, where A and B are simple events Compound events are preferred when conjunctive Simple events are preferred when compound events are disjunctive (A or B) People anchor on the probabilities of the simple events that make up the compound event and fail to adjust probabilities 31 Once we estimate probabilities, we are slow to modify those estimates When modified, the estimates are changed more slowly than the data would dictate 32 Three dimensions for public perception of risk (Slovic, 1987) Dread risk – lack of control, catastrophic potential Unknown risk – risks that are unobservable Magnitude of risk – number of people exposed to it 33 Maintain accurate records – minimize primacy and recency effects Beware of wishful thinking – wishing for positive outcomes Disaggregate compound events into simple events 34 What is correlation? What is causation? Are they the same? 35 What is correlation? Degree of covariation between two variables What is causation? The outcome of one event resulting in the outcome of another event Are they the same? No – a common mistake made by many market researchers 36 Illusory - People can “see” a correlation between objects based on the objects semantic similarities, even when no correlation exists Invisible – People fail to see a correlation even when it exists – our expectations of visible patterns causes us to miss some strong but unexpected patterns 37 Einhorn and Hogarth, 1986 Correlation need not imply causal connection Causation need not imply a strong correlation Some people believe that causation implies correlation – they called it “causalation” 38 How people make causal attributions (Kelley, 1967) Three main variables to explain behavior The person The entity – feature of the situation The time – feature of the occasion Based on three sources of information Consensus, distinctiveness, and consistency 39 Sometimes people ignore base rate information Sometimes people focus on salient, available, or vivid information Fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1958) is that people’s behaviors tend to swamp all other situational variables 40 When faced with a successful outcome, people are more likely to accept responsibility and take more credit for the outcome When faced with an unsuccessful outcome, people are more likely to attribute blame to others Ego-centric biases – married couple example Positivity effect – attribute positive behaviors to dispositional factors and negative behaviors to situational factors 41