View/Open - ScholarsArchive@OSU is Oregon State University's

advertisement

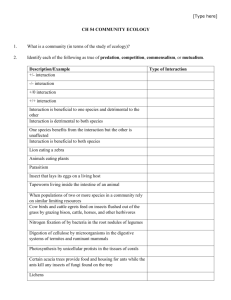

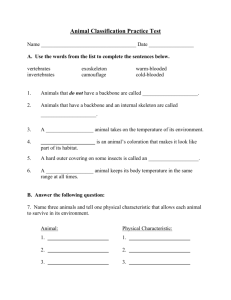

Variation in Leg Color Does Not Influence Courtship Success in the Red-legged Salamander, Plethodon shermani Christy Baggett, Sarah Eddy, and Lynne Houck Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 Abstract The ritualized courtship of the Red-legged salamander, Plethodon shermani, has been studied extensively. Males and females possess brightly colored red legs, but little is known about the implications of this coloration on mate choice. An alternative hypothesis is that coloration may be used as a warning signal to predators. Animals were collected in North Carolina and scored for leg coloration (1-10). To test the hypothesis of mate choice, male and female animals varying in leg coloration were paired together in courtship trials and observed every 2 minutes. Linear regressions were performed on data collected to test the predictions that (1) leg color is sexually dimorphic, (2) females prefer males with red legs, and (3) red coloration is condition-dependent. These analyses determined that none of the predictions were sufficient support for the hypothesis of sexual selection for leg coloration; this lack of support gives strength to the alternative hypothesis of aposematic coloration by way of natural selection. Discussion Introduction • In Plethodon shermani a visual display performed by the male, foot-dancing, increases the likelihood of mating success (Eddy 2012). • Another visual cue in P. shermani, red leg coloration, and the role it may play in either natural or sexual selection is not understood. • Research Question: Why do P. shermani have red legs? • In three-spined sticklebacks, females prefer males based on the intensity of red on their bodies (Milinksi & Bakker 1990), an example of coloration due to mate choice. • If sexual selection is responsible for red leg coloration, then we might expect: 1. Leg color to be sexually dimorphic 2. Female preference for males with red legs 3. Red coloration to be condition-dependent Figure 4. (A) Each male was placed in box with one female. Trials conducted under low light conditions to mimic levels in the field. (B) 40 pairs observed each trial. Trials ran for 10 nights, with 1-2 days before the next observation. A B Figure 5. Variation in leg color of P. shermani ranges from very dark to bright red. Results Figure 1. Amount of red coloration on legs does not vary based on sex (β = 0.1311 ± 0.1716, p = 0.445). Figure 2. Males with red on their legs were no more successful in courtship than males with darker legs (β = -0.003963 ± 0.005563, p = 0.481). Figure 6. Female three-spined stickelbacks prefer mates with more intense color because it reveals physical condition (Milinski & Bakker 1990). Methods • Animals collected from Macon Co., N.C. in August 2011. • Biometric data collected (weight, snout-vent length, etc). • Front and back legs assigned color score. 1 = < 10% red 4 = 70-89% red 2 = 11-39% red 5 = full sleeve, > 90% red 3 = 40-69% red Total = front + back • Courtship trials: each male paired with female and behavior of male was recorded every 2 minutes. • Results do not support the sexual selection hypothesis of red legs as consequence of mate choice. 1. Red leg coloration is not sexually dimorphic (Figure 1). 2. Females did not preferentially mate with males who had red legs (Figure 2). 3. Variation in red coloration did not correlate with differences in body condition (Figure 3). • Insufficient evidence for mate choice strengthens the alternative hypothesis of aposematic coloration, a result of natural selection. • Taricha granulosa are a great example. Animals of this species exhibit orange coloration on their ventrum as an aposematic (warning) signal to advertise their extreme toxicity (Brodie et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 1975). Figure 3. Body condition (weight/snout-vent length) was no greater for males with red leg coloration than for those with dark legs (β = -8.279 ± 11.538, p = 0.47745 ). Figure 7. The orange color on the ventral side of Taricha granulosa is an example of aposematic coloration warning predators of the newt’s lethal toxin (Brodie et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 1975). References • Brodie, E. D., III, C. R. Feldman, C. T. Hanifin, J. E. Motychak, D. G. Mulcahy, B. L. Williams, and E. D. Brodie, Jr. 2005. Parallel arms races between garter snakes and newts involving tetrodotoxin as the phenotypic interface of coevolution. J. Chem. Ecol. 31:343–356 • Eddy, S. L. 2012. Mutual Mate Choice in a Terrestrial Salamander, Plethodon shermani, with Long-Term Sperm Storage (Doctoral dissertation). Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. • Johnson, Judith A., and Edmund D. Brodie, Jr. 1975. The selective advantage of the defensive posture of the newt Taricha granulosa. Am. Midl. Nat. 93:139–148. • Milinski M, Bakker TCM, 1990. Female sticklebacks use male coloration in mate choice and hence avoid parasitized males. Nature 344:330-333.