Project Identification Form (PIF) Project Type: Full

advertisement

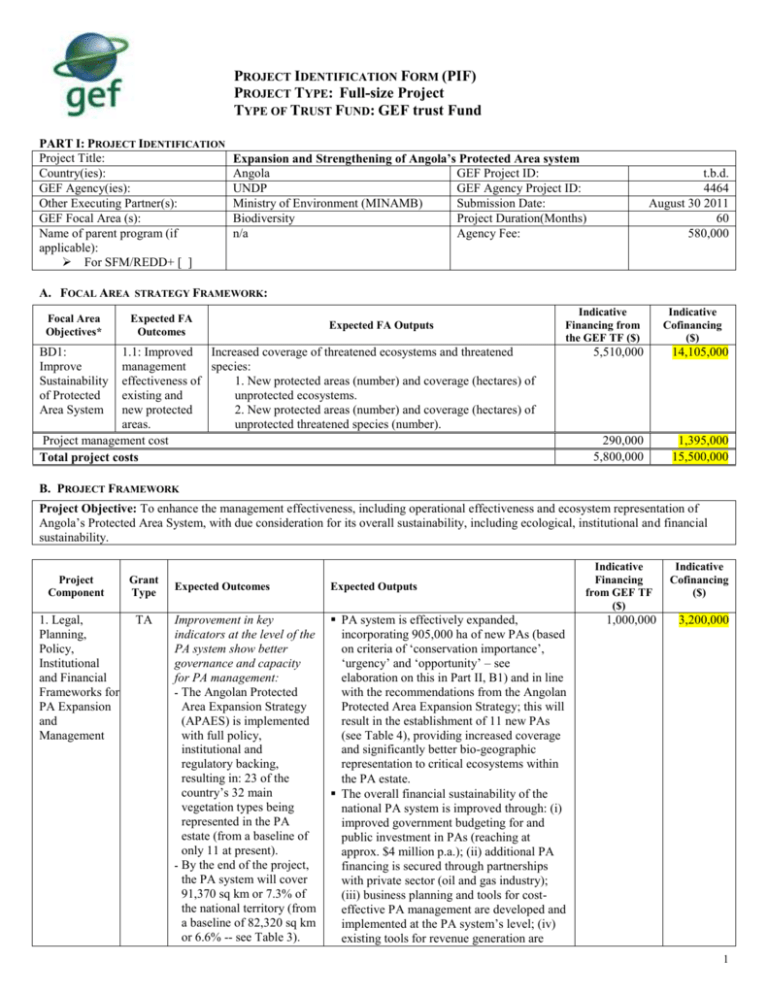

PROJECT IDENTIFICATION FORM (PIF) PROJECT TYPE: Full-size Project TYPE OF TRUST FUND: GEF trust Fund PART I: PROJECT IDENTIFICATION Project Title: Country(ies): GEF Agency(ies): Other Executing Partner(s): GEF Focal Area (s): Name of parent program (if applicable): For SFM/REDD+ [ ] Expansion and Strengthening of Angola’s Protected Area system Angola GEF Project ID: UNDP GEF Agency Project ID: Ministry of Environment (MINAMB) Submission Date: Biodiversity Project Duration(Months) n/a Agency Fee: t.b.d. 4464 August 30 2011 60 580,000 A. FOCAL AREA STRATEGY FRAMEWORK: Focal Area Objectives* Expected FA Outcomes Expected FA Outputs Indicative Financing from the GEF TF ($) BD1: Improve Sustainability of Protected Area System 1.1: Improved Increased coverage of threatened ecosystems and threatened management species: effectiveness of 1. New protected areas (number) and coverage (hectares) of existing and unprotected ecosystems. new protected 2. New protected areas (number) and coverage (hectares) of areas. unprotected threatened species (number). Project management cost Total project costs Indicative Cofinancing ($) 5,510,000 14,105,000 290,000 5,800,000 1,395,000 15,500,000 B. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: To enhance the management effectiveness, including operational effectiveness and ecosystem representation of Angola’s Protected Area System, with due consideration for its overall sustainability, including ecological, institutional and financial sustainability. Project Component Grant Type 1. Legal, Planning, Policy, Institutional and Financial Frameworks for PA Expansion and Management TA Expected Outcomes Expected Outputs Improvement in key indicators at the level of the PA system show better governance and capacity for PA management: - The Angolan Protected Area Expansion Strategy (APAES) is implemented with full policy, institutional and regulatory backing, resulting in: 23 of the country’s 32 main vegetation types being represented in the PA estate (from a baseline of only 11 at present). - By the end of the project, the PA system will cover 91,370 sq km or 7.3% of the national territory (from a baseline of 82,320 sq km or 6.6% -- see Table 3). PA system is effectively expanded, incorporating 905,000 ha of new PAs (based on criteria of ‘conservation importance’, ‘urgency’ and ‘opportunity’ – see elaboration on this in Part II, B1) and in line with the recommendations from the Angolan Protected Area Expansion Strategy; this will result in the establishment of 11 new PAs (see Table 4), providing increased coverage and significantly better bio-geographic representation to critical ecosystems within the PA estate. The overall financial sustainability of the national PA system is improved through: (i) improved government budgeting for and public investment in PAs (reaching at approx. $4 million p.a.); (ii) additional PA financing is secured through partnerships with private sector (oil and gas industry); (iii) business planning and tools for costeffective PA management are developed and implemented at the PA system’s level; (iv) existing tools for revenue generation are Indicative Financing from GEF TF ($) 1,000,000 Indicative Cofinancing ($) 3,200,000 1 Project Component Grant Type Expected Outcomes Improved financial sustainability of national PA system: by project end, scores of the PA Finance Scorecard increase by 20% and the annual financing gap for optimal expenditure scenarios decreases by 50% vis-a-vis the baseline) - Improved capacity for PA system management at the systemic, institutional and individual levels: this is evidenced by an increase of 20% in the overall results of the Capacity Development Scorecard Expected Outputs - 2. PA Rehabilitation and Management models at existing PAs Inv / TA PA management effectiveness assured in 3 priority national parks (target PAs); this mitigates direct threats to biodiversity over an area of at least 18,460 sq km including varied vegetation groups (forest/savanna mosaics, Acacia/Adansonia savannas and thickets, edaphic grasslands, swamps and Miombo woodlands and savannas), as evidenced by: - Improved management capacity in target PAs for general management, PA & business planning and community engagement, measured by 30% increases in METT scores improved (e.g. PA entry fees) and new ones tested (e.g. concessions, licenses and levies); (v) revenue retention within the PA system is ensured; (vi) combining all of the above elements, the financing needs of an enlarged PA system are projected over 10 years (“PA financing roadmap”) and a multi-faceted strategy for meeting those needs enters into fully-fledged implementation by the project’s year 3. A roadmap for fulfilling the management needs of the 11 new PAs and for the further expansion of the PA estate (in line with the recommendations from the CBD’s Aichi Target 11) is agreed upon, with its funding needs duly built in the 10-year ‘PA finance roadmap’. Central level PA management capacity is significantly enhanced: (i) National Institute of Biodiversity and Conservation Areas (INBAC) vested with a strong and clear legal mandate for the establishment and management of protected areas; (ii) it is able to strategize, plan, monitor its results and learn; (iii) it has improved capacity to attract funding and enter into useful public- private community partnerships to manage protected areas; (iv) it has an adequate staff complement with key HR skilled in protected area planning and management (with special focus on PA finance); and (v) it is equipped to fulfil its institutional mandate and has access to the necessary information and knowledge for the purpose. PA site rehabilitation and operationalisation works completed at Quiçama, Cangandala and Bicuar National Parks (NPs): (i) staffing the PAs; (ii) building, rehabilitating and maintaining infrastructure; (iii) procuring and maintaining equipment; and (iv) rendering, and outsourcing certain services (e.g. wildlife monitoring and research). PA management plans for Quiçama, Cangandala and Bicuar NPs are operationalised, and provide for: (i) zonation of PAs for strict protection, tourism, and sustainable use of natural resources by PA adjacent communities; (ii) the regulation and management of natural resources within PAs and adjacent areas (including sustainable use of resources by communities); (iii) fire management system emplaced; (iv) effective law enforcement governing wildlife poaching; wood harvesting and other natural resource use; and (v) PA governance, including Indicative Financing from GEF TF ($) 4,510,000 Indicative Cofinancing ($) 10,905,000 2 Project Component Grant Type Indicative Financing from GEF TF ($) Expected Outcomes Expected Outputs against baseline assessed at project initiation - Critical habitats within target PAs actively managed and the impact of the intervention is demonstrated by improved ecological indicators (e.g. vegetation cover, incidence of fire, status of indicator species) - Populations for selected taxa within target PAs show improved ecosystem management (species, baseline, targets and measurement methods t.b.d. during PPG) - Land use zonation within PAs and in surrounding areas is effective on the ground by project end (as independently assessed) participation of PA adjacent communities in PA management, and the development of conflict resolution mechanisms; Systems and tools for monitoring key PA management functions and outcomes are operational in Quiçama, Cangandala and Bicuar NPs: (i) METT assessments become widespread tool for gauging the effectiveness of PA functions and their management; (ii) long-term ecological monitoring systems are in place for targeted species and ecosystems, establishing thresholds for resource use and informing PA management; (iii) monitoring enforcement of regulations (including effectiveness of surveillance, interception, prosecution). The participation of PA adjacent communities in conservation compatible livelihoods activities (including employment opportunities generated by PA rehabilitation works) ease up the pressure on PA resources. Project management Cost Total project costs Indicative Cofinancing ($) 290,000 5,800,000 1,395,000 15,500,000 C. INDICATIVE CO-FINANCING FOR THE PROJECT BY SOURCE AND BY NAME IF AVAILABLE, ($) Sources of Co-financing for baseline project* National Government GEF Agency Bilateral Aid Agency (ies) Private Sector CSO Total Co-financing Name of Co-financier Project Government Contribution GEF Agency - UNDP Angola Bilateral Aid Agencies engaged in BD management Private Sector companies engaged in supporting conservation International, national and local NGOs and Foundations Type of Cofinancing** Grant Grant Grant In-kind Grant and In-kind Amount ($) 10,000,000 2,000,000 1,000,000 2,000,000 500,000 15,500,000 D. GEF RESOURCES REQUESTED BY AGENCY (IES), FOCAL AREA(S) AND COUNTRY(IES)1 GEF TYPE OF AGENCY TRUST FUND UNDP GEF TF Total GEF Resources 1 2 FOCAL AREA* Biodiversity Country name/Global Angola Project amount (a) 5,800,000 5,800,000 Agency Fee (b)2 580,000 580,000 Total c=a+b 6,380,000 6,380,000 In case of a single focal area, single country, single GEF Agency project, and single trust fund project, no need to provide information for this table Please indicate fees related to this project as well as PPGs for which no Agency fee has been requested already. PART II: PROJECT JUSTIFICATION A. DESCRIPTION OF THE CONSISTENCY OF THE PROJECT WITH: A.1.1. THE GEF FOCAL AREA STRATEGIES: The proposed project advances GEF Biodiversity Objective 1 “Improve Sustainability of Protected Area Systems” (BD1) and specifically Outcome 1.1 “Improved management effectiveness of existing and new protected areas”. Currently, the Angolan PA system has two main weaknesses: first, the system falls short in terms of its bio-geographic representation—with several terrestrial ecosystems 3 currently under-represented1; second, constituent PAs in the current system have sub-optimal management effectiveness and are not effectively mitigating the threats to ecosystems, flora and fauna. The project is designed to address both sets of weaknesses simultaneously. It will improve ecosystem representation in the PA system and it will strengthen PA management operations at key sites, as both sets of interventions are needed. This will be underpinned by investments at the system’s level, to strengthen the institutional foundations and financing framework for PA management. The project will increase the coverage of terrestrial PAs in Angola to include 23 of the 32 mapped vegetation types (up from a current 11 vegetation types covered). As a result, the species-rich moist lowland, escarpment and montane forests will be incorporated into the PA system, among other unique habitats that are currently not protected. These ecosystems stand to be lost or degraded unless prompt action is taken to bring them under protection. The expansion will add 9,050 sq km to the existing PA estate, increasing the coverage from approximately 6.6% to 7.3% of the national territory. Through onthe-ground interventions planned under Component 2, the project will enhance the capacity of the PA authority to deliver PA functions, including management planning, monitoring, surveillance of malpractices and law enforcement. It will also address the needs of PA adjacent communities, for example by managing human-wildlife conflicts and developing activities that generate local socio-economic benefits. This is an opportune moment to strengthen Angola’s PA system as a whole, ensuring that it effectively fulfils its purpose as a storehouse of protected biodiversity while safeguarding natural capital vital to development (including ecosystem services, such as water provisioning, and future tourism development potential). Although the two-pronged objective, targeting both PA expansion and rehabilitation, may seem ambitious at this juncture, a combined approach is critical given the current reality. Firstly, it is necessary to increase PA management effectiveness of existing parks by taking immediate, pragmatic action on-the-ground to address threats. This should not be postponed. Secondly, the areas identified for PA expansion have been selected based on the following criteria: (1) importance (uniqueness, irreplaceability); (2) urgency (vulnerability, threat); and (3) opportunity (low societal cost of setting land aside for conservation). Notably, the opportunity cost attached to land in Angola is increasing. There is currently a unique window of opportunity to establish the planned new protected areas—which is likely to be foreclosed in the future. Angola’s economy is growing fast; although the country faces severe social and economic problems, and remains a LDC, the fiscal situation is improving. The Government is preparing to increase investment in PA management, to cover investment and recurrent costs. There is a need to develop institutional capacities and know-how for PA management and cost effective management solutions, to ensure that these investments yield solid environmental benefits. The project will address this need and by doing so, it will enhance the sustainability of the PA system. A.2. NATIONAL STRATEGIES AND PLANS OR REPORTS AND ASSESSMENTS UNDER RELEVANT CONVENTIONS, IF APPLICABLE: The Government is requesting GEF funding for this project under the GEF V financing window, to advance its national policy priorities for biodiversity conservation. The project is designed to implement key elements of Angola’s National Environment Management Plan (NEMP, approved in 2009), its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP, approved in 2006), and its National Protected Areas Expansion Strategy (currently under development, based on a 2006 evaluation of the National PA System carried out by MINAMB, and an earlier review carried out in collaboration with IUCN). 2 In particular the project is in line with the NBSAPs’ Strategic Area C. ‘Biodiversity Management in Protected Areas’; E. ‘The Role of Communities in Biodiversity management’; F. ‘Institutional Strengthening’; and H. ‘Management, Coordination and Monitoring’. The government of Angola recognizes its commitments as signatory of the CBD and has undertaken in its Medium Term Economic and Social Development Plan (2009-2013) to promote sustainable development and economic growth while systematically protecting Angola’s biodiversity and natural resources. In particular, the government has shown a clear commitment to expanding the PA system, the Minister for Environment recently having set a target of expanding by 2020 the PA system to cover 15% of the national territory. By increasing the area of the PA estate and strengthening PA management effectiveness, this project will make a significant contribution to realisation of the revised CBD Program of Work on PAs.3 B. PROJECT OVERVIEW: B.1. DESCRIBE THE BASELINE PROJECT AND THE PROBLEM THAT IT SEEKS TO ADDRESS: Global biodiversity significance. Angola is blessed with an exceptionally rich biodiversity endowment. With a land surface of 1,246,000 sq km, it boasts the greatest diversity of biomes and ecoregions in any single African country—from the desert biome of the southwest, through arid savannas of the south, extensive miombo woodlands of the interior plateau, to the rainforests of Cabinda, Zaire, Uige and Lunda Norte Provinces. Relict Afro-montane forests of considerable bio-geographic importance occur in isolated valleys of the high mountains in Huambo, Cuanza Sul, Huila and Benguela provinces (Table 2). According to surveys undertaken in the 1970s, more than 25% of Angola is covered by a mosaic of moist forest and tall grass savannas, of which a small percentage (2.2%) is moist evergreen forest. 53% of the landscape is covered by miombo woodlands and savannas, and 11% by arid mopane and acacia savannas and dry forests (Huntley 1974). The sheer size of the country and its inter-tropical geographical location result in high faunal and floral 1 This project will not deal with the challenges of providing adequate coverage to marine ecosystems in the PA system. A new policy paper titled ‘Strategic Plan for the Protected Area Network’ outlines the core ideas behind Angola’s PA expansion strategy. It is being prepared for wide discussion. It will eventually be submitted for approval by the Council of Ministers. The Plan will amongst other things take into account PA finance considerations. 3 In particular, Para 1(a) and (b) of decision X/31, where in Parties have agreed to enhance coverage, quality and representativeness of PAs; Para 32 (a) wherein Parties have agreed to improve, diversify and strengthen PA governance types; Para 14 (a) and Target 11 wherein Parties agreed to take concerted efforts to integrate protected areas into wider landscapes and seascapes and sectors, in order to address anticipated climate change impacts and increase resilience to climate change. 2 4 diversity, displaying a reasonable level of endemism4. The rich bird fauna includes 915 species, while 266 freshwater fish species have been recorded. Accurate checklists for the country’s reptile and amphibian fauna are yet to be compiled, but at least 78 amphibian and 227 reptile species are known to occur. Over 6,650 species of plants have been recorded, including the unique Welwitschia mirabilis – a ‘living fossil’ representing one of the earliest known plant families. Also, the country harbours large mangrove forests (in the Congo, Dande, Cuanza and Cunene river estuaries) and has a 1,610 km shoreline along the biologically rich Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem. Threats to biodiversity. Angola’s terrestrial biodiversity, the focus of this project, faces growing threats linked to habitat / land use change and overexploitation of natural resources. Deforestation driven by agriculture, livestock rearing and domestic energy production (with 80% dependence on firewood and charcoal) has led to widespread degradation of forest ecosystems. The FAO estimated Angola’s deforestation rates in 2003 as being 0.2% per annum – a rate believed to have gone up since. The country’s once abundant large mammal fauna has been severely depleted, but scattered remnant populations of all 275 mammal species known from Angola have survived the heavy hunting pressure that occurred during the long civil war and can recover over the long-term with appropriate wildlife management measures.5 The Protected Area System. The Angolan PA estate is currently comprised of six national parks, one regional park, one strict nature reserve and five partial reserves, all established during colonial times. The surface area covered by the estate amounts to 82,320 sq km (Table 1). Management and oversight of the PA estate is the prime responsibility of MINAMB’s National Directorate for Biodiversity, which manages most of the sites directly6 counting on a small technical team and, in the case of terrestrial PAs, support from park wardens and forestry guards deployed by the Forestry Development Institute (IDF). The Institute is attached to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and Fisheries, and it is responsible for the management of forests and wildlife (e.g. issuance of logging and hunting permits). In turn, MINAMB is responsible for the management of the sites themselves (e.g. infrastructure, landscape management, control of access to sites). The combined operational budget of MINAMB and the Forestry Development Institute for PA management is currently less than $1-1.5 million per annum, one of the lowest PA budgets in Africa. As a result, PA management effectiveness is low and so is the overall national capacity for PA management (at the systemic, institutional and individual levels). Many of the areas listed in Table 1 lack up-to-date management plans and their infrastructure requires rehabilitation—in many cases having been destroyed during the war. Many sites have minimum personnel and equipment relative to their management needs. On a more positive note, the Government is in the process of establishing the new National Institute of Biodiversity and Conservation Areas (INBAC), which will assume operational responsibilities for PA management. Yet, much more is needed to raise the conservation effectiveness of Angola’s PA system. Pursuing this goal is a priority to the extent that biodiversity conservation has become a national priority, in part because of increasing recognition amongst policy makers of the importance of ecosystem goods and services to the economy. Table 1. The Protected Areas estate of Angola* Name Area, sq km Category Date of Centre of endemism Reference to vegetation establishment types in Table 3 Iona 15,150 National Park 1937 Karoo-Namib 21, 27, 28, 29 Cameia 14,450 National Park 1938 Zambezian 17, 31 Quiçama 9,960 National Park 1938 Zambezian 11, 23, 30 Luando 8,280 Strict Nature Reserve 1938 Zambezian 17, 18 Bicuar 7,900 National Park 1938 Zambezian 15, 18 Mupa 6,600 National Park 1938 Zambezian 15, 18, 20 Namibe 4,450 Partial reserve 1957 Karoo-Namib 27,28 Cangandala 630 National Park 1963 Zambezian 18 Chimalavera 150 Regional Park 1972 Karoo-Namib 27 Mavinga 5,950 Partial Reserve** 1966 Zambezian 25 Luiana 8,400 Partial Reserve** 1966 Zambezian 25 Bufalo 400 Partial Reserve 1974 Karoo-Namib 27 * Does not include hunting concessions or Coutadas. ** To be re-gazetted as national park (actual area is still under discussion). The Angolan PA system remains embryonic. It is not yet configured and capacitated at the systemic-institutional level and significant funding remains to be mobilised. As it is, individual sites fall short of effectively conserving globally significant biodiversity, which is under accelerating pressure from numerous human activities. Existing terrestrial PAs cover less than 6.6% of the land surface, and leave unprotected 21 out of the country’s 32 vegetation types. Quoting the 2006 NBSAP: “Of the estimated over 5.000 plant species that are believed to exist in the country (without mentioning the vast flora wealth of Cabinda Province), 1.260 are endemic – making Angola the second richest country in Africa in endemic plants. The diversity of mammals is also one of the richest on the continent, with 275 recorded species. Bird resources are diversified. Angola has 872 catalogued species. About 92% of the avifauna of southern Africa occurs in Angola.” 5 E.g. a small breeding group of the country’s national symbol, the Giant Sable antelope, believed for many years to be extinct, has recently been established in Cangandala National Park in Malange. This relict herd is being actively managed within a fenced area for reproduction and rehabilitation of the population with funding from the oil company Esso. The initiative is however limited to the capture and initial PA rehabilitation phase. 6 There are a few exceptions to direct management by MINAMB, such as parts of Quiçama managed by Kissama Foundation. 4 5 Context. Angola has a population of 16 million spread unevenly across the country. Most people live in urban centres in the provinces of Luanda, Huambo, Benguela, Bié and Cunene, while vast areas in Cuando Cubango are sparsely populated. The economy is growing rapidly, fuelled by the growth of the petroleum sector which has brought a ‘development bonanza’ to many parts of the country, but particularly to Luanda City. From the time of independence in 1975 to 2002, armed conflict caused over 1.5 million deaths, the displacement of an estimated 4 million refugees, and the destruction of infrastructure over extensive areas of the country. As a consequence of the war, poverty is a serious problem with 68% of Angolans living below the poverty line of US$1.70 per capita per day (95% of the rural dwellers, 57% of the urban ones). Since the end of the war in 2002, Angola has undergone profound socio-economic transformations, in particular (i) from a situation of war, destruction and dislocation of its population, to a situation of peace, national reconstruction and resettlement; (ii) from a centralized economy to a process of developing a market economy; (iii) from a centralized governance regime to a regime of more devolved power, and to one of increased provincial and municipal autonomy; and (iv) from the use of colonial era legislation to a new body of laws – including extensive reform and improvement of environmental legislation. At the time of proclamation in the 1930s and 1950s, most of Angola’s PAs had small resident human populations. As a consequence of the war, the displacement of civilian populations has led to the further occupation of many PAs, a situation that cannot be easily reversed. Most settlements are however localized, so adequate zonation and land use planning within PAs and adjacent areas have good chances of providing a mechanism for reducing negative impacts of irregular occupation, while catering to socio-economic development. The baseline project. The government’s annual budgetary allocation for the ‘environment sector’ in general is substantial—reaching nominally some $50 million in 20117. This includes a wide range of sub-sectors of environmental management: natural resource management, water resource management and management of extractive industries. Moreover, this public investment is managed through several line ministries in charge of several sectors and sub-sectors (environment, agriculture, fisheries, land use planning to name a few). State-lead investments provide funding to a number of governmental programmes that seek to manage land-based, coastal, riverine and inland waters ecosystems, but also to protect aquifers, combat pollution and counteract land degradation. In November 2010, the Environment Fund was created. Although it remains to be fully capitalised, the prospects are promising. In addition, the government’s specific investment in conservation is likely to increase in the next few years, e.g. through the new Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier programme or “KASA”, which will lead to the establishment of a large transfrontier conservation area in a vast zone straddling Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Furthermore, the expected approval of the ‘Strategic Plan for the Protected Area Network’ is also bound to trigger and attract increased investments in the rehabilitation of protected areas throughout the country (likely from 2012 on). The mentioned Strategic Plan clearly states: “The Government of Angola recognizes the importance of conserving biodiversity and the designation and protection of areas of ecological importance [...]”. It further indicates that the government “should establish a national and permanent budgetary allocation to ensure adequate and reliable finance to the planning, development, establishment, creation, implementation, management, protection, monitoring and routine maintenance of the National Network of Conservation Areas.” Besides public investments, other baseline investments for this project include a number of other programmes and projects supporting environmental management in general. The African Development Bank provides funding to an ongoing project to support the environment sector (ESSP), aimed at developing national capacities for environmental management. Several conservation initiatives are underway, such as the efforts to enhance the conservation status of the Giant Sable at Candangala National Park (supported by Esso and other corporate players) and the management of a small fenced area of Quiçama National Park (under the leadership of the Kissama Foundation – a national NGO). On-going PA rehabilitation initiatives are planned in some PAs, for instance Bicuar National park, which is receiving funding from Deutsche Bank in partnership with a Spanish firm, though it remains limited in terms of duration and scope. These PA initiatives contribute in general to the conservation agenda, but are largely site-based and project-driven. Compared to the overall level of investments in the environment sector, specific investments in protected area management (including government, private sector, NGO and donor financed) remain modest—less than $1.5 million p.a. These investments also lack coherence, in terms of addressing PA management priorities. There is thus a need to reconfigure investments and scale them up to address PA management needs. The proposed long-term solution. The long term conservation solution is to create a functional, representative and sustainable system of protected areas that effectively buffers biodiversity from threats—current and future. A number of barriers stand in the way of realising this proposed solution: Barriers Inadequate capacity at the systemic level for PA management: the policy, legal, institutional and Elaboration The relatively weak state of knowledge available on the status of Angola’s biodiversity is well known. An adequate overarching strategy for managing and expanding Angola’s PA system would need to rely on improved knowledge and appropriate data systems. For the terrestrial biome, this barrier was initally overcome by focusing on existing studies based on vegetation types (see Table 2, 3 and 4) and defining, through the initial PA expansion strategy, priority areas for gazettal, which were incorporated in the draft for the ‘Strategic Plan for the Protected Area Network’. Both the PA Includes national programmes under the budget items ‘environment’ (in general) plus ‘development and sustainable management of forest resources’. Another $100 million is reported allocated to ‘combating environmental degradation’ and pertains primarily to investments in erosion control and pollution. (Source: Ministry of Finance's website, Summary of current expenses per programme 2011.) 7 6 financial frameworks for the management of the PA system have deficiencies that need to be addressed Existing PAs display low level of management effectiveness and PA institutions and staff have deficient capacity to manage PA units as effective centres of biodiversity conservation. expansion strategy and the rehabilitation of key national parks are part and parcel of the mentioned new Strategic Plan. The government will press ahead with new legislation establishing new areas in an effort to address deficiencies in the bio-geographic representation of ecosystems in the PA estate. However, at the PA system’s level, there are a number of barriers still to be overcome for ensuring the success of such initiative. At the heart of all PA systemic issues, is the issue of finance. The general level of investment in PA management is currently low, though on the increase. Yet, there is the need to ensure that government budgeting for the PA systems is adequate, equitable, well targeted, and that it is sustained over time. There is also the need to ensure that this investment is catalytic, e.g. that it will attract and leverage other investments, say from private sector, NGOs, communities, etc. Deficiencies in revenue generation from PAs and for the PA system are equally part of the finance barrier and need to be addressed. While tools could be explored for the purpose, PA investment needs and trends, as well as the prospects for revenue generation, remain to be assessed. On the legal front, further delays in the approval and implementation of the Law on Forests, Wildlife and Protected Areas could undermine efforts to expand the PA estate and operationalise management within existing PAs. Furthermore, the current PA and forest management practices do not adequately address the interests and objectives of local populations. The legal and policy elements for their participation in PA management remain to be enshrined in new legislation. At the institutional front, clarifying the mandate and attributions of different government bodies, in particular, those of the new INBAC and of IDF for the delivery of PA functions (planning, monitoring, enforcement and the like), is essential. This may become a barrier if the restructuring process becomes lengthy, contentious and if it does not ensure the creation of critical technical and managerial posts and budget lines to ensure the effective operation of PA institutions. Also, a key barrier for the success of a strategy that both seeks to expand the PA estate and rehabilitate existing PAs is to ensure that the human resources assigned to it are both sufficient in number and have the adequate capacity to fulfil their role. The rehabilitation of the existing PAs is a priority within the PA strengthening agenda. The process must start with a realistic assessment of the baseline situation for each PA using METT and similar tools. These have not been used in Angola before. A comprehensive PA infrastructure assessment and assets survey also remains to be carried out. Besides the general lack of management and operational planning, a key barrier to a more effective PA estate is that many of its units are understaffed. Existing staff have received limited training in essential PA management functions, and none in critical topics such as development of revenue-generating schemes, financial planning and management, or outreach to and collaboration with local communities within and bordering PA units. Despite the potential for activities like photo safaris, bird-watching, and combined cultural-ecological visits, PAs in Angola have yet to pursue the development of ecotourism, exploring, where applicable, the involvement of private sector investors in PA infrastructure development—some pilot experiences exist, however. Furthermore, there are good prospects for engaging partnerships in the management and support to PAs (e.g. with foundations, NGOs, academia and investors). Yet, a key barrier to it is the deficient capacity to create and maintain these partnerships. Also, several of the national parks do not count on management boards, where key stakeholders could more effectively participate in PA management. Area surveillance, enforcement, fire control and ecological monitoring are carried in ad hoc and non-systematic manner. Finally, although the knowledge and information basis on different human settlements within and around PAs is largely insufficient and incomplete, it is known that local populations are neither organized nor trained in sustainable resource management & conservation in order to realize benefits from the establishment, rehabilitation and management of protected areas. B. 2. INCREMENTAL /ADDITIONAL COST REASONING: DESCRIBE THE INCREMENTALACTIVITIES REQUESTED FOR GEF FINANCING AND THE ASSOCIATED GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS (GEF TRUST FUND) TO BE DELIVERED BY THE PROJECT: The Government of Angola is requesting GEF support through this project to remove, in an incremental manner, the existing barriers to the management effectiveness of the Angolan PA system. The project's Goal is to conserve Angola's globally significant biodiversity by strengthening PA management effectiveness and improving the ecosystem representation within the PA system. Two components are planned: Component 1) National PA System Governance Framework (Legal, Policy, Planning, Institutional and Financial) for Protected Area Management. The project will address PA management gaps in terms of the overarching legal, policy and institutional frameworks, and also establish a road map and take measures to secure necessary government budgetary appropriations and other funds for the PA system. The project will also facilitate the approval of the Law on Forests, Wildlife and Protected Areas, which will clearly define, without overlaps, roles, responsibilities and institutional mandates with respect to PA management. The project will support the institutional development of INBAC (i.e. beyond the mere decree that creates the new body). This pertains to adequately staffing and equipping the new institute. MINAMB/INBAC staff will be trained and a National PA Training & Certification Plan will be developed and executed in order to address the most pressing PA management capacity gaps. 8 This will be done in close collaboration with related projects, such as the UNDP/GEF’s National Biodiversity Project (with focus on Iona) and the African Development Bank’s Environmental Sector Support Project (ESSP), which is facilitating formal tertiary and technical training of MINAB’s staff, including in areas such as biodiversity and natural resource management. The project will also contribute towards implementation of the PA expansion programme through the proclamation of 11 new PAs in critically important lowland, escarpment and montane forests. The fast-tracked gazettal of new PAs will be achieved through the development of legal texts to proclaim new areas and, where needed, 8 This may also apply to IDF, depending on the resulting institutional framework enshrined in the Law on Forests, Wildlife and Protected Areas to be approved. 7 targeted demarcation actions on the ground, with support from provincial and local authorities among others. Finally, a phase II of the APAES will be outlined and agreed upon, in line with CBD Aichi Target 11. 9 The approval of APAES Phase II will also provide a framework for fulfilling the management needs of the 11 new PAs established under this component and mobilise the funding for it. Component 2) Rehabilitation and management models at four pilot PAs. The project will support the rehabilitation of the Quiçama, Cangandala and Bicuar10 National Parks, which collectively cover an area of over 18,000 square kilometers. Management and operational plans will be developed and will define priority actions, cost coefficients for PA functions, human resource needs and infrastructural development, as well as rehabilitation and maintenance needs in all three parks. The project will support implementation of these plans, including (i) staffing the PAs; (ii) building, rehabilitating and maintaining infrastructure; (iii) procuring and maintaining equipment; and (iv) rendering, and outsourcing certain services (such as wildlife monitoring and research). The aim is to strengthen and ensure the internalisation of a number of PA functions that are either deficient or currently not being delivered under current management regimen. The project will support zonation within the parks and their boundary demarcation (including mapping and public consultation). This is particularly important in the parks where human settlement exists and activities incompatible with the conservation objectives of a category II PA are occurring. The bottom line is that some form of harmonization of the activities and expectations of the local populations currently living, legally or illegally, within Angola’s Protected Areas must be established. Management plans developed with the participation and consent of local communities, will also establish resource use thresholds in different zones (strict protection, tourism sustainable harvest of fuelwood; grazing and other uses), and systems for monitoring and enforcing resource use stipulations. Measures will be taken to address direct threats to biodiversity, including from poaching and uncontrolled wildfires—both by increasing the capacity of PA rangers to monitor threats and enforce management regulations, but also through community based natural resource management. Systems will be in place for monitoring the sites’ ecology, and the effectiveness of management measures. This will be done in partnership and collaboration with stakeholders currently active in the areas, e.g. Kissama Foundation in Quiçama, the Esso financed Giant Sable project in Cangandala and the Deutche Bank funded rehabilitation project in Bicuar. Multi stakeholder management boards and other applicable fora will be put in place as vehicles for consultation, decision-making and conflict resolution. Finally, the project will support an income generating initiative for target communities as a means to facilitate the collaboration of community members in the management of sites and to provide them with alternatives to activities that currently threaten biodiversity. Global benefits. The GEF funding will secure critically important biodiversity and deliver global benefits including the expansion of the PA network and the restoration and improved conservation of the habitat of endangered species such as Lowland Gorilla Gorilla gorilla, Western Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes, (plus 18 other primate species) and many endemic mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian and plant species. In particular, the lowland, escarpment and montane forest habitats that they occupy will be secured, bringing the total number of vegetation units within the PA network to 23 out of the 32 vegetation types recognised in Angola, and a total of 10 of the 15 WWF ecoregions found in Angola. The addition of the eleven new PA units (Table 4) will increase Angola’s PA system by a total of 9,050 sq km and more than double the current ecosystem representation in the PA estate. By project end, the total protected area estate will have expanded from 6.6% to 7.3% of the national territory, and PA coverage will better represent the globally significant and critical ecosystems in the country. Furthermore, the active rehabilitation of three national parks will ensure enhanced conservation security over 18,460 sq km. It will avert threats to biodiversity in several vegetation groups in the Zambezian centre of endemism, which is rich in fauna and flora within Angolan territory (see the specifics in Table 5). This includes, among others, the habitat in the region between the Cuango and Luando Rivers where the critically endangered sub-species Hippotragus niger variani still survives. B.3. DESCRIBE THE SOCIOECONOMIC BENEFITS TO BE DELIVERED BY THE PROJECT INCLUDING CONSIDERATION OF GENDER DIMENSIONS, AND HOW THESE WILL SUPPORT THE ACHIEVEMENT OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT BENEFITS (GEF TRUST FUND): In considering the socio-economic benefits of protected area rehabilitation and expansion, it is important to recognize the recent history of Angola. Protected areas were established under colonial rule, where access was restricted to the privileged elite, and local communities disenfranchised. This was followed by nearly three decades of civil war, where PAs were heavily exploited, primarily through the hunting of wildlife to meet protein needs. The displacement of millions of people into urban informal settlements further alienated a majority of Angolan people from the natural environment. Against this background, there is a need to change attitudes and value systems regarding biodiversity across the population at large. Nationally, there is however a growing awareness of national heritage – exemplified by the naming of the national football team the ‘Palanca pretas’ (Giant sable antelope), renaming the main coastal fishing city – Tombua – after Welwitschia mirabilis, and the use of Welwitschia as a popular brand name. Trivial as these advances might appear, they indicate a change from historical adverse perceptions of biodiversity amongst the populace to one of national awareness and pride – essential in any process of integrating biodiversity values and benefits into a war-ravaged country’s socioeconomic development. The project will make a major contribution towards further cultivating national pride in natural heritage. At the local level, PA development will mobilise significant investments in rehabilitation of infrastucture, training of PA personnel, basic Target 11 reads: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.” 10 National parks have been prioritised for rehabilitation in the ‘Strategic Plan for the Protected Area Network’. The three targeted parks were selected to benefit from this project because of the level of threat, the potential for the development of ecotourism and because of lack of other funding. 9 8 ecotourism facilities and guides, and opportunities for improved sustainable agricultural activities on the periphery of the PAs. It will pave the way for other investments, some of which can generate profit. Together with the sustainable livelihoods programme foreseen under Component 2, these activities are bound to generate some 2,000 direct jobs and many more indirect ones. The project will take specific measures to accommodate the subsistence and livelihood needs of PA resident and adjacent communities, permitting sustainable natural resource use opportunities in designated areas, and building the capacity of PA rangers and communities to collectively plan, monitor and enforce management measures to ensure sustainability. Gender equity has always been given high priority in Angola – and this is reflected in the environment sector, where the Minister is a fisheries biologist, and many of her senior management and technical team are female graduates. In developing the field staff for PAs, special attention will be given to gender balance and to ensuring that the benefits of PA development are equitably shared both in work opportunities and in provision of a supportive environment for working mothers. Similarly, the needs of women will be given special consideration in the PA management regimen to be developed, including with regard to gender representation in the PA Management Boards and natural resource management. B.4 INDICATE RISKS, INCLUDING CLIMATE CHANGE RISKS THAT MIGHT PREVENT THE PROJECT OBJECTIVES FROM BEING ACHIEVED: Risk Rating Management Strategy Capacities at different H A key activity under the project is to thoroughly assess the long-term needs for the development of PA management levels of government capacity (including capacity for improving the PA system’s financial sustainability). Linked to this, the project will and the finance facilitate the preparation of strategy for addressing these needs, as part of the overall strategy for sustaining the dedicated to PA enlarged PA system. The project is in fact a crucial step in addressing these capacity gaps through a long-term and management increase three-tiered approach (i.e. improving systemic, institutional and individual capacities). Yet, it is worth noting that the at a slower pace than UNDP/GEF projects (including this one and the GEF4 National Biodiversity Project) are not alone in addressing the required by the needs many identified PA management capacity gaps. More specifically, close collaboration with the AfDB’s ESSP project of a rehabilitated and will ensure that the formal tertiary and technical training of MINAB’s staff in areas such as biodiversity and natural expanded PA system. resource management (as well as other capacity building efforts) will effectively result in improved PA management capacity. This may e.g. involve the placement of capable individuals in PA management leadership positions, including in the field. Finally, high level political support will ensure that the PA agenda continues to grow in prominence and as a priority within the national development paradigm. Delays in staffing the M UNDP is currently engaged with the government of Angola in high-level discussions for the consolidation and new PA institution approval of its Environment Programme. The effective approval of the Law on Forests, Wildlife and Protected Areas and in approving key and the successful establishment and funding of INBAC are key topics in this dialogue. It is expected that by the end policy/legislation of the project development phase, these issues will already be satisfactorily addressed by government. If needed, may compromise the UNDP will invest own resources in targeted consultancies for facilitating the review of draft legislation, consultations achievement of and the adequate planning of INBAC’s institutional development. Other donor stakeholders (e.g. EU, African conservation targets. Development Bank, Spain and Norway) are equally involved in ensuring these barriers are overcome so that they will not represent a risk to PA and forestry related initiatives. This collective approach to management of this risk by interested parties will continue. Attitudinal rigidities H The involvement of communities living within and around PAs in the management of these areas is still incipient in amongst the local Angola. In fact, there is limited knowledge about how many settlements there are, their locations and size, and their populace viz. PAs impact on the protected landscape. In any case, a clear strategy for the active participation of communities in PA inhibit efforts to management, including PA benefit sharing, will be developed and implemented. This will guide the implementation change practices that of the sustainable natural resource use initiatives that will be implemented under component 2. These same degrade natural communities will be represented on PA management boards—giving them a voice as to how PAs are being managed. resources and Locally appropriate solutions to manage contra conservation land uses will be developed, with the full participation of threaten biodiversity communities. Land tenure conflict M Clear land use zonation and management arrangements are to be developed, ensuring that the rights of each may hamper the stakeholder are preserved, and defining their duties as well. The application of such protocols will be duly monitored. consolidation and With the exception of the Afro-montane forests, all of the proposed new PAs are in areas of low population density expansion of PAs. and low opportunity cost of land. For existing PAs, rehabilitation activities include zonation and conflict resolution mechanisms (to be implemented with the full involvement of local communities) as a means to address potential land conflict risks. Climate change will L This project will establish landscape scale buffer areas and where possible, corridors connecting PAs, which can act exacerbate habitat as a safeguard for PAs against the undesired effects of climate change by allowing biodiversity to alter distribution fragmentation in patterns in response to climate change effects. PA expansion is in and on itself a climate change adaptation strategy. terrestrial ecosystems. B.5. IDENTIFY KEY STAKEHOLDERS INVOLVED IN THE PROJECT INCLUDING THE PRIVATE SECTOR, CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS, LOCAL AND INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES, AND THEIR RESPECTIVE ROLES, AS APPLICABLE: The proposed project offers a unique opportunity to develop a stakeholder community around the PA theme – both within the framework of PA rehabilitation activities, and also in expanding the PA system. Key stakeholders at government level (ministries of environment, 9 agriculture, science and technology, education, etc.), within the extractive sector (Esso, BP, TOTAL and De Beers), and the nascent NGO sector (Juventude Ecologica Angolana, Associação para o Desenvolvimento Rural e Ambiente, and others) – will be actively drawn into the process of PA rehabilitation and expansion due to the inherent interest that can be stimulated by well managed and successful projects. While the government agencies, both national and provincial, must give policy and budgetary support and exert leadership, civil society must be engaged to ensure legitimacy and transparency of the entire biodiversity governance system. At the local level, the project will have to give special emphasis to developing participatory processes with the communities living within and adjacent to the PAs to ensure a fair and informed agreement about land use redefinition and where appropriate, zonation. While some of these people are relatively recent occupants of PA land (and some are technically illegal), many are traditional occupants of the land, and some (Khoisan, Himba, Mucubal) have rightful claims to use of these areas. All local population groups will be offered opportunities to participate in the development of the PA system, and to share in its benefits through work opportunities, social services and sustainable livelihoods resulting from the project. This will be ensured through the involvement of Angolan NGOs and CSOs, the strengthening of PA management boards and other consultative fora at PA level and the active involvement of the press in key project interventions. B.6. OUTLINE THE COORDINATION WITH OTHER RELATED INITIATIVES: The project and the PA agenda will be fully integrated into MINAMB’s programme of work and it is part and parcel of the new UNDP Overarching Programme in Support of the Environment Sector in Angola. Collaboration with other initiatives, programmes and projects will be ensured in order to mobilise not only co-financing to the project, but wider government support, including from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and its Institute for Forestry Development. Without these efforts, the attempts to clarify mandates for PA management would not be successful. It is important to stress that this PIF has been carefully designed to complement – and not overlap with – another important UNDP/GEF PA project (the National Biodiversity Project with focus on Iona National Park) and for which EU co-funding is being negotiated. Component 2 of the mentioned Iona project focuses on strengthening the institutional capacity to manage the PA network. Although related, there will be no overlap with respect to capacity building activities in both project. The development of both projects is being closely coordinated by MINAMB and UNDP to ensure that planned activities are complementary. Furthermore this project has a strong focus on capacity for dealing with the issue of PA finance, while the National Biodiversity Project focuses on general capacity for PA network planning, communication, monitoring and evaluation systems. In addition, this project will build on the lessons and successes from other UNDP/GEF projects (past and present), including: (1) the Enabling Activities project that supported the preparation of Angola’s NBSAP National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and Preparation of the First National Report to the Conference of the Parties; (2) the LD project Capacity Building for Sustainable Land Management in Angola; and (3) key International Waters initiatives in which Angola participates (in particular the Environmental Protection and Sustainable Management of the Okavango River Basin – EPSMO and Integrated Management of Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem – BCLME). Synergies and collaboration with a number of non-UNDP projects will be sought. In particular, collaboration and coordination with the AfDB ESSP project will be crucial for optimising capacity development results. The ESSP is contributing to the establishment, construction, equipping and staffing of the National Institute for Biodiversity and Conservation Areas and the Environmental Training School. Also, a GTZ pilot project for the integration of ex-combatants in PA rehabilitation is offering interesting solutions to the HR needs in PA surveillance works. Although the GTZ project is reaching its end in 2011 and the approval of a new phase is still unclear, such initiatives will be particularly useful in the implementation of the APAES that this project supports. At the level of pilot sites, synergies will be sought with different PA strengtheing projects, programmes and initiatives, inter alia: (i) the the Giant Sable survival programme in Candangala National Park (supported by corporate players); (ii) the several SADC sponsored TFCA initiatives, in particular in the south-east (Kavango-Zambezi “KASA” TFCA) and the north-west (Maiombe Forest TFCA) southwest (Iona-Skeleton TFCA); (iii) PA strengthening initiatives in Quicama’s fenced area (with Kissama Foundation), in Cangandala (supported by Esso and others) and in Bicuar (funded by Deutsche Bank via a Spanish firm). C. DESCRIBE THE GEF AGENCY’S COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE TO IMPLEMENT THIS PROJECT: ‘Protected Areas’ are one of UNDP’s signature programmes and the agency has a large portfolio of PA projects across Africa dealing with PA institutional and management strengthening, as well as PA network expansion. These projects implement strategies attuned to the African reality. The UNDP Country Office in Angola, supported by the UNDP Regional office in South Africa, will oversee and provide support to this project, relying on UNDP's country-level coordination experience in integrated policy development, human resources development, institutional strengthening, and non-governmental and community participation. C.1 INDICATE THE CO-FINANCING AMOUNT THE GEF AGENCY IS BRINGING TO THE PROJECT: UNDP will provide $2,000,000 in direct co-financing to this project in the form of a grant. The source is UNDP’s core funds (TRAC). In addition, UNDP and the government will help leverage the rest of the co-financing necessary for meeting the targets proposed under this PIF. MINAMB is currently negotiating a public investment programme for PAs and INBAC. It is worth noting the UNDP has been supporting capacity building for biodiversity management in Angola for the past 14 years, since the inception of a support programme co-funded by Norway and UNDP. These previous interventions have in many respects prepared the ground for the set of PA related 10 activities proposed under this project. UNDP has demonstrated its comparative advantage to be the GEF agency for this project based on its large global portfolio, extensive experience in this PA management, in developing the capacity at the system’s level (policy, governance, institutions and management know-how) to allow for the strategic expansion and strengthening of Angola’s PA system. The present project, as well as the recently inherited PA project with focus on Iona NP, will benefit from, as well as contribute to, UNDP’s past and current work in Angola, particularly in relation to sustainable environmental management. C.2 HOW DOES THE PROJECT FIT INTO THE GEF AGENCY’S PROGRAM (REFLECTED IN DOCUMENTS SUCH AS UNDAF, CAS, ETC.) AND STAFF CAPACITY IN THE COUNTRY TO FOLLOW UP PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION: UNDP Angola is in the final stages of development and approval with the government of an overarching programme in support to the environment sector in Angola. Its goal is to “strengthen national capacities to mainstream environmental protection into national development plans and programmes within a pro-poor growth perspective”. The programme will congregate a number of related initiatives financed by government, donor agencies (including the EU and the AfDB) and private sector. It will also provide the sectorwide framework for the PA agenda to flourish. More specifically, this project contributes to Outcome 2 of the mentioned UNDP Environment Programme (Effective implementation of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan and the National Environment Management Plan). The UNDP Country Office counts on at least three professional staff dedicated to the environment portfolio (plus support from operations and senior management). This team is supported by UNDP/GEF Regional Coordination Unit (including a Portuguese speaking Regional Technical Advisor and support staff assisting with M&E and delivery oversight, among other tasks). Two key strategy documents provide a chapeau for the project’s fit within the UN’s and UNDP’s Programmes in Angola: respectively the United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UDAF) and the Country Programme Action Plan (CPAP). As for the first, this project will make a key contribution to UNDAF’s Support Area 4 (Sustainable Economic Development), under which a concerted UN approach is geared to provide a framework for national and decentralized institutions strengthened integrated rural development, ensuring food security with due consideration for environmental protection, natural resource management and adaptation to climate change. With respect to the CPAP, recommendations from the 2009 CPAP Annual Review indicated that UNDP should focus on building strategic ties and defining priorities for its engagement in environmental protection at the central level with the Ministry of Environment. As a result, the Environment Programme (2011-2013) was prepared through a consultative process and will be launched in 2011. The Environment Programme will contribute in particular to CPAP’s pillar #4 on Environment and Sustainable Development. PART III: APPROVAL/ENDORSEMENT BY GEF OPERATIONAL FOCAL POINT(S) AND GEF AGENCY(IES) A. RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT OF GEF OPERATIONAL FOCAL POINT (S) ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT(S): (Please attach the Operational Focal Point endorsement letter(s) with this template. For SGP, use this OFP endorsement letter). NAME Mr. Pedro Samuel POSITION CEO for the National Environment Fund and GEF Operational Focal Point MINISTRY Ministry of Environment DATE (Month, day, year) Apr 28 2011 B. GEF AGENCY(IES) CERTIFICATION This request has been prepared in accordance with GEF/LDCF/SCCF policies and procedures and meets the GEF/LDCF/SCCF criteria for project identification and preparation. Agency Coordinator, Agency name Yannick Glemarec, UNDP/GEF Executive Coordinator Date Signature (Month, day, year) August 30, 2011 Project Contact Person Fabiana Issler, Regional Technical Advisor for Biodiversity, Africa, UNDP / Environment Finance Group Telephone Email Address +27-123548182 fabiana.issler@undp.org 11 Annex Tables to the PIF Table 2. Major biomes/vegetation groupings and mapped vegetation units (Barbosa 1970) in Angola Biome/vegetation grouping Barbosa units Area, km2 Moist forests 1,2,3,4 27 879 Forest/savanna mosaic 7 – 11; 13, 14; 22; 26 295 930 Afro-montane forest 5,6 170 Miombo woodlands and savannas 15 – 19; 24,25 671 806 Mopane woodlands and shrublands 20,21 78 109 Acacia/Adansonia savannas and thickets 23, 27 57 521 Edaphic grasslands 12, 30 - 31 110 945 Desert 28, 29 14 340 Percentage 2,2 23,5 0.01 53,5 6,2 4,6 8,8 1,1 Table 3. Vegetation types of Angola (from Barbosa 1970; Huntley 1974) with the area of each falling within the protected areas listed in Table 2. In addition, the 11 new protected areas proposed in this report, indicated in italics, will increase the coverage of Angola’s 32 vegetation types from the current 11 to a total of 23, thereby more than doubling the representation of Angola’s biodiversity in the Protected Area system, while only increasing the area under conservation management by less that 10%. Vegetation type Formation, moisture regime 1. Forest, humid, evergreen, 2. Forest, semi-deciduous 3. Typical genera Total area, km2 481 Protected area, km2 current/ New 200 % of total area currently protected 0 Protected area Existing/ proposed 3,765 200 0 Maiombe Forest, humid, semi-deciduous Gilbertio dendron, Tetraberlinia Gossweilerio dendron, Oxystigma Celtis, Albizia 20,989 350 0 4. 5. Forest, dry, semi-deciduous Forest, humid, semi-deciduous Cryptosepalum Newtonia, Parinari 2,163 160 0 50 0 0 6. Forest, humid, semi-deciduous Podocarpus 10 150 0 7. Forest/savanna mosaic, humid Piptadeniastrum, Bosqueia 13,699 0 0 Serra Pingano, Gabela, Serra Kumbira Serra da Neve, Serra da Chela Morro Moco, Morro Namba, - 8. 9. 10. Forest/savanna mosaic, humid Forest/savanna mosaic, humid Forest/savanna mosaic, mesic 79,631 27,798 11,465 300 0 0 0 0 0 Lagoa Carumbo 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Forest/savanna mosaic, mesic Thicket/savanna mosaic, humid Thicket/savanna mosaic, humid Thicket/savanna mosaic, mesic Woodland /thicket mosaic, mesic Woodland, humid Marquesia, Berlinia Celtis, Hyparrhenia Allanblackia, Entandraphragma Pteleopsis, Adansonia Landolphia, Hyparrhenia Annona, Piliostigma Crossopteryx, Heteropogon Baikiaea, Ricinodendron 14,900 46,705 27,798 12,497 16,422 745 900 0 0 9,497 5 0 0 0 72 Quicama Lagoa Carumbo Bicuar, Mupa Julbernardia, Brachystegia 138,754 150 0 Brachystegia,Marquesia Brachystegia, Julbernardia Brachystegia Colophospermum Colophospermum, Acacia Cochlospermum, Combretum Adansonia, Sterculia Brachystegia, Burkea 224,393 74,333 5,367 69,777 8,332 27,718 21,951 114,560 1,882 7,693 0 3,551 0 100 9,028 0 3 26 0 5 0 0 41 0 25. 26. 27. Woodland, humid Woodland, humid Woodland, mesic Woodland, mesic Woodland, mesic Savanna/woodland, humid Thicket/savanna mosaic, arid Woodland, savanna mosaic, mesic Savanna-woodland, mesic Savanna-woodland, mesic Savann-grassland mosaic, arid Morro Moco Morro Namba Luando, Cameia L, B, Cangandala Iona, Mupa Serra Kumbira Quicama - Baikiaea, Guibourtia Adansonia, Peucedanum Acacia, Commiphora 142 580 108,231 35,570 3000 400 9,056 7 0 27 28. Grassland, shrubland, sub-desert Aritida, Welwitschia 9,934 7,311 74 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. Maiombe - Luiana Serra Mbango Iona, Namibe, Chimalavera Iona, Namibe 12 Vegetation type 29. 30. 31. 32 Formation, moisture regime Desert Swamp Grassland, floodplain Grassland, montane Typical genera Total area, km2 Odyssea, Acanthosicyos Cyperus, Typha Loudetia Protea, Stoebe 4,406, 1,362 49,990 12,898 Protected area, km2 current/ New 4,406 186 14,024 100 % of total area currently protected 100 14 31 0 Protected area Existing/ proposed Iona Quicama Cameia Morro Moco, Morro Namba Table 4. Priority areas for gazettal according to the Angolan Protected Area Expansion Strategy (APAES) Name of the proposed new PA Maiombe Serra Pingano Lagoa Carumbo Serra Mbango Floresta da Gabela Serra Njelo, Floresta de Kumbira Morro Namba Morro Moco Serra da Neve Mussuma Serra da Chela Indicative hectarage of proposed priority areas for expansion according to the APAES (ha)* 40,000 35,000 200,000 40,000 15,000 15,000 10,000 10,000 20,000 500,000 20,000 Note Província de Cabinda, 4.40 S; 12.32 E; altitude 350 m Província do Uige, 7.41 S; 14.53 E; alt. 750 m Província da Lunda Norte, 7.48 S; 19.56 E; alt. 850 m Província de Malange, 8.44 S; 17.06 E; alt. 1100 m Província do Cuanza Sul, 10.42 S; 14.18 E Província do Cuanza Sul, 11.00 S; 14.17 E Província do Cuanza Sul, 11.52 S; 14.44 E; alt.2420 m Província do Huambo, 12.25 S; 15.11 E; alt. 2620m Província de Namibe, 13.42 S; 13.09 E; alt. 2489 m Província de Moxico, 14,00 S; 21,45 E; alt.1050 m Província da Huila Province, 15.00 S; 13.16 E; alt. 2327 m Total indicative hectarage 905,000 * The precise hectarage of proposed sites is still under discussion, to the extent that the ‘Strategic Plan for the Protected Area Network’ is still undergoing technical scrutiny and wider consultations. At CEO Endorsement stage, more precise figures for the PA expansion to be financed both by the GEF and the project’s associated co-financing will be presented. Table 5. Key features and threats of the national parks targeted for rehabilitation under this project. Bicuar 7,900 sq km Quiçama 9,600 sq km Cangandala 630 sq km Established as a hunting reserve in 1938. National park since 1964. Located in Huíla Province and surrounded by several agro-pastoral small settlements. The vegetation is typically woody and bush savannah with extensive woodland-thicket mosaics. The park harbours large populations of buffalo (Syncerus caffer caffer), leopards, gnus, kudus and various species of buck in large numbers. Hunting pressure, lack of management and sub-effective anti-poaching measures are threatening faunal populations. Uncontrolled fire is a main hazard during the dry season. Established as a hunting reserve in 1938. National park since 1957. Located in Northern Angola, 75 km south from Luanda, between the Atlantic Ocean, the Cuanza river and the Longa river. The park straddles significant variations in vegetation, from the banks of the Cuanza river in the north into the park with mangroves, dense forest, forest-savannah mosaics, woodland and dry tropical forest with cacti and baobab trees. The park still harbours rich and varied fauna, including the threatened African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), roan (Hippotragus of equinus), the typically Angolan primate talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin), marine turtles (all threatened) and varied avifauna. Currently only a small fraction of the park is being managed, in spite of the park's potential for ecotourism. Some areas are dedicated to activities and settlements not normally associated with a national park. A national road cuts through the park in its north-south axe. Established as an integral nature reserve in 1963. National Park since 1970. Located in Malanje Province in the confluence of several important rivers. The park was initially established to protect the Giant Sable Antelope (Hippotragus niger variani), which is critically endangered. Currently, the park contains a sanctuary, or a fenced area, where a captive breeding programme for the Giant Sable is being carried out with the only surviving population of this sub-species. The park harbours otherwise varied flora and fauna. A mosaic of open miombo bushveld and savannah occur. Brachystegia-bushveld are found on the water partitions and open grasslands in the lower-lying drainage lanes. The potential for eco-tourism is considerable. Threats to biodiversity include uncontrolled hunting and burning by the resident population—likely some 5,000 inhabitants by now. 13