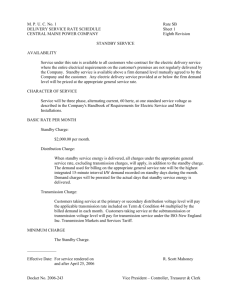

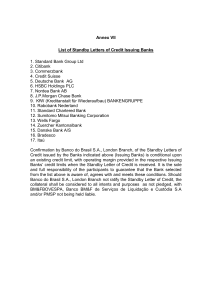

Standby Letters of Credit and the ISP 98

advertisement