McCartney Jenn McCartney Dr. Vadas Gintautas COR405 23 April

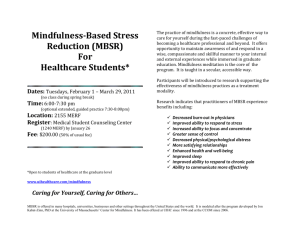

advertisement

McCartney 1 Jenn McCartney Dr. Vadas Gintautas COR405 23 April 2014 Flow and Mindfulness: A Study of Relation Initially the question of how mindfulness and flow relate became of heightened interest from the beginning of COR405. Having an understanding of the use of mindfulness in athletics, psychology, and meditation and a new awareness of flow generated a constant comparison of the two mindsets for the duration of the class. While the text for the course discussed flow’s relation to yoga, direct comparison to mindfulness was overlooked. This lapse in research has perpetuated an interest to further study the relation between flow and mindfulness. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi the author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, theorizes flow, as the mental state at which people are happiest. Flow is defined as the state of mind when a person is fully engaged in an activity with high focus, full participation, and enjoyment (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). Flow occurs during activities in which a person’s interest is captive through complexity with strong supports. These supports include distinct rules, lofty expectations, personal reassurance, and opportunities for one to make decisions (Whalen 1999). Flow is associated with nine characteristics that a person experiences. The characteristics include a balance between the challenge and skill level, concentration on the activity, a merging of awareness and action, concise goals, explicit feedback, feelings McCartney 2 of complete control over the activity, losing a sense of time passing, absence of selfconsciousness, and lastly an autotelic experience (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi 1999). Mindfulness is defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003). Mindfulness originates from the idea that cognitive, emotional, and sensory experiences occur naturally at their own accord and therefore should be accepted as part of being a human (Gardner & Moore 2004). Renowned Buddhist scholar-monk further describes mindfulness as the following: The mind is deliberately kept at the level of bare attention, detached observation of what is happening within us and around us in the present moment. In the practice of right mindfulness the mind is trained to remain in the present, open, quiet, and alert, contemplating the present event. All judgments and interpretations have to be suspended, or if they occur, just registered and dropped… To practice mindfulness is thus a matter not so much of doing but of undoing: not thinking, not judging, not associating, not planning, not imagining, not wishing. All these “doings” of ours are modes of interference, ways the mind manipulates experience and tries to establish its dominance (Bodhi 1994). One of the most distinct differences between mindfulness and flow is the awareness of bodily sensations. For a person to be in a state of mindfulness the individual needs to gain awareness during their actions of the various sensations and thought processes occurring within the moment (Neale 2007) as such experiences are an integral part of the human condition (Gardner & Moore 2004). Because of the heightened awareness and acceptance of emotions and sensations, mindfulness has become a popularized means of treating psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders due to sufferers having an increased reaction and detection of such responses (Kabat-Zinn 2003). McCartney 3 In 1956 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi studied the brain’s ability to focus on only 126 bits of information per second. A single conversation takes up 40 bits per second, which is a third of the brains capacity. Csikszentmihalyi’s research further explains why when a person is fully engrossed in an activity during flow the person loses awareness of bodily needs, time passing, and other distractions. This occurs because the brain is using maximum bits of information per second while in flow leaving no room for attention directed elsewhere (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). This very absence is one of the key differences between flow and mindfulness. Within athletics, mindfulness is often used to improve the ability to focus on the activity, however the emphasis of noticing bodily sensations and thought processes may have counter reactions if the goal is to block the emotions. When an individual experiences an overload of cognitive activity such as performance anxiety, focusing on such emotions can have a paradoxical effect in terms of self-control or thought-blocking (Aherne, Moran, & Lonsdale 2011). An example of such a state would be a basketball player becoming aware of his anxiety to make the free throw. Awareness to such anxiety may in turn worsen the basketball player’s ability momentarily and cause him to miss the shot. The key to mindfulness working in athletics without a paradoxical effect occurring is the training of concentration on the present moment rather than looking into the next steps or processes. The idea is to accept the present moment for what it is rather than judging it or trying to change the moment (Aherne, Moran, & Lonsdale 2011). In the example of the basketball player, acceptance would need to be attained of the anxiety, McCartney 4 rather than a focus on the emotion. The player would need to accept the emotion for what it is, just an emotion. The similarity between flow and mindfulness is highlighted in the emphasis of being in the moment (Aherne, Moran, & Lonsdale 2011). Kee and Wang (2008) studied the relationship between athletes being aware of their emotions nonjudgmentally and their ability to attain a flow state. An analysis was examined between 182 college athletes to study the relationship between flow, mindfulness, and cognitive ability. The results of the study indicated athletes who engage in mindfulness more often had higher rates of flow. The limitations of the study indicate an absence of depicting whether or not mindfulness directly caused athletes to experience flow (Kee & Wang 2008). Further research has followed Kee and Wang’s initial study. Case studies performed by Gardner and Moore (2004) and Aherne, Moran, and Lonsdale (2011) indicates athletes who engage in mindfulness training experience increased peak performance (Aherne, Moran, & Lonsdale 2011). Peak performance and flow are connected through the idea that optimal performance is an outcome of being in flow and thus increased mindfulness equates to a greater likelihood of experiencing flow (Jackson & Roberts 1992). The connection between flow and mindfulness is not just limited to athletics. Satinder Dhiman (2012) paraphrases the connection as the following: …to enjoy this felicitous state of creative fulfillment or flow, one has to achieve certain measure of awareness regarding the contents of one’s consciousness. Mindfulness as a meditative practice can help tremendously in raising the awareness level of the contents of the mind. By being mindfully aware of one’s inner and outer world, one notices new things, which in turn helps one become more creative and alive. Thus, mindfulness McCartney 5 can serve as a basis of creativity, flow, and meaningful engagement with life in it’s myriad of manifestations. With any research subject, further investigation needs to occur to gain a better understanding of the connection between flow and mindfulness. Studying applications further such as athletics, the arts, education and other disciplines, in relation to whom and how mindfulness training betters the likelihood of flow being attained, may enable greater optimal performance for individuals (Aherne, Moran, & Lonsdale 2011). Lastly, because mindfulness training is often utilized for sufferers of depression and anxiety (Kabat-Zinn 2003) and flow is theorized as the mental state at which people are happiest (Csikszentmihalyi 1990) it only makes sense to further research the connection. It is reasonable to presume if mindfulness can aid in the ability to achieve flow, sufferers of psychological ailments may have a new means of reaching a greater state of happiness. In turn this may mean flow has the ability for not only optimal performance in activities, but in life as a whole. McCartney 6 Works Cited Aherne, Cian, Aiden P. Moran, and Chris Lonsdale. "The Effect of Mindfulness Training on Athletes' Flow: An Initial Investigation." The Sports Psychologist 25 (2011): 177-189. Print. Bodhi, B. The Noble Eightfold Path: Way to Ending Suffering. Onalaska, WA: BPS Pariyatti. 1994. pdf. Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row, 1990. Print. Dhiman, Satinder. Mindfulness and the Art of Living Creatively: Cultivating a Creative Life by Minding our Mind. Journal of Social Change. 4(1). 24-33. 2012. pdf. Gardner, F.L., & Moore, Z.E. Mindfulness and Levels of Stress: A Comparison of Beginner and Advanced Hatha Yoga Practioners. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(4), 931-941. 2004. pdf. Jackson, S.A., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow in Sports: The Key to Optimal Experience and Performances. Human Kinetics. 1999. pdf. Jackson, S.A., & Roberts, G.C. Positive Performance States of Athletes: Towards a Conceptual Understanding of Peak Performance. The Sport Psychologist. 6, 156171. 1992. pdf. Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based Intervention in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144-156. 2003. pdf. Kee, Y.H. & Wang, C.K.J. Relationships Between Mindfulness, flow dispositions and mental skills adoption: a cluster analytic approach. Psychology of Sports and Exercise. 9, 393-411. 2008. pdf. Neale, M. Mindfulness Meditation: An Integration of Perspectives from Buddhism, Science, and Clinical Psychology. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B. The Sciences and Engineering, 67. 10-b, 6070. 2007. pdf. Whalen, Samuel P. “Finding Flow at School and at Home: a Conversation with Mihaly Csikszentmihali.” Journal of Secondary Gifted Education 10.4 (1999): 161. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Apr. 2014.