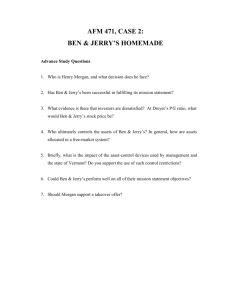

Plummer, William, and Jeff Schnaufer. "A Life On The Ropes

advertisement

Plummer, William, and Jeff Schnaufer. "A Life On The Ropes." People 45.7 (1996): 64. Academic Search Complete. Web. 4 Mar. 2012.A LIFE ON THE ROPES Jerry Quarry fought Ali and Frazier bravely, with no regard for his safety; at 50, he's paying the price AT HOME IN THE HILLS NORTH OF LOS ANGELES, A mother and son are seated for dinner. The son is picking at his food. "If you don't eat the pizza," says the mother reprovingly, "you don't get to drink the Coke." The son looks up, his fingers on a slice. "Hey," he barks, "I'm eating the pizza. Don't give me no lip." Then he extends a hand, playfully punching his mom in the shoulder. At this particular dinner table, though, the hand belongs not to a smart-aleck kid but to a 50-year-old man. It is big and beefy and battered around the knuckles from the glory days when heavyweight fighter Jerry Quarry was the latest Great White Hope. Now his memory of those days is lost in a haze caused by too many punches from the likes of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. The fog that has enveloped Quarry is known as dementia pugilistica, a progressive condition caused by repeated blows to the head resulting in severe brain damage. Quarry has the mentality, says neuropsychologist Dr. Peter Russell, of a person with advanced Alzheimer's disease. "If he lives another 10 years, he'll be lucky," says Russell, who has likened Quarry's dying brain cells to sugar dissolving in water. Quarry has already lost nearly everything. The more than $2 million he made in purses is gone, along with his three wives, two of them the mothers of his three kids. To round out the family tragedy, his younger brothers, and fellow boxers, Mike, 44, and Bobby, 32, are also showing signs of brain damage. Only Jimmy, 51, the oldest brother, is in good health. Until recently, Jerry lived with Jimmy, a loan officer, in Hemet, Calif. Jimmy started the Jerry Quarry Foundation in 1994, purportedly to raise funds for dementia pugilistica. But Jerry's father, Jack, 73, and his sister, Dianna, 49, say the foundation is a ruse--that Jimmy was using Jerry for his own book and movie deals. Jimmy denies the charges. "My dream," says Jimmy, "is to help fighters." That may be, but the family became alarmed last October when Jerry was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame. Quarry sat like a stone among the honorees. When it came time for autographs, he could not sign his name. Three weeks later, Jerry's son Jerry Lyn Quarry, 29, went to Jimmy's house and spirited his father away to live with his mother, Arwanda. She discovered Jerry had been overmedicated. "He was like a zombie," says Arwanda, 69, who, under Dr. Russell's supervision, weaned him from the drugs. "But as Jerry's dad used to say, 'There is no quit in a Quarry.' " Maybe there should have been. Maybe then, Jerry would not be slurring his words, pounding his stomach, and picking absently at his pizza. The Quarrys have boxing in their blood. Jack Quarry weathered the Great Depression by picking cotton during the week and fighting on weekends. "When I was 14, I chopped cotton for $1 a day in Roswell, N. Mex.," says Jack, who was divorced from Arwanda in 1972. "You could go out on Sunday and fight three rounds for $3--that was three days' work!" Like a character out of The Grapes of Wrath, Jack came to California riding a freight car. Soon he and Arwanda were rearing a family in the migrant-labor camps. Jerry was born in Bakersfield in 1945 and first put on boxing gloves at age 3--though nowadays no one in the family wants to take credit for it. Arwanda says her husband took the boys to a gym in L.A. Jack says that Arwanda "wanted me to get the boys out of her hair." One thing is certain: Jack, who had HARD tattooed on his left hand and LUCK on his right, did not abide sissies. The lesson that left the most lasting impression, according to Jimmy, came in a camp in Shafter, Calif., after a softball game. "The umpire called me out on strikes," says Jimmy. "I disagreed. He hit me, and I wouldn't hit him back. My dad saw that. He called me into the bungalow and had my mother put a baby bonnet and a diaper on me, and he made me suck a bottle laying on my bed. I was humiliated." Jerry was impressed too. Jimmy recalls his saying, "I will never let that happen to me." Jack denies the incident ever occurred, but there is no question his boys learned to hit back. "We fought in barrooms to please my father's friends," says Jimmy. "Jerry never wanted to be a fighter. He did it for the attention of my father." Sadly, Jerry can't remember. Asked when he began fighting, he says, "At 12." Mike Quarry, now living in Diamond Bar, Calif., is more lucid than his big brother. A light-heavyweight contender who won 35 fights in a row, he says no one pushed him into the game. He says he became a boxer "because I looked up to Jerry." Back in Jerry's fighting days, that was easy to do. Quarry, as SPORTS ILLUSTRATED noted in 1969, was "a man bred for the ring." He had a 17 1/2-inch neck, muscles like knotted rope, coordination and ferocity. Quarry beat exheavyweight champ Floyd Patterson and in 1973 KO'd contender Earnie Shavers. But he lost his only title shot--to Jimmy Ellis in 1968. Then came Ali and Frazier. Quarry earned his biggest purse, $338,000, against Ali in 1970, and it was after that fight that Jack reportedly told him to quit and buy a gas station. But Ali sliced Jerry up again in 1972. Fighting on the same card, Mike took a terrible beating from light-heavyweight champion Bob Foster. "I told his managers there was something wrong with Michael," says Arwanda, "and that he should get out of boxing. They thought I was just a mother out to protect her child, which I was." Jerry and Mike both kept on fighting. In 1974, Frazier tore Jerry up so badly that Jerry promised to retire, but he came back nine months later to absorb more punishment from Ken Norton. In 1975, Mike was hurt so badly that Jerry--though incapable of recognizing his own plight--begged his brother to quit. But Mike fought five more years. Jerry, too, refused to hang up the gloves, even after a 1983 CAT scan showed signs of dementia. "Unfortunately," says Arwanda, "none of us believed it. Jerry was so normal. He always had a photographic mind. He never wrote down a phone number." It was in 1987 that Arwanda first started to worry as Jerry's short-term memory began to go. But the decisive blow came in 1992, when he was talked into making a comeback in Aurora, Colo. For $1,050, Quarry, 47, was battered for six rounds by a no-name pug who knocked out two of his teeth. "When he came home from the fight in Colorado," says Jimmy, "he couldn't remember the night before." Bobby Quarry, 32, never more than a journeyman fighter and currently in jail in San Luis Obispo, Calif., where he has been charged with receiving stolen property, appears to be in the early stages of dementia. About four years ago, says Arwanda, the California Athletic Commission tested Bobby and deemed him mentally fit but found that he had diminished reflexes in his left arm. A year later, Bobby got kayoed by heavyweight Tommy Morrison. Recently he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, the illness that afflicts Ali. But, insists Arwanda, "none of Bobby's brainpower is gone." Mike's brain still works pretty well, too, despite a fling with cocaine during the '80s. Mike lives in Diamond Bar, Calif., with his wife, Ellen, a marriage and family counselor. By his count, he has had 20 jobs in the last dozen years, ranging from athletic trainer to landscaper. "I've never missed a day," he says. "But I've been subject to forgetting what I was told to do." Mike also loses his balance sometimes, and he occasionally wakes up screaming, punching holes in the wall. Mike admits that he "took too many punches." But then he says, "Life is lived forward, learned backwards." Jerry, meanwhile, is just where he wants to be. He basks in the attention of his mother and sisters. Leaning back in a chair beside the stereo one afternoon, Jerry looks older than his 50 years. Then his sister Brenda Martino thrusts a microphone into his paw, and his blue eyes become electric. Jerry stands up and unleashes a deep rich baritone: "Treat me like a fool/Treat me mean and cruel...." Brenda says she knew that Jerry was out from the spell of the prescription drugs when he began singing again. His mother and sisters--Brenda, 46, manages a grocery, and Dianna a restaurant--tend to Jerry in shifts. They take him on walks and help him carry out the trash. They also help him entertain his kids (Jerry Lyn, Keri, 25, and Jonathan, 9) when they visit and join him in songfests at a social club for Alzheimer's patients. But the news from Dr. Russell is not good. Recent MRI scans indicate that the damage in Jerry's frontal lobe is increasing. Jerry's brain, says Russell, looks like the inside of a grapefruit that has been dropped dozens of times. Occasionally even Jerry seems able to recognize the damage. At one point his mother and sisters tease him about the "girls" flirting with him down at the Alzheimer's club. "I can't have a girlfriend at this given time," Jerry suddenly says. "My situation has been very bad, and you know that." Then the fog rolls in, and he is back in his own world. Until the family moves into the parlor and Brenda hands him the mike and he bursts into song: "Treat me like a fool/Treat me mean and cruel/But love me...." "Jerry was always good to his mom," says Arwanda when he finishes. "Now I'm taking care of him." There is no quit in a Quarry. “Frozen by Parkinson's, Still The Greatest” By TIM DAHLBERG, AP Sports Columnist Associated Press February 19, 2012 04:05 PM Copyright Associated Press. Sunday, February 19, 2012 They gathered in the bowels of the arena where most of the great fights of the last two decades have taken place, old men now all sharing one shining moment from years gone by. They had come to honor The Greatest, though whether Muhammad Ali remembered who they were or knew what it was all about was a matter of speculation that on this night would go unanswered. Some, like Chuck Wepner, couldn't stop talking about the night they won their own personal lottery — a spot across the ring from Ali. Nothing new there, since the Bayonne Bleeder has been talking about it to anyone else who will listen almost every day since. Others, like Leon Spinks, weren't able to talk much at all. "Leon Spinks is here and he needs help," Wepner said. "There are a lot of fighters who need help." This was a night supposed to bring that help, both to fighters like Spinks and those fighting today. Millions would be raised in Ali's name for the Cleveland Clinic's new Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in downtown Las Vegas, where researchers are already busy trying to unlock the puzzles of damage to the human brain. A seat for dinner and the show at the MGM Grand hotel started at $1,500. UFC owner Lorenzo Fertitta spent $1.1 million in an auction for the gloves Ali used against Floyd Patterson in 1965 in the first heavyweight title fight in a city that would become synonymous with boxing. President Barack Obama wished Ali well in a video greeting, and Stevie Wonder was among those on hand to sing birthday wishes to the former heavyweight champion, who turned 70 last month. At the center of it all was an elderly man, mute and his face seemingly frozen as he sat at a table with his wife, Lonnie, and several other family members. Whether boxing caused Ali's Parkinson's is the subject of debate, but it was clear on this night the disease he has fought for three decades has taken a terrible toll on him. He was once a magnificent man with a sculptured body and a mouth that wouldn't stay shut. He's still magnificent in the way that his very presence envelopes and engulfs an arena like it did Saturday night, hushing high-rollers and the elite of this gambling town in a way no other man could — and all without saying a word. They used to trot Joe Louis out like this in his final years, too, a heavyweight great and an American hero reduced to drooling in his wheelchair at ringside. With Ali, though, it seems different in a way if only because you get the feeling that the man who was the ultimate people person still enjoys being around people. "I'm not sad about him, just proud to know him," George Foreman said. "When people ask me if he's the greatest boxer ever, it's an insult. He was the greatest everything, just a great man." Foreman lost the biggest fight of his life to Ali, the stunner in Zaire that cost him the heavyweight title and for a long time derailed his life. He held a grudge for a long time, too, but it's hard to be mad at Muhammad Ali no matter what he did to you in the ring. Ali was back in a makeshift ring on Sunday in the lobby of the MGM, where hundreds of people crowded around to share birthday cake and sing "Happy Birthday" to him. This was a chance for his people — the common people — to get close enough to take a photo and the buzz in the crowd grew as Ali arrived in a golf cart and was helped up a few steps into the ring. The expression on his face never changed as his former business manager, Gene Kilroy, called Ali's family and friends up in the ring to be with him. Moon walker Buzz Aldrin and singer Kris Kristofferson were among the notables, while Spinks and Evander Holyfield also joined him. Lonnie took off his sunglasses and gave him a fork, and everyone watched as Ali concentrated as hard on the task at hand — getting some of the chocolate cake in his mouth — as he ever had fighting Foreman in Africa. A few of his daughters hovered around, and grandbabies were put in his lap. Then, with Holyfield holding him by one arm and his wife by the other, Ali made a slow, trembling, walk around the ring, holding his right arm up waist high to salute the cheers from the crowd. Doctors say not many people survive 30 years of Parkinson's, a debilitating brain disease for which there is no cure. That Ali has lasted this long is, perhaps, a tribute to the great athleticism that served him so well in the ring. Still, the death of his trainer, Angelo Dundee, a few weeks ago and Joe Frazier a few months before that is a reminder that even The Greatest has a limited time on Earth. That seemed to be on the mind of many bunched around the ring in the lobby, holding cell phones aloft in hopes of getting a picture they could show the people back home. The excitement of being so close to Ali was tempered by the reality of how he looked and the difficulty he had trying to get even one bite of frosting in his mouth. Still they cheered his victory lap around the ring, and then watched as Holyfield and others helped him down the few steps toward the golf cart. Before he got in, though, he spotted a little girl in her mother's arms and made a playful little move toward her like he had done thousands of times over to babies throughout his career. As if we needed a reminder that he is indeed The Greatest. Most interesting detail: 1. 1. 1. 1. 2. 2. 2. 2. Connections to Non-Boxers Unique Connections to Family Boxer’s emotions, attitudes, and motivations Society’s attitude toward each exboxer 1. 1. 1. 2. 2. 2. 1. 2. Most interesting detail: