Midterm Review

advertisement

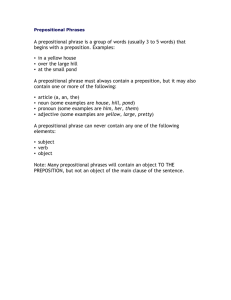

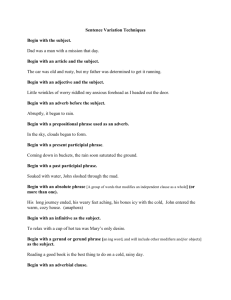

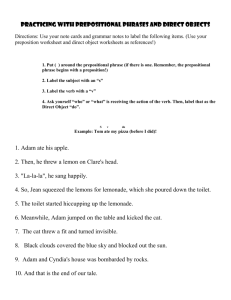

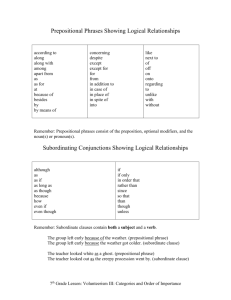

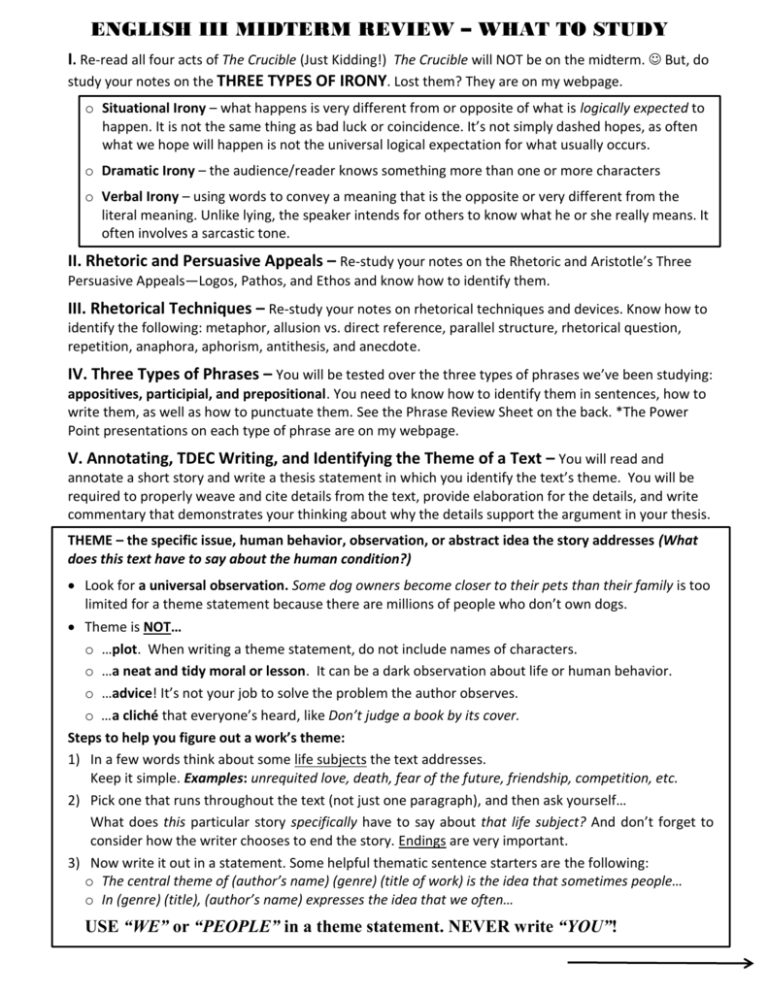

ENGLISH III MIDTERM REVIEW – WHAT TO STUDY I. Re-read all four acts of The Crucible (Just Kidding!) The Crucible will NOT be on the midterm. But, do study your notes on the THREE TYPES OF IRONY. Lost them? They are on my webpage. o Situational Irony – what happens is very different from or opposite of what is logically expected to happen. It is not the same thing as bad luck or coincidence. It’s not simply dashed hopes, as often what we hope will happen is not the universal logical expectation for what usually occurs. o Dramatic Irony – the audience/reader knows something more than one or more characters o Verbal Irony – using words to convey a meaning that is the opposite or very different from the literal meaning. Unlike lying, the speaker intends for others to know what he or she really means. It often involves a sarcastic tone. II. Rhetoric and Persuasive Appeals – Re-study your notes on the Rhetoric and Aristotle’s Three Persuasive Appeals—Logos, Pathos, and Ethos and know how to identify them. III. Rhetorical Techniques – Re-study your notes on rhetorical techniques and devices. Know how to identify the following: metaphor, allusion vs. direct reference, parallel structure, rhetorical question, repetition, anaphora, aphorism, antithesis, and anecdote. IV. Three Types of Phrases – You will be tested over the three types of phrases we’ve been studying: appositives, participial, and prepositional. You need to know how to identify them in sentences, how to write them, as well as how to punctuate them. See the Phrase Review Sheet on the back. *The Power Point presentations on each type of phrase are on my webpage. V. Annotating, TDEC Writing, and Identifying the Theme of a Text – You will read and annotate a short story and write a thesis statement in which you identify the text’s theme. You will be required to properly weave and cite details from the text, provide elaboration for the details, and write commentary that demonstrates your thinking about why the details support the argument in your thesis. THEME – the specific issue, human behavior, observation, or abstract idea the story addresses (What does this text have to say about the human condition?) Look for a universal observation. Some dog owners become closer to their pets than their family is too limited for a theme statement because there are millions of people who don’t own dogs. Theme is NOT… o …plot. When writing a theme statement, do not include names of characters. o …a neat and tidy moral or lesson. It can be a dark observation about life or human behavior. o …advice! It’s not your job to solve the problem the author observes. o …a cliché that everyone’s heard, like Don’t judge a book by its cover. Steps to help you figure out a work’s theme: 1) In a few words think about some life subjects the text addresses. Keep it simple. Examples: unrequited love, death, fear of the future, friendship, competition, etc. 2) Pick one that runs throughout the text (not just one paragraph), and then ask yourself… What does this particular story specifically have to say about that life subject? And don’t forget to consider how the writer chooses to end the story. Endings are very important. 3) Now write it out in a statement. Some helpful thematic sentence starters are the following: o The central theme of (author’s name) (genre) (title of work) is the idea that sometimes people… o In (genre) (title), (author’s name) expresses the idea that we often… USE “WE” or “PEOPLE” in a theme statement. NEVER write “YOU”! Phrases Study Guide the difference between a phrase and a clause A phrase lacks a subject or verb, so it is never a complete sentence; it’s something extra: “smashing into a fence” “the girl with the broken nose” “in the dark of the night” A clause has both a subject and a verb: “I despise dog poop.” I is the subject, and despise is the verb. An independent clause has a subject and a verb and expresses a complete thought: “I despise dog poop.” This is a complete sentence. A dependent clause has a subject and a verb but does not express a complete thought “Because he despises dog poop.” This is a fragment. prepositional phrases - phrases that begin with a preposition and end with a noun or pronoun (the object of the preposition) and acts as an adjective or adverb: “…at the grocery store.” At is the preposition and the grocery store is the object. “…into the box.” Into is the preposition and the box is the object. All the fish, [except Steve], loved to swim. except Steve answers the question which fish? So this prepositional phrase works as an adjective in the sentence. I hid [under the covers] [in terror]. Under the covers is a prepositional phrase working as an adverb, answering the question where? In terror is a prepositional phrase working as an adverb, answering the question how? participial phrases – usually starts with a present or past participle—a verb (usually ending in –ing or –ed) that is acting as an adjective. It is NOT the predicate (the main verb) of the sentence. Example: Helping himself to the buffet, Deshandor loaded up his plate with mac and cheese. (The subject is Deshandor. The predicate is loaded. The underlined participial phrase works as an adjective to describe Deshandor.). Example: Keaton, covered in green slime, hugged his grandmother. (The subject is Keaton. The predicate is hugged. The underlined past participial phrase works as an adjective to describe Keaton.) appositive phrases – a noun phrase that renames/identifies another noun near it. Because an appositive sets up a noun, it often begins with a, an, or the Example: The insect, a large cockroach with hairy legs, is crawling across the kitchen table. Notice how this phrase describes or renames “the insect.” *Also notice that [with hairy legs] is a prepositional phrase within the appositive phrase. An example sentence that contains all three types of phrases: Running [from the gorilla], hoping it would soon tire, Trudy, a renowned tuba player, screamed [into the wind. (participial phrases; [prepositional phrases]; appositive phrases)