Morphemes, morpheme classification, inflectional

advertisement

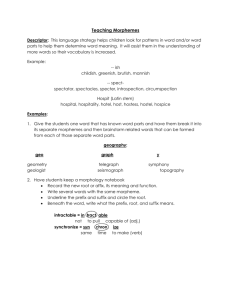

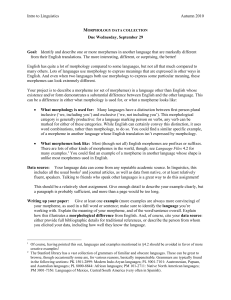

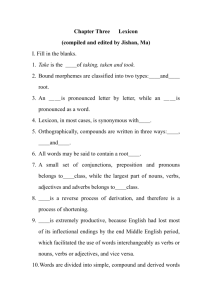

Morphemes, morpheme classification, inflectional and derivational morphology June 5, 2014 What is a word?? https://twitter.com/nixicon Morphology morphology: subfield of linguistics that studies… • words, their structure, and how they are put together out of their composing parts • rules that determine how words are put together using these component parts • how meaning of a complex word is related to the meaning of its parts • how individual words of a language are related to other words of the language in terms of their morphological structure morphophonology: study of the interaction between morphology and phonology. More on morphophonology is coming up next week! Sound and meaning In general, a word’s meaning or usage cannot be predicted from the speech segments that make up the word, e.g.: English Polish French Japanese [dag] [pjɛs] [ʃjɛ̃] [inu] But there are types of words in which sound and meaning are more closely tied, e.g. onomatopoeia: word that (supposedly) imitates natural sounds bam! fizz woof a-choo! Sound and meaning Sound and meaning Look at the two shapes. How would you pair these shapes with the following words? Bouba Kiki sound symbolism: the idea that vocal sounds carry meaning in and of themselves: slip slide, slurp, slither, slime, slug… but slave, slit, slow little, teeny, cutey, Johnny, sweety… but bleed, grip, zombie Sound and meaning But once we know the meanings of certain words, we CAN predict the meanings of other words, because word meaning is often compositional, e.g.: rapid rapidly drink drinkable blue blueish bride, Godzilla bridezilla And yet, the meanings of many phrases and expressions are NOT compositional: • idioms: to kick a bucket, to be a party pooper • collocations: white wine/noise/man • proverbs: It’s no use crying over spilled milk. *It’s no use crying over a broken plate. “Jennifer is a Party Pooper” http://youtu.be/gjwofYhUJEM Word vs. phoneme morpheme: smallest meaningful unit of language and a building block of words (cf. phoneme). Also, a morpheme is identifiable from one word to another. peg and beg are two morphemes with distinct meanings, differentiated by the phonological feature [+/‐voice] and contrastive phonemes /p/ and /b/. But /p/ and /b/ on their own do NOT carry any meaning! Anybody want a peanut? Anybody want some peanuts? Anybody want some peanuts? *Anybody want some –s? Word vs. phoneme In order for something to be a word, it must: • • • • • have meaning have at least one morpheme be able to move relatively freely in a sentence (a word is a free morpheme) usually be inserted between two other words, but not inside of another word have one primary stress Morphemes that canNOT freely occur in a sentence (and that attach to another word) are bound morphemes, ex. –s, – er, –im. Bound morphemes are also called affixes. free morphemes English: a, sweet, camel, library Spanish: y, casa, cucaracha bound morphemes -dis, -ish, -ness, -zilla, prein- (inútil), -s (casas), o (puedo) Morpheme classification (a) read‐able hear‐ing en‐large perform‐ance white‐ness dark‐en seek‐er (b) leg‐ible audi‐ence magn‐ify rend‐ition clar‐ity obfusc‐ate applic‐ant What about words like…? cranberry huckleberry The meaning of the words in (b) and (a) are similar, but roots in (a) are free morphemes, while roots in (b) are bound morphemes! loganberry raspberry There are no words like cran, huckle, logan, and rasp, or at least not with the relevant meaning. Words like cranberry are compounds: complex words consisting of two roots, one of which is bound! Morphemes like cran and logan are often called cranberry morphemes. Morpheme classification Words that consist of a single morpheme are classified as simple words. berry drama with swim restaurant cry cute of wombat Words that consist of more than one morpheme are classified as complex words. berry-s over-drama-tic house-keep-er swim-er restaurant cry-ing cute-ish anti-dis-establish-ment wombat-s Morpheme classification root: morpheme (usually free) that plays a central role, to which all other morphemes attach. Roots usually contribute the greatest meaning component to the resulting word, e.g.: jump + able = jumpable (can be jumped) liquid + ify = liquify (to turn into liquid) dog + s = dogs (more than one dog) affix: bound morpheme that attaches itself to a root. Affixes are further subdivided into: overdramatic prefix root suffix base: that to which the affix is attaching; can be a bare root or an already affixed form stem: the bare root that never changes Practice! With a partner, complete exercise 1 on the exercise sheet. Morpheme classification infix: morpheme that gets inserted INSIDE the root instead of going to its left or right edge! Kharia (India) bhore ‘be full’ t͡ʃuwe ‘leak’ bhobre ‘fill’ t͡ʃubwe ‘cause to leak’ Bontoc (Austronesian, Philippines) fikas ‘strong’ fumikas ‘he is becoming strong’ bato ‘stone’ bumato ‘it is becoming a stone’ English un-freaking-believable Morpheme classification circumfixes: two‐part morphemes that go AROUND the root simultaneously! Chickasow (Oklahoma) lakna ‘it is yellow’ iklakno ‘it isn’t yellow’ palli ‘it is hot’ ikpallo ‘it isn’t hot’ German Lieb ‘love’ glaub ‘believe’ geliebt ‘loved’ geglaubt ‘believed’ Morpheme classification There are other types of morphological processes that are not limited to prefixation and suffixation, e.g. reduplication (root or part of root is repeated). Agta (Austronesian, The Philippines) ma‐wakay ‘lost’ ma‐wakwakay ‘many things lost’ takki ‘leg’ taktakki ‘legs’ mag‐saddu ‘leak’ mag‐sadsaddu ‘leak in many places’ Reduplication is often used iconically: repetition of the phonological material stands for repetition of the events of things (to mean repetitive action or plurality). Ilokano (Austronesian, The Philippines) pusa ‘cat’ puspusa ‘cats’ jojo ‘yoyo’ joj‐jojo ‘yoyos’ English? chit‐chat lovie dovie see‐saw criss cross knock knock bow wow ‘I don’t like him. I like like him!” teeny weeny cray cray Morpheme classification Another non-suffixal processes is zero affixation/conversion: morphological change (usually of lexical class) without any explicit phonological material, e.g. in English: NV a telephone to telephone a friend to friend a Xerox to Xerox VN to look a look to run a run to like a like English words can also change lexical class through: Stress change: per’mit (V.) ‘permit (N.) Final consonant change: prove (V.) proof (N.) defend (V.) defense (N.) Vowel change: sing (V.) song (N.) sit (V.) seat (N.) In English these are exceptional, but some languages use them extensively, e.g.: Hebrew, Arabic use vowel change to signal derivational morphological relationships: Hebrew: sapar ‘barber’ saper verbal root ‘to get a haircut’ Word classes / lexical categories lexical (content) morphemes functional (grammatical) morphemes express general informational content, a meaning that is essentially independent of the grammatical system of a particular language; open class tied to a grammatical function, expressing syntactic relationships between words in a sentence or obligatorily marked categories, such as number or tense; closed class Nouns: London, app, love Verbs: swim, devour, sleep Adjectives: squishy, tiny, meh Adverbs: often, nicely, very Tie elements together grammatically: hit by a truck apples and bananas Express grammatical features, e.g. definiteness, gender, number, tense: She found a/the table vs. *She found table. She found many tables vs. *She found many table. She fixed it yesterday vs. *She fix it yesterday. Prepositions: to, by, from, with Articles: the, a, an Pronouns: Personal: I, he, they Reflexive: yourself, themselves Possessive: my, hers, its Demonstrative: this, these, those Indefinite: each, somebody, both Relative: that, which, what, who Interrogative: where, when, whether Auxiliaries: has, did, will, might Conjunctions: and, but, however Interjections: well, hi, gah! Affixes: re-, -ness, -ly, -ed, -s Word classes / lexical categories Give me a second, I I need to get my story straight My friends are in the bathroom Getting higher than the Empire State My lover, she is waiting for me Just across the bar My seat’s been taken by some sunglasses Asking 'bout a scar fun. “We are young” Practice! With a partner, complete exercise 2 on the exercise sheet. Inflectional vs. derivational morphology Inflectional morphology creates new grammatical forms of the same word, but the core meaning remains the same. Also, inflectional morphology NEVER changes the word’s syntactic/lexical category, e.g.: key (N.) keys (N.) cute (Adj.) cuter (Adj.) Derivational morphology creates new words from old ones. The core meaning might change significantly, and the syntactic category of the word may change too. Also, the new word will require additional inflectional morphology required by the grammar, e.g.: happy (Adj.) unhappy (Adj). blend (V.) blender (N.) blenders derivation inflection Inflectional morphology Inflectional morphology marks grammatical features of words, like plurality or tense. This morphological marking is required by syntax of the language. For example, in English, there are contexts where a verb must carry a 3rd-person singular marker: He goes to school vs. *He go to school Inflections do NOT create new words but rather mark the existing ones for grammar. The meaning of the inflected word is always compositional, or predictable from the meaning of its parts, e.g.: piano (musical instrument) + s (plural) = pianos (more than 1 musical instrument) sweet (sugary flavor) + est (superlative) = sweetest (the most sweet) paint paints painted painting different inflectional variants of the same abstract word (lexeme): PAINT English inflectional morphology tense on verbs aspect on verbs number and person on verbs play vs. played cough vs. coughing she knits number on nouns number on pronouns case on pronouns book vs. books I vs. we, this vs. these they vs. them comparative degree on adjectives superlative degree on adjectives white vs. whiter loud vs. loudest All English inflections are suffixes! English inflectional morphology Some English inflections are irregular, e.g.: tooth teeth go went dive dove or dived child children man men drink drank ox oxen cactus cacti Are these all different allomorphs of the plural morpheme –s and past tense morpheme -ed? • If we use meaning as the basis of our analysis, then YES. • But because of their phonological divergence from –s and –ed, these are usually NOT considered allomorphs. Also, many of the changes involve the word root, not the affix. The phenomenon in which a single lexeme has more than one root is suppletion. English inflectional morphology But what are the plural forms of nouns like…? a pair of a pair of a piece/stick of a piece of some/a lot of a piece of a flock of scissors pants butter furniture knowledge information sheep periphrasis (periphrastic form): use of one or more free morphemes (instead of inflections or derivations) to denote grammatical meaning. Also: more/most intelligent English: of a dog vs. Japanese: いぬの Latin: stēllae Inflectional morphology Some languages have richer inflectional systems than English. Italian: gender Il sole ‘sun’ (masc.) la luna ‘moon’ (fem.) Russian: gender [stul] ‘chair’ (masc.) [taburetka] ‘stool’ (fem.) [sidenje] ‘seat’ (neut.) Inuktitut: number Iglu ‘a house’ Igluk ‘two houses’ (DUAL) Iglut ‘more than two houses’ Polish: case jeż ‘hedgehog’ jeża ‘of a hedgehog’ jeżowi ‘to a hedgehog’ jeża ‘hedgehog (dir. ob.)’ jeżem ‘with a hedgehog’ jeżu ‘about a hedgehog’ jeżu ‘you hedgehog’ NOMINATIVE GENITIVE DATIVE ACCUSATIVE INSTRUMENTAL LOCATIVE VOCATIVE