Other - New Bulgarian University

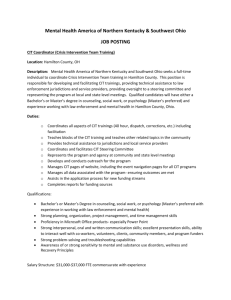

advertisement