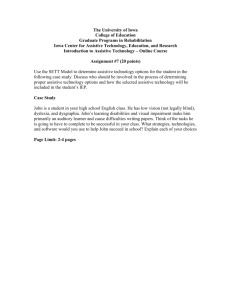

ATOBV9N1 - Assistive Technology Industry

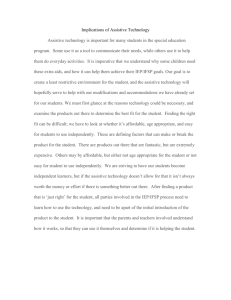

advertisement