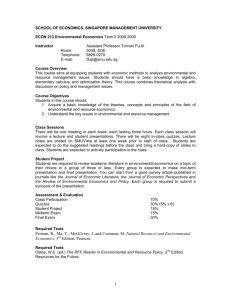

Economics of the Environment and Natural Resources

advertisement

Economics of the Environment and Natural Resources Tutor • Roger Perman (Economics) Overview • • • This module does not assume a prior background in economics. It does assume familiarity with the nature and origins of the problem of sustainable development. The concepts and tools of economic analysis are explained and applied to sustainable development issues such as environmental pollution, natural resource exploitation and nature conservation. Objectives Successful participants will: • • • understand the strengths and weaknesses of the economic approach to environmental management; know how to economically appraise projects with environmental impacts; understand economic arguments about the merits of alternative instruments for environmental protection, such as taxes and tradable permits. Economics of the Environment and Natural Resources Assessment • Students are assessed on the basis of a project report and one essay, the latter being chosen from a set of titles distributed in advance and then being completed under examination conditions. The weighting of each element is equal, and so the report and the exam each contribute 50% towards the final mark. Reading List • • • The core text is: Common, M. S. 1996. Environmental and resource economics: an introduction. 2nd edition. Longman, which assumes no previous knowledge of economics, and uses no mathematics beyond elementary algebra. Students who have previously studied economics and who have a reasonable mathematical background (particularly some calculus), may find Perman, R., Ma, Y., McGilvray, J. and Common, M. 2003. Natural resource and environmental economics. (Third Edition. Longman, Harlow) more suitable. Readings on particular topics will be provided as the module proceeds. Web page with access to class materials • http://www.economics.strath.ac.uk/rp/GSES_Class_Notes.htm Syllabus 1. • Basic micro and welfare economics. This deals with what markets do under ideal conditions, the concept of efficiency, and with departures from ideal conditions and their consequences. (Chapters 2, 3 and 4 in Common, or Chapters 1, 5 and 11 in Perman et al.) 2. The economics of environmental pollution. • This deals with pollution seen as resulting from market failure, with how economists think standards for pollution control should be determined, and with the economic analysis of alternative ways of controlling pollution. (Chapter 5 in Common, and Chapters 6-10 and 16 in Perman et al.) 3. Discounting and project appraisal. • The concept of efficiency is extended to include the time dimension, and forms the basis for the appraisal of investment projects using discounted present values. (Chapters 6 and 8 in Common, and Chapter 11 in Perman et al.) 4. Cost benefit analysis and the environment. • Cost benefit analysis is project appraisal conducted from a social and economic, rather than a financial, perspective. Here the use of cost benefit analysis to consider projects which damage, or are intended to protect, the natural environment is dealt with. This involves looking at techniques for valuing the environment. (Chapter 8 in Common, and Chapters 11, 12 and 13 in Perman et al.) 5. Natural resource exploitation. • This deals with the way economists consider the use of non-renewable resources (minerals) and of renewable resources (forests, fish stocks), by using the extended concept of efficiency. (Chapter 7 in Common, and Chapters 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 in Perman et al.) 1. Basic micro and welfare economics. • Introduction to some relevant economics concepts • Deals with what markets do under ideal conditions, the concept of efficiency, and with departures from ideal conditions and their consequences. • Reading: Chapters 2, 3 and 4 in Common, or Chapters 1, 5 and 11 in Perman et al. The “ideal conditions” To be defined and examined later: 1. the absence of external effects; 2. the absence of public goods or bads; 3. all households and firms have complete information; 4. all households and firms act as price takers. The key result • If the full set of "ideal" conditions listed above is satisfied, then • Markets would bring about efficient allocations of resources. • Meanings: • The net benefit that society as a whole can obtain from a given set of scarce resources is maximised • The mix of goods and services being produced, and the relative quantities being produced of each, are ones that maximise social well-being (for any given distribution of income and wealth) • Resources are not being wasted (no different pattern of use of resources is available such that one can be made better off without at least one other person being made worse off) Why might a competitive market economy “automatically” generate efficient outcomes? Essential ideas: take a single good or service, X • • • • • Net Benefit = Total (Gross) Benefit – Total Cost NB = B – C NB(X) = B(X) – C(X) Note that B and C depend ONLY on X (i.e. No externalities) We are now going to show that a competitive market in X will bring about maximisation of NB. • It does so through the forces of market supply and market demand What might we expect the NB function to look like? • NB(X) = B(X) – C(X) • Remember, at this point we assume that B and C depend ONLY on X (i.e. No externalities) • Seems likely that B(X) will rise as X rises; but at a decreasing rate • Seems likely that C(X) will also rise as X rises; but at an increasing rate B(X) and C(X): Likely shapes 3500 3000 B C 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 NB(X) Evidently NB is maximised when X is approximately 50 NB=B-C 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70 A little maths • NB(X) = B(X) – C(X) • One condition for NB to be at a maximum is that its first derivative with respect to X is zero. That is, dNB/dX = NBX = 0 This implies NBX = BX – CX = 0 and hence • BX = CX or Marginal Benefit of X = Marginal Cost of X MB and MC 70 MB 60 MC 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 It turns out that in a competitive market economy, MB(X) is equivalent to the market demand curve for X Price of X D(X) = MB(X) Quantity demanded per period of X It turns out that in a competitive market economy, MC(X) is equivalent to the market supply curve for X Price of X S(X) = MC(X) Quantity supplied per period of X Price S P* D X* Quantity per period of X S = MC Price P* D = MB Q* Quantity per period One person’s willingness-to-pay, WTP (i.e. demand) for X Price 43 35 D = MB = Marginal willingness to pay 1 2 Quantity of X per period Price Adding up individual demands to get market demand D1 X1 X2 D2 X = X1 + X2 D1+D2 =D = Social MB Quantity per period P £60 Consumers’ Surplus £35 D Consumers’ Expenditure 0 20 The value consumers obtain X P 0 25 30 Consumers obtain more value if they have more of the good X P Original consumer surplus Increased consumer surplus 0 25 30 Consumers obtain more value if they have more of the good X One firm only Price Si = MC 10 7 4 1 2 3 Quantity per period Adding up individual firm’s supplies to get market supply Price S1 S2 Market Supply (=S1+S2) P X1 X2 X = X1 + X2 Quantity per period P S Producers’ Surplus £5 Producers’ Total Variable Costs 0 20 The value obtained by producers X P S 0 30 X Producers may be able to obtain more value if they sell more goods Maximised sum of consumers and producers surpluses at the market equilibrium price and quantity traded S P Consumer Surplus P* Producer Surplus D X* X WE HAVE SEEN THAT: • Markets may bring about efficient allocations of resources. • But EFFICIENT outcomes require that a set of "ideal" conditions are satisfied. • the absence of external effects; • the absence of public goods/bads; • all households and firms have complete information; • all households and firms act as price takers. • Next time we shall investigate what outcomes are when these conditions are not all satisfied. Particular focus will be given to environmental goods and services.