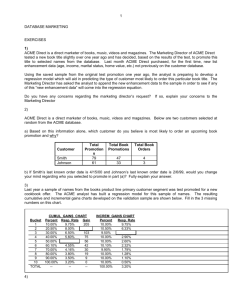

Fall 2012 (all except Question 1)

advertisement

1 Accounting for Lawyers Professor Bradford Fall 2012 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. In some cases, the result is unclear; the position taken by the answer outline is not necessarily the only justifiable conclusion. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on your printed exam. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question Question Question Question Question Question Question 1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: 7: Range Range Range Range Range Range Range 3-9; 5-9; 0-9; 0-9; 2-9; 2-9; 0-9; Average Average Average Average Average Average Average = = = = = = = 6.00 7.04 6.26 3.78 5.61 7.74 6.57 Total Exam Score (70% of grade): Range 4.68-8.18; Average = 6.05 Homework (30% of grade): Range 8-9; Average = 8.48 All of these grades are on the usual law school scale, with 9 being an A+ and 0 being an F. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. 2 Question 1 The answers to Question 1 are contained in a separate Excel file. 3 Question 2 One important aspect of the auditing process is independence. Auditors are supposed to provide an independent check on the accuracy of the financial statements prepared by a company ’s management. If the auditor is “captured” by management, that independent check is lacking. Auditing firms are already required to rotate the lead and reviewing partners assigned to a particular company at least every five years. But the firm itself may continue to audit the company year after year; the company is not required to change auditing firms. If companies are required to rotate their audit firms every few years, the auditors are less likely to become “cozy” with the audited company’s management and therefore will press them harder on questionable transactions and procedures. Audit firm rotation also reduces the financial incentives to go along with management; the potential loss of revenue is less if the auditor is going to lose the client in less than five years anyway. In addition, if an auditor knows someone else will be reviewing its work when the change occurs, it is more likely to exercise care and take an aggressive stance against management positions. However, a rotation requirement like this would undoubtedly increase the expense of auditing. Each time a chan ge was made, the new auditor would have to familiarize itself with the client company ’s business and accounting systems. The cumulative expertise and knowledge that is gained by auditing a company over a long period of time would be lost. In addition, firm rotation could possibly affect independence in the opposite direction than intended. Currently, the expectation is that a company will continue to use the same auditing firm. If the company hires a new auditor, that is extraordinary and may signal a probl em. This makes it difficult for an audited company to change auditors if the existing firm is too aggressive in challenging management practices. 4 Under the proposed system, auditor change would be regular and expected. A company could more easily get rid of an aggressive auditor and find a less aggressive firm. Further, to get new business when changes are made, auditors might have an incentive to develop a reputation for going along with management, because management might be more inclined to choose an audit firm with a lax reputation when the time for change arises. 5 Question 3 A. The depreciable cost of a long-lived asset is its purchase price plus the cost to bring it to the location and condition of its intended use. In this case, the depreciable cost would be the purchase price of $100,000, plus the shipping cost of $5,000, plus the installation cost of $3,000, for a total of $108,000. The double-declining-balance method applies the applicable rate to the full cost, without subtracting its salvage value. The depreciation rate is twice the normal straight-line rate. Since the machine has a useful life to Acme of eight years, the normal straight -line rate would be 12.5% (1/8). Thus, the double-declining-balance rate is 25%. Year 2012 2013 Depreciable Depreciation Depreciation Book Value Cost Rate Expense $108,000 .25 $27,000 $81,000 $81,000 .25 $20,250 $60,750 Depreciation Expense 2012 = $27,000 2013 = $20,250 B. The balance sheet listing for machinery would look like this: Machinery Less: Accumulated Depreciation Machinery (Net) $108,000 47,250 $ 60,750 6 Question 4 It is, of course, impossible to know, simply by looking at these financial statements, if the numbers presented are accurate. For all we know, Acme simply made up these numbers. These financial statements are unaudited, so an auditor has not even reviewed Acme ’s accounting to see if Acme has sufficient internal controls or if Acme has complied with generally accepted accounting principles. Having said that, however, even assuming these figures are accurate, a couple of things cast doubt on the extent of Acme ’s “improvement.” First, in the past year, the value of Acme’s inventory has dropped dramatically. Acme uses the LIFO (last-in, first-out) method of valuing inventory. The last inventory items Acme made or purchased are assumed to be the first sold, so the remaining inventory that appears on the balance sheet consists of the oldest items. If, as is usually the case, the cost of inventory to Acme is rising, the value on the balance sheet is less than the current replacement cost to Acme. The reduction of inventory from 2011 to 2012 means that Acme has sold some of its existing inventory without totally replacing it. The Cost of Goods Sold, an expense that reduces net incom e, is thus lower because it’s based on the older inventory costs of that existing inventory, not current costs. Acme’s net income for 2012 is higher in part simply because the expenses are lower due to the inventory sell off. Second, Acme’s accounts receivable increased significantly from 2012 to 2012, indicating that many of Acme’s sales were credit sales. Acme may be boosting its income by selling to people who don’t currently have the cash to pay. If so, Acme may at some point have to charge off those accounts and take a loss. Note that Acme took no bad debt expense in 2012 to reflect the possible uncollectibility of those accounts, even though its accounts receivable increased by over $1 million. Even if most of those accounts are collectible, certainly some of them will not be. Acme is estimating that only 2.9% ($40,000 of $1,365,000) of all its accounts receivable will not be collected. Given 7 that most of these accounts are new, that’s certainly within the realm of reason, but the corresponding percentage in 2011 was 14%. 8 Question 5 A. Earnings per share = Net Income/Number of Shares = $1,132,000/200,000 = $5.66/share B. Interest Coverage Ratio =Earnings Before Interest and Taxes (EBIT)/Interest Expense [EBIT = Net Income (After Taxes) + Income Taxes + Interest Expense = $1,132,000 + 126,000 + 79,000 = $1,337,000] Interest Coverage Ratio = $1,337,000/$79,000 = 16.924 C. Return on Equity = Net Income/Equity, Prior Year = $1,132,000/$1,349,000 = .839 (83.9%) 9 D. Inventory Turnover Ratio = Cost of Goods Sold/Average Inventory = $690,000/(($214,000 + $879,000)/2) = $690,000/$546,500 =1.26 E. Cash Return on Assets = Net Increase (Decrease) in Cash/Total Assets, Prior Period = $697,000 - $250,000/$2,239,000 = .1996 (19.96%) 10 Question 6 The lead partner is wrong. Because money has time value, it matters when Omega pays the various sums, even if in both cases the total payment is $500,000. In general, the later the payment the better, because Omega can earn a return on the funds it holds prior to payment. The easiest way to compare the two options is to determ ine the present value of each. The one with the lowest present value is the better option for Omega. Option 1 The present value of $170,000 paid now is simply $170,000. We can determine the present value of the ten annual payments using the annuity table on p. 254 of the textbook. The number of years is 10 and the discount rate is 5%. The present value factor from the table is therefore 7.722. Thus, the present value of these payments is $33,000 x 7.722 = $254,826. The total present value of Option 1 is the refore $170,000 + $254,826 = $424,826. Option 2 The present value of this option can be determined by separating it into two components, an annual payment of $75,000 for five years and a lump-sum payment of $125,000 at the end of six years. The first component is an annuity that we can value using the table on p. 254 of the textbook. The number of years is 5 and the discount rate is 5%, so the present value factor is 4.329. Thus, the present value of this annuity is $75,000 x 4.329 = $324,675. We can determine the present value of the lump-sum payment using the table on p. 252 of the textbook. The period is 6 years and the 11 discount rate is 5%, so the present value factor is .7462. Thus, the present value of this payment is $125,000 x .7462 = $93,275. [Alternatively, we could determine this using the present value formula: PV = $x/(1 + r) n , where x = the amount to be paid; r = the discount rate; and n = number of periods. PV = $125,000/(1+ .05) 6 = $125,000/1.34010 = $93,276.62] The total present value of Option 2 is therefore $324,675 + $93,275 = $417,950. Result Option 2 is the preferable settlement. Its cost to Omega is $6,876 less in present value terms. 12 Question 7 This is a contingent gain that Alpha may or may not realize. Under the FASB standards, gain contingencies are never accrued and recognized in the financial statements. Alpha should not recognize the gain until after it wins the case, not matter how certain it is of victory. Since the contingency is material, Alpha should, however, disclose the contingency in the notes to its financial statements. The standard for disclosing contingent gains is unclear, but presumably it mirrors the standard for losses, which should be disclosed if they are at least “reasonably possible.” A contingency is at least reasonably possible if its likelihood is more than remote. “Remote” means the chance of it occurring is slight. If, as the attorney indicates, this gain is “almost certain,” its likelihood is clearly more than slight, and i t should be disclosed. However, Alpha should be careful not to mislead people as to the likelihood of a win.