historyofenglish - Arizona State University

advertisement

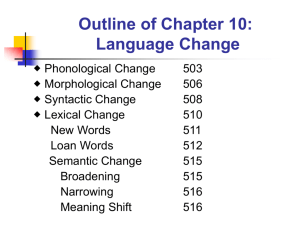

HISTORY OF ENGLISH See also “Semantic Gaps and Sources of New Words” by Don L. F. Nilsen and Alleen Pace Nilsen 1 HISTORY OF ENGLISH BEFORE ENGLAND 2 FOUR MAJOR LANGUAGE FAMILIES SINO-TIBETAN e.g. Mandarin Chinese FINNO-UGRIC e.g. Finnish, Hungarian, Estonian, etc. HAMIDO-SEMITIC e.g. Arabic and Hebrew INDO-EUROPEAN e.g. Romance, Germanic, Balto-Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and Celtic NOTE: GIVE OTHER LANGUAGE FAMILIES PLUS EXAMPLES: 3 INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES ROMANCE French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish BALTO-SLAVIC Bulgarian, Croation, Czech, Macedonian, *Old Church Slavonic, Polish, Russian, Serbian INDO-IRANIAN *Avestan, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Pashto, Persian, Urdu, CELTIC Breton, Cornish, Irish, Scots Gaelic, Welsh GERMANIC Afrikaans, Danish, Dutch, English, Flemish, German, Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, Yiddish 4 *PROTO INDO EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 522) 5 SOUND CHANGES BEFORE ENGLISH ABLAUT UMLAUT FIRST CONSONANT SHIFT (GRIMM’S LAW) SECOND CONSONANT SHIFT (TO DISTINGUISH HOCH DEUTCH FROM PLATT DEUTCH) 6 ABLAUT begin-began-begun break-broke-broken choose-chose-chosen come-came-come eat-ate-eaten fly-flew-flown sing-sang-sung 7 UMLAUT child-children goose-geese man-men mouse-mice woman-women 8 GRIMM’S LAW /bh/, /dh/, /gh/ => /b/, /d/, /g/ /b/, /d/, /g/ => /p/, /t/, /k/ /p/, /t/, /k/ => /f/, /Θ/, /h/ (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 510-511, 513) 9 GRIMM’S LAW (Herndon 413) 10 GRIMM'S LAW 1st GERMANIC CONSONANT SHIFT /b/ => /p/: bursa-purse, labial-lip /d/ => /t/: decade-ten, dozen-twelve, dent-tooth, duet-two /g/ => /k/: agriculture-acre /p/ => /f/: pedestal-footnote, padre-father, plate-flat, pyre-fire /t/ => /θ/: tricycle-three /k/ => /h/: courage-hearty, corn-horn, canis-hound (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 510-511, 513) 11 VERNER’S LAW “When the preceding vowel was unstressed, /f/ /θ/ /x/ underwent a further change to /b/ /d/ /g/.” (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 513) 12 nd 2 GERMANIC CONSONANT SHIFT: HIGH/LOW GERMAN penny-pfennig too-zu water-wasser 13 INDO-EUROPEAN NUMBERS ENGLISH: SPANISH: GERMAN: FRENCH: PERSIAN: one uno eins un yek two dos zwei deux do three tres drei trois seh four quatro fier quatre chahar five cinqo funf cinque panj (FRH [2011] 535) 14 HISTORY OF ENGLISH IN ENGLAND 15 499-1066: Old English 1066-1500: Middle English 1500-Today: Modern English 499: Saxons invade Britain 6th Century: Religious Literature 8th Century: Beowulf 1066: Norman Conquest 1387: Canterbury Tales 1476: Caxton’s Printing Press 1500: Great Vowel Shift 1564: Birth of Shakespeare (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2007] 462) 16 GREAT ENGLISH VOWEL SHIFT (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 493-494) 17 SOUND CHANGES IN ENGLISH 1. Great English Vowel Shift 2. Intervocalic Fricatives become contrastive (phonemic) 3. Loss of Vowels in Unstressed Syllables (Suffixes) 4. Loss of Duals 5. Number Becomes Intimacy (thou, thee, thy, thine, ye, you) 6. Loss of Verb Endings (-est, -eth) 18 Great English Vowel Shift A: bāt => boat, nāme => name E: mē => me, hē => he, wē => we, gēs => geese I: wīs => wise, ic => I, mīn => my, þīn => thine, mīs => mice O: ēow => you, gōs => goose U: þū => thou, mūs => mouse (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 493-494) 19 Intervocalic Fricatives become contrastive (phonemic) bath vs. to bathe calf vs. to calve half vs. to half house vs. to house lath vs. lathe safe vs. to save teeth vs. to teethe use vs. to use (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2007] 465) 20 Note that before English root syllables became stressed and English suffixes lost their stress and became lost, Old English was a very highly inflected language. In fact, at that time it was a synthetic language (with many inflections) rather than an analytic language (with prepositions and auxiliaries instead of suffixes). Here is an overview of Old English inflections. Contrast it with Modern English, but don’t sweat the details. 21 Loss of Vowels in Unstressed Syllables (Suffixes) Nominative: bātas (boat) stān (stone) Accusative: bāta stānes Genitive: bātas stāne Dative: bātum stāne Instrumental: bātum stān (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 494) 22 SINGULAR ADJECTIVES, NOUNS & PERSONAL PRONOUNS ADJ: N: PERSONAL PRONOUNS: 1st 2nd 3rd Nom: wīs bāt ic þū hē/hit/hēo Gen: bātes mīn þīn his/his/hiere bāte mē þē him/him/hiere bāt mē þē hine/hit/hit bāt mē þē hine/hit/hit Dat: Acc: Inst: wīses wīsum wīsne wīse 23 DUAL ADJECTIVES, NOUNS & PERSONAL PRONOUNS ADJ: N: PERSONAL PRONOUNS: 1st 2nd Nominative: wit git Genitive: uncer incer Dative: unc inc Accusative: unc inc 24 PLURAL ADJECTIVES, NOUNS & PERSONAL PRONOUNS ADJ: N: PERSONAL PRONOUNS: 1st 2nd 3rd Nom: wīse bātas wē gē hie/hie/hie Acc: wīse bāta ēow hie/hie/hie Gen: wīsra bātas ūre ēower hiere/hiere/hiere Dat: wīsum bātum ūs ēow him/him/him Inst: wīsum bātum ūs ēow him/him/him ūs 25 VERBS IND: SINGULAR: 1st drīfe 2nd drīfest 3rd drīfeþ SUBJ: drīfe drīfe drīfe drīf drāf drīfe drāf PLURAL: drīfaþ drīfen drīfaþ VERBALS: INFINITIVE: GERUND: PARTICIPLE: IMP: PAST TENSE: drīfon drīfan tō drīfenne drīfende SUPPLETIVE VERBS, which come from two different paradigms: ēom, eart, is, sindon, wæs, wære, wæron NOTE: “go” comes from the “to go” paradigm; but “went” comes from the “to wend” paradigm 26 OLD ENGLISH: “The Lord’s Prayer” Fæder ure, þou þe eart on heofonum, si þin name gehalgod. Tobecume þin rice. Gewurþe þin willa on eorþan swa swa on heofenum. Urne gedæghwamlican hlaf syle us to dæg. And forgyf us ure gyltas, swa swa we forgyfaþ urum gyltendum. And ne gelæd þu us on costnunge, ac alys us of yfele. Soþlice. (Roberts [2009]: 76) 27 MIDDLE ENGLISH, from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote The droght of March hath perced to the roote… When April with its sweet showers The drought of March has pierced to the root…. (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 489, 496) 28 MIDDLE ENGLISH, from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales Ther was also a nonne, a Prioresse, That of hir smyling was ful symple and coy, Hir gretteste oath was but by Seinte Loy, And she was cleped Madame Eglentyne. Ful wel she song the service dyvyne, Entuned in hir nose ful semely. And Frenshe she spak ful faire and fetisly After the scole of Stratford-atte-Bowe, For Frenshe of Parys was to hir unknowe. (Roberts [2009]: 90) 29 EARLY MODERN ENGLISH: Shakespeare’s Hamlet A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm. (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2007] 462) 30 THE KING’S ENGLISH Name the ruler who settled: Charleston Georgia Jamestown Louisiana North and South Carolina Virginia and West Virginia Williamsburg 31 TODAY: ENGLISH AS A WORLD LANGUAGE In Hong Kong you can find a place called the “Plastic Bacon Factory.” In Naples, there is a sports shop called “Snoopy’s Dribbling,” while in Brussels there is a men’s clothing store called “Big Nuts,” which has a sign saying “SWEAT—690 FRANCS.” This was for a sweatshirt. 32 In Japan you can drink “Homo Milk” or “Poccari Sweat” (a popular soft drink, eat some chocolates called “Hand-Maid Queer-Aid,” or go out and buy some “Arm Free Grand Slam Munsingswear.” (Nilsen & Nilsen 164) (from Bill Bryson’s The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way) 33 ANACHRONISM # 1: Pease porridge hot. Pease porridge cold. Pease porridge in the pot nine days old. (Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2007] 476) EXPLANATION: On the first day of a march, prisoners used to be served hot pea soup. On the second day they were served cold pea soup. And on the ninth day of the march they would be served pea soup that had been in the pot for nine days. 34 ANACHRONISM # 2 Bob Newhart does a sketch in which Sir Walter Raleigh telephones the West Indies Company in London. He was reporting on his voyage to the New Land of America. Since Sir Walter Raleigh is on the telephone, we can only hear one side of the conversation: 35 “What is it this time, Walt? You got another winner for us do you? Tobacco? What’s tobacco, Walt? It’s a kind of leaf and you bought 80 tons of it? … You take a pinch of tobacco and shove it up your nose and it makes you sneeze. I imagine it would, Walt…”. The skit ends with, “You’re going to have a tough time telling people to stick burning leaves in their mouth.” (Nilsen & Nilsen 31) 36 Web Site History of English: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aLdQ4DUnnw4&feature=fvw History of Five Religions: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-sIF78QYCI 37 References: Aitchison, Jean “Language Change: Progress or Decay? (Clark, Eschholz & Rosa, [1998]: 431-441). Bryson, Bill. The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way. New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990. Clark, Virginia, Paul Eschholz, and Alfred Rosa, eds. Language: Readings in Language and Culture, 6th Edition. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1998. Eschholz, Paul, Alfred Rosa, and Virginia Clark, eds. Language Awareness: Readings for College Writers, 10th Edition. Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2009. Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Oxford, England: Blackwell, 2001. 38 Falk, Julia. “To Be Human: A History of the Study of Language” (Clark, Eschholz & Rosa [1998]: 442-476). Fromkin, Victoria, Robert Rodman, and Nina Hyams. “Language Change: The Syllables of Time.” An Introduction to Language, 9th Edition. Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2011, 488-539. Herndon, Jeanne H. “Comparative and Historical Linguistics” (Clark, Eschholz & Rosa [1998]: 411-419). Moore, Samuel and Albert Marchwardt. Historical Outlines of English Sounds and Inflections. Ann Arbor, MI: Wahr, 1969. Nilsen, Alleen Pace. “Changing Words in a Changing World.” Living Language. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1999, 427-473. 39 Nilsen, Alleen Pace. “Technology and Language Change.” Living Language. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 1999, 379-426. Nilsen, Alleen Pace, and Don L. F. Nilsen. Encyclopedia of 20th Century American Humor. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000. Ohio State University Files. “The Family Tree and Wave Models” (Clark, Eschholz & Rosa [1998]: 416-419). Roberts, Paul “A Brief History of English” (Clark [1998]: 420-430, Eschholz, Rosa & Clark [2009]: 84-93]). van Gelderen, Elly, A History of the English Language. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins, 2006. 40

![Fromkin Rodman Hyams [2011] 434-435](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/009909054_1-3e8d1ff35415002ed881cb701b9292e6-300x300.png)