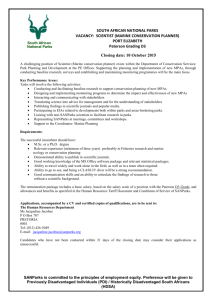

Yaringa Marine National Park

advertisement