MODERN AUDITING

7th Edition

William C. Boynton

California Polytechnic State

University at San Luis Obispo

Raymond N. Johnson

Portland State University

Walter G. Kell

University of Michigan

Developed by:

Gregory K. Lowry, MBA, CPA

Saint Paul’s College

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

CHAPTER 11

DETECTION RISK AND THE DESIGN OF

SUBSTANTIVE TESTS

Determining Detection Risk

Designing Substantive Tests

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

Special Consideration in Designing

Substantive Tests

Determining Detection Risk

Regardless of whether the auditor chooses to

use quantitative or nonquantitative expressions

of the risk levels, planned detection risk is

determined based on the relationships expressed

in the following model:

DR = AR ÷ (IR x CR)

Evaluating the Planned Level

of Substantive Tests

When evaluating the planned level of substantive tests

for each significant financial statement assertion, the

auditor will consider the evidence obtained from:

1. The assessment of inherent risk.

2. Procedures to understand the business and industry

and related analytical procedures that have been

completed.

3. Tests of controls including:

a. Evidence about the effectiveness of internal

controls gained while obtaining an understanding

of internal controls.

b. Evidence about the effectiveness of internal

controls supporting a lower assessed level of control

risk.

Preliminary Audit Strategy,

Planned Detection Risk, and

Planned Emphasis on Audit Tests

Figure 11-1

Preliminary

Audit

Strategy

Planned

Detection

Risk

Planned

Assurance

Obtained

From

Planned

Level of

Substantive

Tests

A primarily

substantive

approach

emphasizing

detail tests

Low or

very low

Tests of details of

transactions and

balances

Higher level

A lower assessed

level of control

risk

Moderate

or high

Tests of controls

Lower level

A primarily

substantive

approach

emphasizing

analytical

procedures

Low or

very low

Analytical procedures

Higher level

Emphasis on

inherent risk and

analytical

procedures

Moderate

or high

Evidence regarding

inherent risk and

analytical procedures

Moederate or lower level

Specifying Detection Risk for Different

Substantive Tests of the Same Assertion

The term detection risk refers to the

risk that all the substantive tests used

to obtain evidence about an assertion

will collectively fail to detect a

material misstatement. In designing

substantive test, the auditor may want

to specify different detection risk

levels to be used with different

substantive tests of the same

assertion.

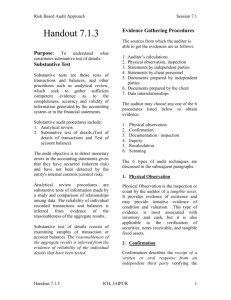

Designing Substantive Tests

The nature of substantive tests refers

to the type and effectiveness of the

auditing procedures to be performed.

1. When the acceptable level of

detection risk is low, the auditor

must use more effective, and usually

more costly, procedures.

2. When the acceptable level of

detection risk is high, less and less

costly procedures can be used.

Designing Substantive Tests

Analytical procedures in audit planning are used to

support top-down audit strategies and to identify

areas of greater risk of misstatement. Analytical

procedures may also be used in the testing phase of

the audit as a substantive test to obtain evidence

about a particular assertion.

AU 329.11, Analytical Procedures (SAS 56),

indicates that the expected effectiveness and

efficiency of analytical procedures depends on the:

1. Nature of the assertion

2. Plausibility and predictability of the relationship

3. Availability and reliability of the data used to

develop the expectation

4. Precision of the expectation

Designing Substantive Tests

Tests of details of transactions primarily involve tracing

and vouching.

Tests of details of balances focus on obtaining evidence

directly about an account balance rather than the

individual debits and credits comprising the balance.

The following illustrates how the effectiveness of tests of

balances can be tailored to meet difference detection

risk levels for the valuation or allocation assertion for

cash in bank:

DETECTION RISK

High

Moderate

Low

Very Low

TESTS OF DETAILS OF BALANCES

Scan client-prepared bank reconciliation and verify

mathematical accuracy of reconciliation.

Review client-prepared bank reconciliation and verify major

reconciling items and mathematical accuracy of reconciliation.

Prepare bank reconciliation using bank statement obtained from

client and verify major reconciling items and mathematical

accuracy.

Obtain bank statement directly from bank, prepare bank

reconciliation, and verify all reconciling items and mathematical

accuracy.

Designing Substantive Tests

An accounting estimate is an approximation of a

financial statement element, item, or account in the

absence of exact measurement.

Tests of accounting estimates usually involve testing

balances, but usually require unique evidence.

AU 342.07, Auditing Accounting Estimates (SAS 57),

states that the auditor’s objective in evaluating

accounting estimates is to obtain sufficient competent

evidential matter to provide reasonable assurance that:

1. All accounting estimates that could be material to the

financial statements have been developed.

2. The accounting estimates are reasonable in the

circumstances.

3. The accounting estimates are presented in conformity

with applicable accounting principles and are properly

disclosed.

Designing Substantive Tests

The acceptable level of detection risk

may affect the timing of substantive

tests.

1. If detection risk is high, the tests

may be performed several months

before the end of the year.

2. When detection risk for an assertion

is low, the substantive tests will

normally be performed at or near

the balance sheet date.

Designing Substantive Tests

More evidence is needed to achieve a

low acceptable level of detection risk

than a high detection risk.

The auditor can vary the amount of

evidence obtained by changing the

extent of substantive tests performed.

Extent is used in practice to mean the

number of items or sample size to

which a particular test or procedure is

applied.

Relationships among Audit Risk Components and

the Nature, Timing, and Extent of Substantive Tests

Figure 11-2

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

One common type of audit software in use today is

known as generalized audit software. Such software

is adaptable for use by auditors for clients’

computer files produced under a variety of data

organization and processing methods.

The computer can be programmed to select audit

samples according to whatever criteria are specified

by the auditor. These samples can be used for a

variety of purposes.

Another common use of the computer is to test the

accuracy of computations in machine-readable data

files. Tests of extensions, footing, or other

computations may be performed.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

The auditor frequently desires to have the

client data reorganized in a manner that will

suit a special purpose. Similarly, in

performing analytical procedures, the auditor

may utilize the computer to compute desired

ratios and other comparative data.

Audited data resulting from work performed

by the auditor may be compared with

information in the computer records. The

audited data must, of course, first be

converted into machine-readable form.

Illustration of Assertions, Specific Audit Objectives,

and Substantive Tests

Figure 11-3

Assertion

Existence or

Occurrence

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

Inventories included in the

balance sheet physically

exist.

Observe physical inventory

counts.

Obtain confirmation of

inventories at locations

outside the entity.

Additions to inventories

represent transactions that

occurred in the current

period.

Test cutoff procedures for

purchases, movement of

goods through

manufacturing, and sales.

Inventories represent items

held for sale or used in the

normal course of business.

Review perpetual inventory

records, production

records, and purchasing

records for indications of

current activity.

Compare inventories with a

current sales catalog and

subsequent sales and

delivery reports.

Assertion

Completeness

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

Inventory quantities

include all products,

materials, and supplies on

hand.

Observe physical inventory

counts.

Account for all inventory

tags and count sheets used

in making the physical

inventory counts.

Analytically review the

relationship of inventory

balances to recent

purchasing, production,

and sales activities.

Test cutoff procedures for

purchases, movement of

goods through

manufacturing, and sales.

Inventory quantities

include all products,

materials, and supplies

owned by the company that

are in transit or stored at

outside locations.

Obtain confirmation of

inventories at locations

outside the entity.

Analytically review the

relationship of inventory

balances to recent

purchasing, production,

and sales activities.

Test cutoff procedures for

purchases, movement of

goods through

manufacturing, and sales.

Assertion

Rights and

Obligations

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

The entity has legal title or

similar rights of ownership

to the inventories.

Observe physical inventory

counts.

Obtain confirmation of

inventories at locations

outside the entity.

Examine paid vendors’

invoices, consignment

agreements, and contracts.

Inventories exclude items

billed to customers or

owned by others.

Examine paid vendors’

invoices, consignment

agreements, and contracts.

Test cutoff procedures for

purchases, movement of

goods through

manufacturing, and sales.

Assertion

Valuation or

Allocation

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

Inventory records are

accurately compiled and

the totals are properly

included in the inventory

accounts.

Review activity in general

ledger accounts for

inventories and investigate

unusual items.

Verify extensions of

quantities times unit prices

and totals of inventory

records, and agreement

with general ledger.

Trace test counts recorded

during physical inventory

observation to inventory

records.

Reconcile physical counts

to perpetual records and

general ledger balances and

investigate significant

fluctuations.

Inventories are properly

stated at cost (except when

market is lower).

Examine paid vendors’

invoices.

Review direct labor rates.

Test computations of

standard overhead rates

and standard costs, if

applicable.

Examine analyses of

purchasing and

manufacturing standard

cost variances, if

applicable.

Assertion

Valuation or

Allocation

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

Slow-moving, excess,

defective, and obsolete

items included in

inventories are properly

identified.

Inquire of production and

sales personnel concerning

possible excess or obsolete

inventory items.

Examine an analysis of

inventory turnover.

Review industry experience

and trends.

Analytically review the

relationship of inventory

balances to anticipated

sales volume.

Inventories are reduced,

when appropriate, to

replacement cost or to net

realizable value.

Obtain current market

value quotations.

Evaluate net realizable

value.

Assertion

Presentation and

Disclosure

Specific

Audit

Objective

Examples of

Substantive

Tests

Inventories are properly

classified in the balance

sheet as current assets.

Review drafts of the

financial statements.

The basis of valuation is

adequately disclosed in the

financial statements.

Compare the disclosures

made in the financial

statements to the

requirements of generally

accepted accounting

principles.

The pledge or assignment

of any inventories is

appropriately disclosed.

Obtain confirmation of

inventories assigned or

pledged under loan

agreements.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

The auditor’s decisions regarding the design of

substantive tests are required to be documented in the

working papers in the form of written audit programs

(AU 311.09). An audit program is a list of audit

procedures to be performed.

In addition to listing audit procedures, each audit

program should have columns for:

1. A cross-reference to other working papers containing

the evidence obtained from each procedure (when

applicable),

2. the initials of the auditor who performed each

procedure, and

3. the date the performance of the procedure was

completed.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

Audit programs should be

sufficiently detailed to provide:

1. An outline of the work to be

done

2. A basis for coordinating,

supervising, and controlling

the audit

3. A record of the work performed

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

We can construct a general framework for developing

audit programs for substantive tests. Such an approach

is described in Figure 11-5.

The steps listed in the upper portion of Figure 11-5

summarize the application of several important concepts

and procedures explained in Chapters 5 through 10.

2 additional examples of analogous steps in other areas

of the audit are as follows:

1. verifying the totals and determining the agreement of

the general ledger accounts receivable control account

and the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger and

2. verifying the totals and determining the agreement of

a general ledger investment portfolio account and a

spreadsheet listing the details of the related

investments.

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

Complete Audit Planning

1. Identify the financial statement assertions to be

covered by the audit program.

2. Develop specific audit objectives for each category of

assertions.

3. Obtain an understanding of the client’s business and

industry including such items as the client’s business

cycle, management’s goals and objectives,

organizational resources, the entity’s products,

services market, customers, competition, the entity’s

core processes and operating cycle, and the entity’s

investing and financing decisions.

4. Assess inherent risk for the assertion.

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

5. Assess control risk for the assertion based on:

Evidence of the effectiveness of controls gained

while obtaining an understanding of internal

controls.

Evidence of the effectiveness of management

controls or other manual controls over computer

output.

Evidence of the effectiveness of computer control

procedures including manual follow-up.

6. Determine the final level of detection risk for each

assertion consistent with the overall level of audit

risk and applicable materiality level.

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

7. From knowledge acquired from procedures to obtain

an understanding of relevant internal controls,

envision the accounting records, supporting

documents, accounting processes (including the audit

trail), and financial reporting process pertaining to

the assertions.

8. Consider options regarding the design of substantive

tests:

Alternatives for accommodating varying acceptable

levels of detection risk:

Nature — Analytical procedures, Tests of details

of transactions, tests of details of balances,

Tests of accounting estimates

Timing — Interim versus year-end

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

Extent — Sample size

Staffing — Skill and experience of audit staff

Consider how generalized audit software might

make the audit more effective or more efficient.

Possible types of corroborating evidence available:

Analytical, Electronic, Mathematical,

Written Representation, Documentary,

Confirmations, Physical, and Oral

Possible types of audit procedures available:

Analytical procedures, Inquiring, Vouching,

Computer-assisted audit techniques, Inspecting,

Counting, Observing, Confirming, Tracing,

Reperforming

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

Specify Substantive Tests to Be Included in Audit

Program

1. Obtain an understanding of the business and industry

and determine:

a. The significance of the transaction class and

account balance to the entity.

b. Key economic drivers that influence the

transaction class and account balance that are

relevant to evaluating issues of existence,

completeness, valuation and allocation, rights and

obligations, and presentation and disclosure.

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

2. Specify initial procedures to:

a. Trace beginning balance to prior year’s working

papers (if applicable).

b. Review activity in applicable general ledger

accounts and investigate unusual items.

c. Verify totals of supporting records or schedules to

be used in subsequent tests and determine their

agreement with general ledger balances, when

applicable, to establish a tie-in of detail with

control accounts.

3. Specify analytical procedures to be performed.

4. Specify tests of detail of transactions to be performed.

5. Specify tests of detail of balances to be performed.

General Framework for Developing Audit

Programs for Substantive Tests

Figure 11-5

6. Specify tests of detail of balances involving

accounting estimates to be performed.

7. Consider whether there are any special requirements

or procedures applicable to assertions being tested in

the circumstances such as procedures required by

SASs or by regulatory agencies that have not been

included in (3) and (4) above.

8. Specify procedures to determine conformity of

presentation and disclosure with GAAP.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

In an initial engagement, the detailed

specification of substantive tests in

audit programs is generally not

completed until after the auditor

obtains an understanding of the

business and the industry it operates

in, the study and evaluation of internal

control has been completed, and the

acceptable level of detection risk has

been determined for each significant

assertion.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

2 matters requiring special consideration

in designing audit programs for initial

audits are:

1. determining the propriety of the

account balances at the beginning of

the period being audited, and

2. ascertaining the accounting principles

used in the preceding period as a basis

for determining the consistency of

application of such principles in the

current period.

Developing Audit Programs for

Substantive Tests

In a recurring engagement, the auditor

has access to audit programs used in the

preceding period(s) and the working

papers pertaining to those programs. In

such cases, the auditor’s preliminary

audit strategies are often based on a

presumption that the risk levels and

audit programs for substantive tests

used in the previous period will be

appropriate for the current period.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

Traditionally, tests of details of balances have

focused more on financial statement assertions that

pertain to balance sheet accounts than on income

statement accounts. This approach is both efficient

and logical because each income statement account

is inextricably linked to one or more balance sheet

accounts. Examples include the following:

BALANCE

SHEET

ACCOUNT

Accounts receivable

Inventories

Prepaid expenses

Investments

Plant assets

Intangible assets

Accrued payables

Interest-bearing liabilities

RELATED

INCOME STATEMENT

ACCOUNT

Sales

Cost of sales

Various related expenses

Investment income

Depreciation expense

Amortization expense

Various related expenses

Interest expense

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

Analytical procedures can be a powerful

audit tool in obtaining audit evidence about

income statement balances. This type of

substantive testing may be used directly or

indirectly. Direct tests occur when a

revenue or expense account is compared

with other relevant data to determine the

reasonableness of its balance. For example,

the ratio of sales commissions to sales can

be compared with the results of prior years

and budget data for the current year.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

Additional examples involving

comparisons with nonfinancial

information associated with the

underlying business activity are

illustrated in the following table:

ACCOUNT

ANALYTICAL PROCEDURE

Hotel room revenue

Tuition revenue

Number of rooms x Occupancy rate x Average room rate.

Number of equivalent full-time students x Tuition rate for a

full-time student.

Wages expense

Average number of employees per pay period x Average pay per

Period x Number of pay periods.

Gasoline expense

Number of miles driven ÷ Average miles per gallon x Average per

Gallon cost.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

When the evidence obtained from analytical

procedures and from tests of details of related balance

sheet accounts do not reduce detection risk to an

acceptably low level, direct tests of details of

assertions pertaining to income statement accounts

are necessary. This may be the case when:

1. Inherent risk is high. This may occur in the case

of assertions affected by nonroutine transactions

and management’s judgments and estimates.

2. Control risk is high. This situation may occur

when (1) related internal controls for nonroutine

and routine transactions are ineffective or (2) the

auditor elects not to test internal controls.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

3. Analytical procedures reveal unusual relationships

and unexpected fluctuations. These circumstances

are explained in a preceding section.

4. The account requires analysis. Analysis is usually

required for accounts that (1) require special

disclosure in the income statement, (2) contain

information needed in preparing tax returns and

reports for regulatory agencies such as the SEC, and

(3) have general account titles that suggest the

likelihood of misclassifications and errors.

Accounts requiring separate analysis generally include:

Legal expense and professional fees

Maintenance and repairs

Travel and entertainment

Officers’ salaries and expenses

Taxes, licenses, and fees

Rents and royalties

Contributions

Advertising

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

The auditor should identify related party

transactions in audit planning. These types

of transactions are a concern to the auditor

because they may not be executed on an

arm’s-length basis. The auditor’s objective

in auditing related party transactions is to

obtain evidential matter as to the purpose,

nature, and extent of these transactions and

their effect on the financial statements. The

evidence should extend beyond inquiry of

management.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

AU 334.09, Related Parties, indicates that substantive

tests should include the following:

1. Obtain an understanding of the business purpose of

the transaction.

2. Examine invoices, executed copies of agreements,

contracts, and other pertinent documents, such as

receiving reports and shipping documents.

3. Determine whether the transactions has been

approved by the board of directors or other

appropriate officials.

4. Test for reasonableness the compilation of amounts

to be disclosed, or considered for disclosure, in the

financial statements.

Special Considerations in

Designing Substantive Tests

5. Arrange for the audits of intercompany account

balances to be performed as of concurrent dates,

even if the fiscal years differ, and for the

examination of specified, important, and

representative related party transactions by the

auditors for each of the parties, with appropriate

exchange of relevant information.

6. Inspect or confirm and obtain satisfaction

concerning the transferability and value of

collateral.

Summary of Audit Tests

Figure 11-6

Tests

Of

Controls

Substantive

Tests

Types

Tests of management controls

or other manual controls over

computer output.

Tests of computer controls.

Tests of manual follow-up.

Analytical procedures.

Tests of details of transactions.

Tests of details of balances.

Purpose

Determine effectiveness of

design and operation of internal

control structure policies and

procedures.

Determine fairness of

significant financial statement

assertions.

Nature of

test measurement

Frequency of deviations from

control structure policies and

procedures.

Monetary errors in transactions

and balances.

Tests

Of

Controls

Substantive

Tests

Applicable

audit

procedures

Inquiring, observing,

inspecting, reperforming, and

computer-assisted audit

techniques.

Same as tests of controls, plus

analytical procedures, counting,

confirming, tracing, and

vouching.

Timing

Primarily interim work.

Primarily at or near balance

sheet date.

Audit risk

component

Control risk.

Detection risk.

Primary fieldwork

standard

Second.

Third.

Required by

GAAS

No.

Yes.

CHAPTER 11

DETECTION RISK AND THE DESIGN OF

SUBSTANTIVE TESTS

Copyright

Copyright 2001 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights

reserved. Reproduction or translation of this work

beyond that permitted in Section 117 of the 1976

United States Copyright Act without the express

written permission of the copyright owner is

unlawful. Request for further information should

be addressed to the Permissions Department, John

Wiley & Sons, Inc. The purchaser may make backup

copies for his/her own use only and not for

distribution or resale. The Publisher assumes no

responsibility for errors, omissions, or damages,

caused by the use of these programs or from the

use of the information contained herein.