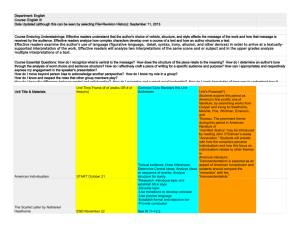

Culture and R 2 - Koç University | College of Administrative

advertisement