21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations

advertisement

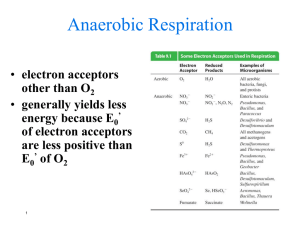

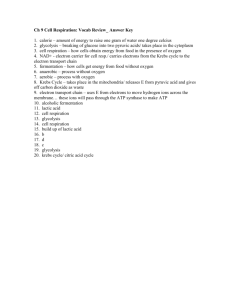

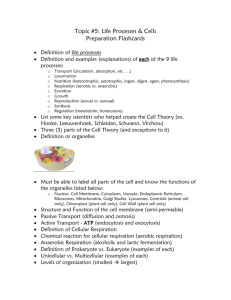

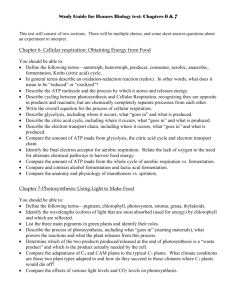

Chapter 21 Metabolic Diversity: Catabolism of Organic Compounds I. Fermentations 21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations 21.2 Fermentative Diversity: Lactic and Mixed-Acid Fermentations 21.3 Fermentative Diversity: Clostridial and Propionic Acid Fermentations 21.4 Fermentations without Substrate-Level Phosphorylation 21.5 Syntrophy 21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations Two mechanisms for catabolism of organic compounds Respiration Exogenous electron acceptors are present to accept electrons generated from the oxidation of electron donors - Aerobic and anaerobic respiration Fermentation Electron donor and acceptor are the same compound Relatively little energy yield 21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations In the absence of external electron acceptors, compounds can be catabolized anaerobically by fermentation ATP is usually synthesized by substrate-level phosphorylation Energy-rich phosphate bonds from phosphorylated organic intermediates transferred directly to ADP Redox balance is achieved by production and secretion of fermentation products The Essentials of Fermentation Figure 21.1 21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations A requirement for most fermentations is that organic intermediates can be generated that contain an energy-rich phosphate bond or a molecule of coenzyme-A Energy-Rich Compounds Involved in SLP Anaerobic Breakdown of Major Fermentable Substrates Figure 21.2 21.1 Fermentations: Energetic and Redox Considerations In many fermentations, redox balance is maintained by the production of molecular hydrogen (H2) H2 production involves transfer of electrons from ferredoxin to H+ by a hydrogenase 21.2 Lactic and Mixed-Acid Fermentations Fermentations are classified by either the substrate fermented or the productions formed A wide variety of organic compounds can be fermented Common Bacterial Fermentations Some Unusual Bacterial Fermentations Lactic Acid Fermentations Lactic acid fermentation can occur by homofermentative and heterofermentative pathways Glucose Fermentation by Homofermentations Figure 21.4 Glucose Fermentation by Heterofermentations Figure 21.4 21.2 Lactic and Mixed-Acid Fermentations The Entner-Doudoroff Pathway A variant of the glycolytic pathway (e.g. Pseudomonas) A widespread pathway for sugar catabolism in bacteria Entner-Doudoroff Pathway Mixed-Acid Fermentations Mixed-Acid Fermentations Generate acids Acetic, lactic, and succinic acids Sometimes also generate neutral products e.g., butanediol Characteristic of enteric bacteria Butanediol Production in Mixed-Acid Fermentations Figure 21.5 21.3 Clostridial and Propionic Acid Fermentations Clostridium species ferment sugars, producing butyric acid Butanol and acetone can also be byproducts The Butyric Acid and Butanol/Acetone Fermentation Figure 21.6 21.3 Clostridial and Propionic Acid Fermentations Some Clostridium species ferment amino acids using a complex biochemical pathway known as the Strickland reaction The Strickland Reaction Figure 21.7 Secondary Fermentations Secondary Fermentation The fermentation of fermentation products C. kluyveri - Ethanol + Acetate → Caproate + Butyrate Propionibacterium - Lactate → Prpionate + Acetate The Propionic Acid Fermentation of Propionibacterium Figure 21.8 21.4 Non-Substrate-Level Phosphorylation Fermentations Fermentations of certain compounds do not yield sufficient energy to synthesize ATP Catabolism of the compound can then be linked to ion pumps that establish a proton or sodium motive force Succinate Fermentation by Propionigenium modestum Figure 21.9a Oxalate Fermentation by Oxalobacter formigenes Figure 21.9b 21.5 Syntrophy Syntrophy A process whereby two or more microbes cooperate to degrade a substance neither can degrade alone Most syntrophic reactions are secondary fermentations Most reactions are based on interspecies hydrogen transfer H2 production by one partner is linked to H2 consumption by the other Syntrophic reactions are important for the anoxic portion of the carbon cycle Syntrophy: Interspecies H2 Transfer H2 consumption affects the energetics of the reaction carried out by the H2 producer, allowing the reaction to be exothermic. Figure 21.10 Syntrophy: Interspecies H2 Transfer Figure 21.10 Energetics of Growth of Syntrophomonas Figure 21.11a Energetics of Growth of Syntrophomonas Disproportionation of crotonate Figure 21.11b II. Anaerobic Respiration 21.6 Anaerobic Respiration: General Principles 21.7 Nitrate Reduction and Denitrification 21.8 Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction 21.9 Acetogenesis 21.10 Methanogenesis 21.11 Proton Reduction 21.12 Other Electron Acceptors 21.13 Anoxic Hydrocarbon Oxidation Linked to Anaerobic Respiration 21.6 Anaerobic Respiration: General Principles In anaerobic respiration electron acceptors other than O2 are used Anaerobic and aerobic respiratory systems are similar But anaerobic respiration yields less energy than aerobic respiration Energy released from redox reactions can be determined by comparing reduction potentials of each electron acceptor Animation: Electon Transport: Aerobic & Anaerobic Conditions Major Forms of Anaerobic Respiration Figure 21.12 21.6 Anaerobic Respiration: General Principles ■ Assimilative metabolism of an inorganic compound (e.g., NO3-, SO42-, CO2) - The reduced compounds are used in biosynthesis ■ Dissimilative metabolism of inorganic compounds - During anaerobic respiration, the reduced products are excreted 21.7 Nitrate Reduction and Denitrification Inorganic nitrogen compounds are the most common electron acceptors in anaerobic respiration 21.7 Nitrate Reduction and Denitrification Most products of nitrate reduction (denitrification) are gaseous (NO, N2O or N2) - Some are NO2- and NH4+ Denitrification is the main biological source of gaseous N2 Steps in the Dissimilative Reduction of Nitrate Figure 21.13 21.7 Nitrate Reduction and Denitrification The biochemical pathway for dissimilative nitrate reduction has been well-studied Enzymes of the pathway are repressed by oxygen Respiration and Anaerobic Respiration (E. coli) Figure 21.14a Respiration and Anaerobic Respiration (P. stutzeri) Periplasmic proteins Figure 21.14c 21.8 Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction Several inorganic sulfur compounds can be used as electron acceptors in anaerobic respiration 21.8 Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction The reduction of SO42- to H2S proceeds through several intermediates and requires activation of sulfate by ATP Activated sulfates Schemes of Assimilative and Dissimilative Sulfate Reduction Figure 21.15b 21.8 Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction Many different compounds can serve as electron donors in sulfate reduction e.g., H2, organic compounds, phosphite Electron Transport and Energy Conservation during Sulfate Reduction Membrane-associated propotein complex Figure 21.16 21.8 Sulfate and Sulfur Reduction Some sulfur-reducing bacteria can gain additional energy through disproportionation of sulfur compounds - S2O32- + H2O → SO42- + H2S 21.9 Acetogenesis Acetogens and methanogens use CO2 as an electron acceptor in anaerobic respiration H2 is the major electron donor for both groups of organisms The Processes of Methanogenesis and Acetogenesis Figure 21.17 21.9 Acetogenesis Acetogens (homo acetogens) Reduce CO2 to acetate by the acetyl-CoA pathway, a pathway widely distributed in obligate anaerobes Reactions of the Acetyl-CoA Pathway Figure 21.18 Organisms Employing the Acetyl-CoA Pathway Organisms Employing the Acetyl-CoA Pathway 21.10 Methanogenesis Methanogenesis Involves a complex series of biochemical reactions that use novel coenzymes Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Methanofuran) Figure 21.19a Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Methanopterin) Playes a role analogus to THF Resembles folic acid Figure 21.19b Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Coenzyme M) Required for the terminal step of methanogenesis Figure 21.19c Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Coenzyme F430) Contains nickel and required for the terminal step of methanogenesis Figure 21.19d Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Coenzyme F420) A redox coenzyme structurally resembling FMN Oxidized form absorbs light at 420 nm and fluoresces blue-green Figure 21.19e 21.10 Methanogenesis The autofluorescence of coenzyme F420 can be used to identify methanogens microscopically Fluorescence Due to the Methanogenic Coenzyme F420 Autofluourescence in Cells of the Methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri F420 fluorescence in Cells of the Methanogen Methanobacterium formicicum Figure 21.20 Coenzymes of Methanogenesis (Coenzyem B) 7-Mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate Required for the terminal step of methanogenesis catalyzed by the methyl reductase enzyme complex Figure 21.19f 21.10 Methanogenesis H2 is the major electron donor for methanogenesis Methanogenesis from CO2 plus H2 Figure 21.21 21.10 Methanogenesis Additional electron donors exist e.g., formate, CO, organic compounds Methanogenesis from Methanol Figure 21.22a Methanogenesis from Acetate Figure 21.22b 21.10 Methanogenesis Autotrophy in methanogenes occurs via the acetylCoA pathway Energy conservation in methanogenesis is linked to both proton and sodium motive forces Energy Conservation in Methanogenesis Methanophenazine Figure 21.23 21.11 Proton Reduction Pyrococcus furiosus Member of the Archaea Grows optimally at 100°C on sugars and small peptides as electron donors May have the simplest of all anaerobic respiratory mechanisms This organism ferments glucose by reducing protons in an anerobic respiration linked to ATPase activity Modified Glycolysis and Proton Reduction in P. furiosus Fdox/red = ~ -0.42 V 2H+/H2 = ~ -0.42 V Figure 21.24 21.12 Other Electron Acceptors Fe3+, Mn4+, ClO3-, and various organic compounds can serve as electron acceptors for bacteria Fe3+ is abundant in nature and its reduction is a major form of anaerobic respiration Alternative Electron Acceptors for Anaerobic Respirations Figure 21.25 Biomineralization During Arsenate Reduction The reduction of arsenate by sulfate-reducing bacteria has been employed for clean-up of toxic wastes and groundwater After inoculation Synthetic As2S3 Biominerlization of As2S3 after 2 weeks Figure 21.26 21.12 Other Electron Acceptors Halogenated compounds can also serve as electron acceptors via a process called reductive dechlorination (dehalorespiration) Characteristics of Genera of Reductive Dechlorinators 21.13 Anoxic Hydrocarbon Oxidation Aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons (organic compounds containing only carbon and hydrogen) can be oxidized anaerobically Hydrocarbons are oxidized to intermediates that can be catabolized via the citric acid cycle Anoxic Catabolism of the Aliphatic Hydrocarbon Hexane The first step in degradation is the addition of oxygen to the molecule through the incorporation of fumarate Figure 21.27 Anoxic Degradation of Aromatic Hydrocarbon Benzoate Aromatic hydrocarbons are catabolized by ring reduction and cleavage Figure 21.28 Anoxic Oxidation of Methane Methane The simplest hydrocarbon Can be oxidized under anoxic conditions by a consortia containing sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanotrophic archaea Anoxic Methane Oxidation Methane-oxidizing cell aggregates (carriers of reducing power) Possible mechanism of the cooperative degradation of methane Figure 21.29a III. Aerobic Chemoorganotrophic Processes 21.14 Molecular Oxygen as a Reactant in Biochemical Processes 21.15 Aerobic Hydrocarbon Oxidation 21.16 Methylotrophy and Methanotrophy 21.17 Hexose, Pentose, and Polysaccharide Metabolism 21.18 Organic Acid Metabolism 21.19 Lipid Metabolism 21.14 Molecular Oxygen as a Reactant Oxygen plays an important role as a direct reactant in certain biochemical reactions Oxygenases Enzymes that catalyze the incorporation of atoms of oxygen from O2 into organic compounds Two major classes Monooxygenases: incorporate one oxygen atom Dioxygenases: incorporate both oxygen atoms Monooxygenase Activity Hydroxylase Figure 21.30 21.15 Aerobic Hydrocarbon Oxidation Many bacteria and eukaryotic microbes can use aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons as electron donors when growing aerobically Oxygenases are central enzymes in these biochemical reactions Aerobic aromatic compound degradation involves ring oxidation Hydroxylation of Benzene to Catechol by a Monooxygenase Figure 21.31a Cleavage of Catechol by an Intradiol Ring-Cleavage Dioxygenase Figure 21.31b Sequential Reaction of Dioxygenases Figure 21.31c 21.16 Methylotrophy and Methanotrophy Methylotrophs use compounds that lack C-C bonds as electron donors and carbon sources Methanotrophs are methylotrophs that use CH4 The initial step in methanotrophy requires methane monooxygenase (MMO) - Soluble MMO (sMMO) - Membrane-bound MMO (particulate MMO, pMMO) Oxidation of Methane by Methanotrophic Bacteria Methanol dehydrogenase: periplasmic enzyme Figure 21.32 21.16 Methylotrophy and Methanotrophy Methanotrophs are classified into two physiological groups that differ in the pathways invoked for assimilation of carbon into cell material Type I: Ribulose Monophosphate Pathway - Assimilates formaldehyde Type II: Serine Pathway - Assimilates formaldehyde and CO2 Some Characteristics of Methanotrophic Bacteria The Ribulose Monophosphate Pathway Figure 21.34 The Serine Pathway Figure 21.33 21.17 Hexose, Pentose, and Polysaccharide Metabolism Sugars and polysaccharides are common substrates for chemoorganotrophs Polysaccharides such as cellulose and starch are common in nature Their breakdown yields hexoses and pentoses that are readily catabolized by microbes Naturally Occurring Polysaccharides Yielding Sugars 21.17 Hexose, Pentose, and Polysaccharide Metabolism Starch is fairly soluble and readily degraded by many fungi and bacteria employing amylases Hydrolysis of Starch by Bacillus subtilis Purple-black color of the starch-iodine complex Figure 21.37 21.17 Hexose, Pentose, and Polysaccharide Metabolism Cellulose is fairly insoluble and its degradation typically involves attachment of microbes to cellulose fibrils and production of cellulases Cellulose degradation is restricted to relatively few bacteria groups, including the gliding bacteria Sporocytophaga and Cytophaga Cellulose Digestion (Sporocytophaga myxococcoides) Figure 21.35 Cytophaga hutchinsonii Colonies on a Cellulose-Agar Plate Figure 21.36 21.17 Hexose, Pentose, and Polysaccharide Metabolism Pentoses are required for the synthesis of nucleic acids If pentoses are not readily available from the environment, organisms must synthesis themselves The major pathway for pentose production is the pentose phosphate pathway The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Figure 21.39 21.18 Organic Acid Metabolism Organic acids can be metabolized as electron donors and carbon sources by many microbes C4-C6 citric acid cycle intermediates (e.g., citrate, malate, fumarate, and succinate) are common natural plant and fermentation products and can be readily catabolized through the citric acid cycle alone 21.18 Organic Acid Metabolism Catabolism of C2-C3 organic acids typically involves production of oxalacetate through the glyoxylate cycle Glyoxylate cycle - Most TCA cycle reactions + isocitrate lyase & malate synthase The Glyoxylate Cycle Figure 21.40 TCA and Glyoxylate cycles Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. 110 21.19 Lipid Metabolism Lipids are abundant in nature and readily degraded by many microbes Catabolism of fats by microbes is initiated by hydrolysis of the ester bond, yielding fatty acids and glycerol, by extracellular lipases Phospholipases are a class of lipases that attack phospholipids Phospholipase Activity Figure 21.41 Lipases Figure 21.42 21.19 Lipid Metabolism Fatty acids are oxidized by beta-oxidation A series of reactions in which the compounds are first activated by coenzyme A Then two carbons of the fatty acid are successively removed, generating acetyl-CoA Acetyl-CoA is then catabolized through the citric acid cycle Beta-Oxidation Figure 21.43