Lecture 12

advertisement

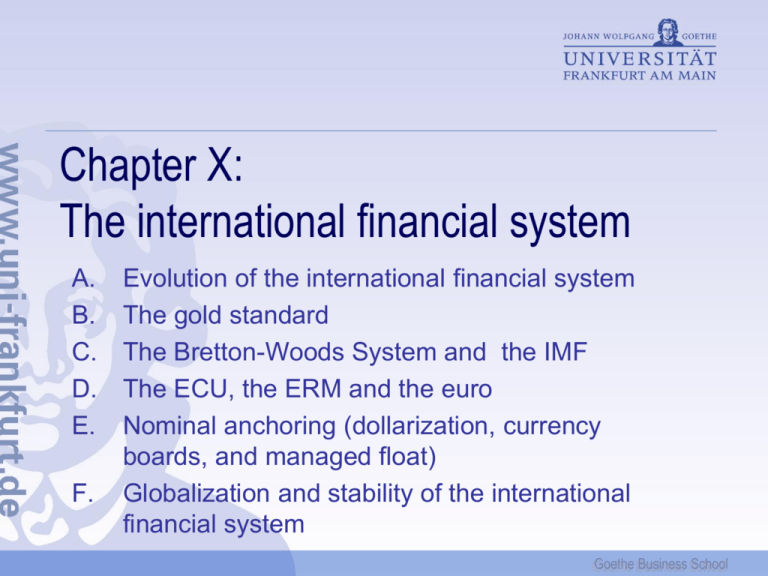

Chapter X: The international financial system A. B. C. D. E. F. Evolution of the international financial system The gold standard The Bretton-Woods System and the IMF The ECU, the ERM and the euro Nominal anchoring (dollarization, currency boards, and managed float) Globalization and stability of the international financial system Goethe Business School Evolution of the international financial system Before World War I, the world economy operated under the gold standard It means that most world currencies were backed by, and convertible into gold. For currencies whose unit is permanently tied to a certain quantity of gold, the gold standard represents a fixed-exchange rate regime To see how it works we take an example: 2 Goethe Business School Operation of the gold standard (1) The exchange rate between the $ and the £ is effectively fixed at $5:£1 via the common denominator gold As the £ appreciates beyond $5 in financial markets, an American importer importing goods for £100 from the UK would have to pay more than $500 This importer could arbitrage against the “financial” £ by exchanging $500 for gold, shipping it to the UK, and converting it into £100 at the fixed gold parity 3 Goethe Business School Operation of the gold standard (2) An appreciation of the £ leads to British gains in international reserves, and an equal loss in international reserves in the United States It entails a commensurate expansion of base money in Great Britain, and a contraction of base money in the United States This must raise the British price level, and provoke a deflation in the US It causes a depreciation of the £ against the $ until the former parity is reinstalled 4 Goethe Business School “Price-species-flow” mechanism Price adjustments under fixed exchange rates work through symmetries in the supply of base money between two countries One country loses international reserves, the other gains international reserves This mechanism will ultimately entail a countervailing adjustment of price levels for goods and services in each country This “price-species-flow” mechanism was first described by David Hume 5 Goethe Business School Example: The U.S. during the 1870s During the Civil War in the US, the gold standard had been abandoned and the government had issued significant amounts of paper money to finance the war In the end, this had lead to an almost doubling of the price level After the war, the US returned to the gold standard at the parity that had reigned before. This (“shock”) contraction of the money supply caused the depression of 1873-79 6 Goethe Business School Return to the gold standard after WW I After World War I most countries tried to return to the gold standard International trade was mainly carried out in British pounds, French francs, US dollars, all (partially) covered by gold Payments were made in gold certificates (promissory notes denominated in gold), the volume of which increased by credit expansion The Great Depression caused insolvencies in gold, which brought the gold standard to an end 7 Goethe Business School The Bretton-Woods System In 1944, the post-war international economic order was conceived in the little town of Bretton Woods (New Hampshire) The three international institutions created are the International Monetary Fund (IMF); the Bank for Reconstruction and Development (Worldbank); the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now World Trade Organization (WTO) 8 Goethe Business School The Bretton-Woods System The international financial system (Bretton-Woods System) was based on gold and the US dollar The parity between the dollar and gold was fixed at $35 for an ounce of gold The exchange rates of other countries adhering to the system were pegged to the dollar Discretionary exchange-rate adjustments were possible in the case of “fundamental balanceof-payments disequilibria” 9 Goethe Business School Forex interventions by central banks If the domestic currency was undervalued, the central bank must sell domestic currency to keep the exchange rate fixed (within limits of ± 1 percent), but as a result it had to take international reserves (US dollars) on board If the domestic currency was overvalued, the central bank must purchase domestic currency to keep the exchange rate fixed, but as a result it lost international reserves 10 Goethe Business School The role of the IMF Surplus countries faced a strengthening of their currencies (revaluation) Deficit countries experienced a weakening (devaluation) The IMF took (and takes) the role of an international lender under certain conditions Loans are given to member countries with balance-of-payment difficulties The IMF has now close to 190 members 11 Goethe Business School IMF as “lender of last resort” A “lender-of-last-resort” operation by the IMF is a two-edged sword: central bank lending during a financial crisis could stabilize the currency and strengthen domestic balance sheets; and it could fend off speculation and prevent contagion But it could also arouse fears of inflation spiraling out of control, and hence cause a further depreciation; and it could increase moral hazard and adverse selection problems and make the crisis worse 12 Goethe Business School The operation of the system As for any fixed-exchange-rate regime, the “price-species-flow” mechanism was also working under the BW-system However, revaluations and devaluations were devices to “let out steam” and to ease economic pressures, and hence to avoid the full price adjustment This was in particular helpful for deficit countries, because internal prices are typically rigid downwards (in particular wages), and a painful deflation could thus be avoided 13 Goethe Business School Problems of the BW system The US-dollar became an international trading and reserve currency, for which the Fed held a monopoly As more and more dollars would be issued (US gold reserves remaining constant), trust in the world currency was expected to weaken (“Triffin Dilemma”) However, initially there was a shortage of international reserves worldwide, although this changed later 14 Goethe Business School Special Drawing Rights (SDR) In order to overcome the apparent shortage of international reserves in the 1960s, the US and other key IMF members had allowed the IMF to issue a paper substitute for gold: “special drawing rights” (SDRs) SDRs function as international reserves, but -unlike gold -- they can (within limits) be issued by the IMF through credit creation SDRs are only being used for official payments among central banks 15 Goethe Business School The end of Bretton Woods The Bretton-Woods agreement lasted until 1971, when it broke down due to institutional and economic asymmetries When the US pursued an inflationary policy during the 1960s and early 1970s, the “lowinflation” Deutsche Mark became an increasingly attractive speculative asset Prices for gold in the free market provided opportunities for arbitrage gains; there were mounting incentives for currency speculation 16 Goethe Business School The end of Bretton Woods One option of surplus countries would have been to follow US inflationary policies (and take on board US dollars without limits!) This opens up unlimited seignorage gains for the issuer of the reserve currency, the US The other option was to revalue For countries that use the dollar as a reserve instrument, their relative wealth position is tied to the exchange rate of international reserves A revaluation of the DM implies a devaluation of the acquired claims in US dollars 17 Goethe Business School Forex market and monetary policy Moreover, an appreciation of the currency entails an increase in export prices for foreigners, and a fall of import prices at home This could trigger higher unemployment “Because surplus countries were not willing to revise their exchange rates upward, adjustment .. did not take place and the BW System collapsed in 1971.” (F. Mishkin) “The ability to conduct monetary policy is easier when a country’s currency is a reserve currency” (F. Mishkin) 18 Goethe Business School The ECU and the ERM The ECU was a weighted average of the currencies of all (initially 9, then 12) member states of the (now) European Union The ERM (“exchange-rate mechanism”) was an arrangement that compelled governments to keep the exchange rate of their currencies within predetermined corridors (± 2.25% or ± 6%) relative to the ECU rate Participation in the ERM was voluntary 19 Goethe Business School The composition of the ECU (1989) Luxemburg (0,30%) France (18,99%) Germany (30,08%) Ireland (1,10%) UK (12,99%) Italy (10,14%) Netherlands (9,40%) Portugal (0,80%) Spain (5,30%) Denmark (2,50%) Belgium (7,60%) Greece (0,80%) 20 Goethe Business School The exchange-rate mechanism (ERM) The national currency is fixed to the ECU A variation of the exchange rate within the predefined “corridor” is allowable Once the exchange rate tends toward the margins of the “corridor”, the central bank is encouraged to intervene (“infra-marginal interventions”) Once the exchange rate moves out of the “corridor”, a central bank intervention is mandatory to bring it back into the “corridor” 21 Goethe Business School International monetary policy coordination There were two (failed) attempts to coordinate exchangerate policies to stabilize the US dollar in the 1980s: the “Plaza” and the “Louvre” accords 22 Goethe Business School Capital controls Capital controls (particularly those on outflows) are typically rejected by economist Controls on capital inflows receive some support and have also been used rather successfully in some countries (Chile and Colombia) Reason: Capital inflows can cause an excessive lending boom, … entailing a painful reversal But controls of capital inflows could also block funds for economic development. It calls for differential treatment according to maturity 23 Goethe Business School The international policy focus is now on … .. improving banking regulation and supervision, and on greater transparency. 24 Goethe Business School The role of a nominal anchor Adherence to a nominal anchor forces a monetary authority to conduct “disciplined” monetary policy A priori publicized self-binding rules imply a strong auto-commitment; can relieve from short-term political pressures; contribute to the predictability of policy and hence stabilize economic behavior; foster confidence building in monetary authorities 25 Goethe Business School The time-consistency problem Economic behavior is influenced by what economic agents expect monetary authorities to do in the future If expectations were to remain unchanged there is the temptation to abuse this fact by attempting to boost the economy through discretionary expansionary monetary policy If expectations will incorporate the expected outcome of such a policy, output will not be higher, but inflation will! A monetary anchor acts as self-binding rule 26 Goethe Business School Exchange-rate targeting Exchange-rate targeting has a long history, including the fixing of the exchange rate to the price of gold Exchange-rate targeting has clear advantages it links the price of traded goods to that found in the anchor country; this might contain inflation; time-inconsistent monetary becomes less of an option; this stabilizes price expectations; it is a simple and transparent rule (“franc fort”) Exchange-rate targeting has been widely used in Europe and world-wide 27 Goethe Business School Disadvantages of exchange-rate targeting Exchange-rate targeting might be create serious problems because the country tying its currency to that of an anchor currency can no longer respond to shocks to its own economy; there could also be shocks applying to the anchor country; these are fully transmitted (the case of Germany after unification); if the anchor country opts for inflation, countries with pegged currencies will “import inflation” it may present opportunities of a one-way bet for speculators (crisis of the EMS of September 1992) 28 Goethe Business School The 1992 ERM crisis: the UK and France The UK did devalue France did not! 29 Goethe Business School The “cost” of pegging The UK had higher growth and less unemployment But its inflation rate increased France had lower growth and more unemployment But its inflation rate was lower 30 Goethe Business School Exchange-rate targeting: For whom? Industrialized countries might have more to lose by exchange-rate targeting than to win In some industrialized countries the central banks is subject to political pressure In this case exchange-rate targeting may prove to be beneficial It also encourages economic integration Contrary to industrialized countries, emerging market countries may not lose much by giving up an independent monetary policy, but it leaves them open to speculative attacks 31 Goethe Business School Can speculation be averted? The currency-board approach: One approach is to back the domestic currency by 100% by a foreign currency (euros, dollars) It means the money supply can only expand when international reserves of a country increase. a strong commitment of monetary policy, which may therefore work instantly in controlling inflation. Currency boards are however not immune against speculation 32 Goethe Business School Currency boards: Examples Recent examples of currency boards include Hong Kong (1983) Argentina (1991) Estonia (1992) and Lithuania (1994) Bulgaria (1997) Bosnia and Herzegovina (1998) Argentina had to abandon the scheme in December 2001 -- with painful social and economic repercussions 33 Goethe Business School The CFA-zone The CFA franc is the common currency of 14 countries in West and Central Africa, 12 of which are former French colonies The CFA franc has been pegged to the French franc since 1948. Only one devaluation has occurred during the history of the currency peg (January 1994) The French Treasury has the sole responsibility for guaranteeing convertibility of CFA francs into euros, without any monetary policy implication for the ECB 34 Goethe Business School Can speculation be averted? Dollarization: Another approach is to abandon a national currency altogether and to adopt a foreign currency (e.g. US dollars) instead It means a euro or dollar remains a euro or dollar, whether inside or outside the respective currency area. that the country adopting a foreign currency loses potential income through seignorage. However a reversal to a domestic currency always remains an option 35 Goethe Business School “Dollarization”: Examples of countries Andorra East Timor Ecuador El Salvador Kirib ati Kosovo Liechtenstein Marshall Island s Micronesia Montenegro Monaco Nauru Palau Panama San Marino Tuvalu Vatican City euro (formerly French franc, Spanish peseta), own coins U.S. dollar U.S. dollar U.S. dollar Australian dollar, own coins euro Swiss franc U.S. dollar U.S. dollar euro (partly "DM-ized" since 1999) euro (formerly French franc) Australian dollar U.S. dollar U.S. dollar, own balboa coins euro (formerly Italian lir a), own coins Australian dollar, own coins euro (formerly Italian lir a), own coins 1278 2000 2000 2001 1943 1999 1921 1944 1944 2002 1865 1914 1944 1904 1897 1892 1929 36 Goethe Business School “Dollarization”: Exits Even dollarization does not guarantee a permanent monetary anchoring There is need to a continuing inflow of foreign denominated capital to satisfy domestic demand for money This puts severe strains on the economy There is a large number of exits from a currency zone during recent years: Numerous exits from the ruble zone after the breakdown of the Soviet Union the secession of Slovakia from Czechoslovakia the breakdown of Yugoslavia 37 Goethe Business School Foreign exchange arrangements 38 Goethe Business School Inflation targeting A number of countries has adopted inflation targeting following the lead of New Zealand (1990) Canada (from 1991) the UK (from 1992) Australia (1994) Brazil (1995) In 1990 the Reserve Bank of NZ became fully independent and was committed to the sole objective of price stability The governor of the central bank is held accountable for achieving a predefined inflation goal 39 Goethe Business School Inflation targeting: strategy The strategy consists of publicly announcing a medium-term numerical target for inflation that is well defined; committing the central bank to price stability as the primary (if not sole) policy goal; an information strategy that includes several indicators, not just monetary aggregates increased communication with the public to render monetary policy more transparent; and an increased accountability of the central bank for attaining its inflation target. 40 Goethe Business School Inflation targeting: advantages Inflation targeting enables the central bank to focus on domestic policy objectives, but a stable relationship between money and the price level is not critical for its success; is highly transparent and easily understood; increases the accountability of the central bank because of a numerical target as a benchmark; seems to ameliorate the effects of inflationary shocks (introduction of a GST in Canada; exit of the British pound from the ERM in 1992). There was a one-time price adjustment, but no spiraling up of inflation. 41 Goethe Business School Inflation targeting: disadvantages Inflation targeting is not without problems because inflation cannot be controlled directly and policy outcomes occur only with a time lag; therefore the policy cannot send immediate signals to economic agents; may be too rigid and limit the policy discretion to respond to unforeseen events; it will even out inflation, but might increase output fluctuations 42 Goethe Business School The two pillar strategy of the ECB The strategy of the ECB appears to reconcile monetary targeting with inflation targeting by scrutinizing both monetary growth and a bundle of economic indicators to assess the mediumterm impact on the HICP Contrary to the NZ approach, the ECB may be criticized as being less responsive to public demands for information Less transparency goes hand in hand with less accountability 43 Goethe Business School Reading 10-1: “Wrestling for influence”, The Economist, July 3rd, 2008 44 Goethe Business School That’s it ! Thank you for attending this course I hope you enjoyed it All the best for you private and professional future, and … … good luck for the final exam ! 45 Goethe Business School