Bacon's Rebellion America's First Revolution?

advertisement

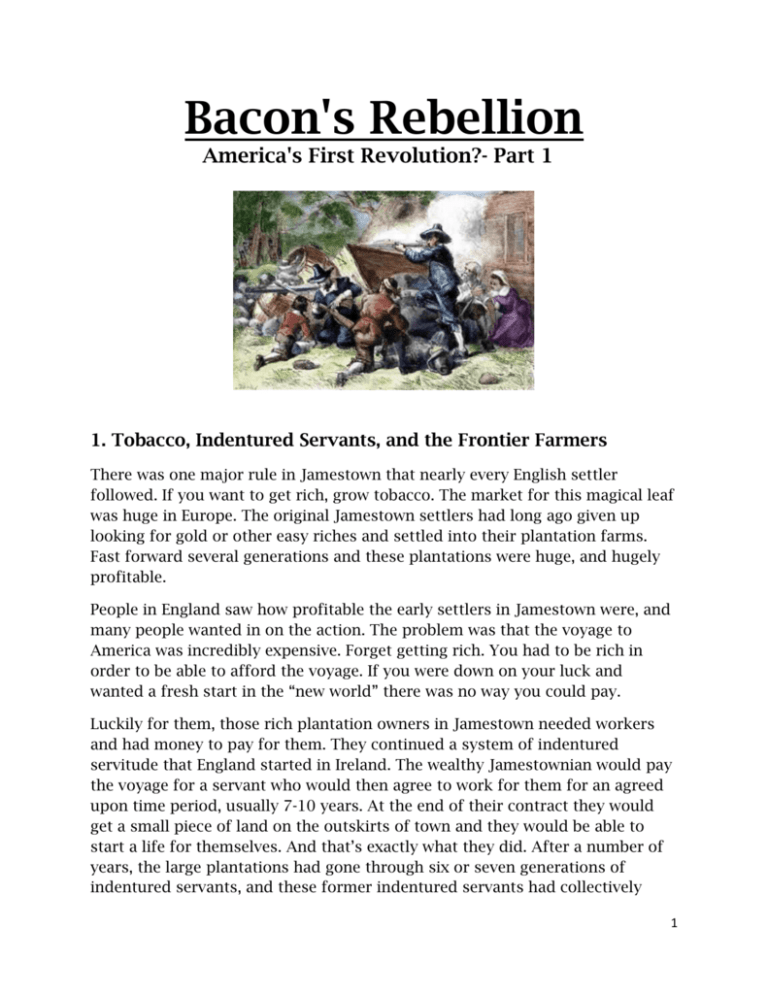

Bacon's Rebellion America's First Revolution?- Part 1 1. Tobacco, Indentured Servants, and the Frontier Farmers There was one major rule in Jamestown that nearly every English settler followed. If you want to get rich, grow tobacco. The market for this magical leaf was huge in Europe. The original Jamestown settlers had long ago given up looking for gold or other easy riches and settled into their plantation farms. Fast forward several generations and these plantations were huge, and hugely profitable. People in England saw how profitable the early settlers in Jamestown were, and many people wanted in on the action. The problem was that the voyage to America was incredibly expensive. Forget getting rich. You had to be rich in order to be able to afford the voyage. If you were down on your luck and wanted a fresh start in the “new world” there was no way you could pay. Luckily for them, those rich plantation owners in Jamestown needed workers and had money to pay for them. They continued a system of indentured servitude that England started in Ireland. The wealthy Jamestownian would pay the voyage for a servant who would then agree to work for them for an agreed upon time period, usually 7-10 years. At the end of their contract they would get a small piece of land on the outskirts of town and they would be able to start a life for themselves. And that’s exactly what they did. After a number of years, the large plantations had gone through six or seven generations of indentured servants, and these former indentured servants had collectively 1 gotten a lot of land. They did exactly what the plantation owners did: They grew tobacco. Lots of it. These were still small plots of land, so they were not rich like the plantation owners in Jamestown, but suddenly, Jamestown had a huge group of middle class farmers living out near the frontier. The problem for the plantation owners was this: While no single plot of land was large enough to get rich on, there were so many of them that together they added A LOT of tobacco to the market. This extra tobacco lowered the price for all tobacco farmers and suddenly the wealthy plantation owners were not making as much money as they wanted to. So they were not too happy with this new class of small farmers. They also were competing with newer colonies like Maryland and the Carolinas, as well as the West Indies. Hailstorms, floods, and hurricanes had also devastated the colonies and their crops. 2. The Frontier Things were also hard for these small (former indentured servants) farmers. They were out on the frontier, away from the protection of Jamestown. When you think of the “frontier” you might imagine a line drawn on a map with European “civilization” on one side, and the Native “wilderness” on the other. (We of course know that the Europeans were often “uncivilized” and the Natives were hardly savages.) It was a division between two different cultures who struggled to see eye to eye, but it wasn’t exactly a line. The frontier was a vast 2 area where both cultures mixed and often clashed. They were neighbors and trading partners. In many cases they were friends, and in a few cases they even intermarried and lived their lives together. As trade between the English and the various Native American tribes became a stronger part of both economies, simply leaving each other alone was no longer an option. Both sides depended on this trade for their survival. The frontier also didn’t stay put in one place. It moved around as people from both cultures spread out. While the colony was now at peace with the defeated Powhatans, other Native American tribes were not exactly pleased with the English colonies spreading out. The Doeg and Susquehanna natives were upset about the settlers spreading out into their land. Additionally, Europeans arriving in Virginia who hoped to find cheap land, were upset to find the most valuable land in Jamestown off-limits. They had to settle on the frontier with the small farmers. As more and more settlers from England and former indentured servants settled onto the frontier, land became a major source of tension. Living on this land often brought them into contact, and conflict, with the natives who lived there. This tension exploded in July 1675. A frontier farmer named Thomas Matthews traded for some goods with the Doeg Natives, but he ended up not paying them. The Doegs retaliated by raiding Thomas Matthews’ plantation. As they were stealing several hogs as payment, several Doegs were killed in the fracas. 3 This hadn’t been the first such Indian conflict, but tensions now reached a flashpoint. In retaliation, colonists struck back. Nathaniel Bacon, a planter, rose as the natural leader of the outraged Virginians. Leading a ragtag group of angry farmers, slaves and indentured servants who had escaped from their masters, Bacon assaulted the Indians. Unfortunately, the Virginians attacked Susquehannocks—the wrong tribe. The Susquehannocks struck back, killing 36 colonists to avenge their previous attack. These attacks led what was a personal issue with Thomas Matthews’s deal gone wrong, and blew it up into a series of large scale raids between the Natives and English on the frontier that made life very dangerous for everyone on the frontier. 3. Power Struggle Between Two Strong Personalities Born in Suffolk, England on Jan. 2, 1647, Nathaniel Bacon, Jr. had been called a troublemaker and schemer at home. His father, Thomas, sent him to the colonies in about 1672. He thought that the “wild” life in the colonies would force his son to grow up and stop his rabble-rousing. His financial support allowed the 25-year-old man to purchase two estates on the James River. Intelligent and well-spoken, Bacon was popular, and quickly found his support in the growing masses of small farmers on the frontier. Coincidentally, Bacon was also related to the other chief player in the drama through the marriage of his cousin Lady Berkeley, Sir William Berkeley’s wife. Berkeley respected Nathaniel Bacon as a fellow aristocrat when the young man arrived in Virginia, giving him land for his plantation in Jamestown, and a seat on the Council. Sir William Berkeley (pronounced BARK-lee) was the leader of the Jamestown government and the official representative for the English government. He was seventy years old during Bacon’s Rebellion, and had acquired a lifetime of experience, both as a soldier during the Anglo-Powhatan wars, as well as his government experience for the thirty years leading up to the showdown with his cousin. But there was a darker side to the loyalist. He stated memorably, “I thank God there are no free schools, nor printing, and I hope we shall not have these hundred years; for learning has brought disobedience into the world, and printing has divulged them and libels against the best governments. God keep 4 us from both!” (What does this quote mean? How did Berkeley feel about democracy? About the lower classes?) Governor Berkeley, sharply condemned the attacks, seeing a dangerous escalation of tensions as something that could destroy everything the colony was trying to build in the new world. Berkeley was probably outraged as he rode into Bacon’s homestead with 300 militia. Bacon, wisely, fled into the forest with some 200 volunteers, perhaps searching for a better meeting place. Frustrated, the governor issued two petitions that declared Nathaniel Bacon a rebel but pardoned the volunteer Indian fighters if they returned home peacefully. Bacon would be given a fair trial for his disobedience, Berkeley stated, but would certainly be relieved of his Council seat. Bacon responded by attacking an encampment of Occaneechee Indians on the Roanoke River between Virginia and North Carolina. The Occaneechee were enterprising people who were embroiled in their own squabble with the Susquehannocks. Once again, Bacon and his militia might have had a legitimate gripe, but attacked the wrong Indians. He would make this mistake again and again. Did he understand that these were separate tribes who had nothing to do with his complaints against the Doegs and Suasuehannocks? Did he care? Was he using his new fame and militia to wage a larger war against all Native Americans? What is clear is that Bacon was not only making enemies out of all Native American tribes in the area, but also making enemies of the Berkeley’s government who was desperately trying to maintain peace with the Native Americans. 5 4. Berkeley’s Compromise Becomes an Epic Fail Governor Berkeley immediately investigated the Doeg and Susquehannock attacks, hoping to preserve friendship with the tribes while calming the settlers down. But, when he set up a meeting between Bacon’s militia and the Susquehannocks, several tribal chiefs were murdered. Bacon’s irresponsible attacks on Native Americans were getting out of hand. Bacon then disregarded Berkeley’s direct orders, and seized friendly Appomattox Indians for supposedly stealing corn. Berkeley officially reprimanded Bacon, but he also knew that he had to make some compromises in order to calm down Bacon’s militia of frontiersmen before things exploded. (It is easy to paint Bacon’s militia as an angry racist mob, but remember that their families and farms were being attacked by Natives. It was still very dangerous to live on the frontier, and Berkeley’s government didn’t seen very eager to do anything about it.) He now demanded that Berkeley give him a commission of soldiers under his command in order to fight the Native Americans. While Berkeley didn’t give into Bacon’s demands, he did try several things to appease the frontier farmers. Berkeley took the powder and ammunition away from nearby tribes, and stopped trading weapons to them. Berkeley set a policy that distinguished between “good” Indians and “bad” Indians. The commission declared war on the “bad” Indians (while maintaining trade with the “good” Indians.) He also created a defensive zone around the settlements with series of military forts built along the frontier. The problem with these forts was that they were built in places that didn’t actually protect the frontier. The construction of the forts also led to high taxes to support the soldiers and resentment from the colonists that had to pay for it. The Long Assembly oversaw trading to make sure that there wasn’t any unnecessary conflict with the natives and ensured the Indians didn’t receive arms and ammunition. It limited trading to the “good” Indians commission was created to and said which colonists were allowed to trade with them. These traders, not coincidentally, were wealthy supporters of the governor. Independent traders, who had traded with the Indians for years, were no longer allowed to continue. Nathaniel Bacon was not one of the traders favored by this deal. You can imagine why he would be upset at being left out while Berkeley and his friends could continue to get rich off of trading with the Indians. Bacon thought this was another example of Berkeley favoring the natives while abandoning the 6 farmers on the frontier. Bacon was also angry that the governor denied him a commission in the local militia, and he had to settle for an unofficial appointment as “General” by local volunteer Indian fighters. Bacon refused Berkeley’s order to disband his 500 person militia, and marched to the falls of the James River. On May 29, Governor Berkeley declared that everyone who failed to return would be termed rebels. Many of Bacon’s men—land owners whose property could be confiscated—heeded the declaration and disbanded. Bacon, left with just 57 loyalists, continued upriver. With their provisions nearly exhausted, the band stumbled into the Occaneechee tribe led by Persicles in its fort on an island in the north branch of the James River. Bacon tried to buy supplies from the Occaneechees, but the tribe put them off for days. As the last of the food gave out, Bacon’s men waded across a branch of the river to the fort. When one of his men was shot, Bacon began to fear that the Occaneechees were plotting with Berkeley. The rebels stormed the fort, blew up the Indians’ supply of guns and powder and killed 150 people. Many of them were defenseless men, women and children. The dead included Persicles and his wife and children. Three of Bacon’s party also lost their lives in the two-day fight before the small band dragged themselves back to their homes. Bacon claimed that his defeat of the Occaneechees was a major victory, and the news of the victory was spread throughout the frontier counties. Bacon and his militia were seen as heroes. He was soon elected to the House of Burgesses in defiance of Governor Berkeley’s proclamations. When he again returned to Jamestown to take his seat in the assembly, the Governor opened fire on the ship from the fort’s guns and took Bacon as a prisoner. 7 Bacon was taken to Governor Berkeley. The old man exclaimed, “Now I behold the greatest Rebel that ever was in Virginia!” He asked, “Mr. Bacon, do you continue to be a gentleman? And may I take your word? If so you are at liberty upon your parole.” Bacon was set free, not because of the Governor’s goodwill (he had once told Bacon’s wife she would see her husband hanged) but because to do otherwise could set the entire colony upon revenge. Bacon’s companions who had been arrested, however, were kept in jail. 5. Bacon Gets Double-Crossed Members of the new Assembly—including the duly elected Nathaniel Bacon— gathered in Jamestown on June 5. Berkeley began again, “If there be joy in the presence of the angels over one sinner that repenteth, there is joy now, for we have a penitent sinner come before us. Call Mr. Bacon.” Bacon was then forced to kneel in front of the burgesses and confess his offense, and to beg the pardon of God, the King and the Governor. To this, Berkeley exclaimed three times, “God forgive you, I forgive you.” He then said, “Mr. Bacon, if you will live civilly but to the next quarter court, I’ll promise to restore your place there,” pointing to Bacon’s seat. Bacon’s election was immediately restored and he was finally promised a commission to go out against the Indians. Bacon, believing that his work was done, left Jamestown unaccompanied. What he didn’t know was that Berkeley planned on double crossing him as soon as he left. The commission of soldiers didn’t arrive. Governor Berkeley, believing all was quiet and that his pardon wasn’t morally binding, issued secret warrants to seize Bacon. When they learned he was once more a fugitive, his followers “sett their throats in one common key of Oathes and curses and cried aloud, that they would either have a Commission…or else they would pull down the Towne.” Rumors reached Jamestown on June 22nd that Bacon was approaching at the head of 500 very angry men. The ragtag army was made up of weatherbeaten frontiersmen, planters sunk deeply in debt, former indentured servants whose release from servitude brought little relief. There was no moderation and little reason in the mass of rebels. Berkeley summoned the York “train bands” to defend Jamestown against Bacon’s presumed attack. (Train bands were local militia who trained in weekly 8 drills.) Only 100 showed up—late—and half of them were rebel sympathizers. Four guns were dragged to Sandy Bay to cover the narrow neck of land connecting the peninsula to the left bank of the river. Messengers rushed to Jamestown, advising of the ad hoc army’s approach led by Bacon. In the face of this apparently overwhelming threat, Governor Berkeley dismounted the guns, withdrew the soldiers and retired to the state house. As Bacon approached with his angry mob, Berkeley hid in the state house with the rest of Jamestown’s wealthy elite. Both sides prepared for the confrontation. 9