3.1 An overview of the use of corpora in applied linguistics

advertisement

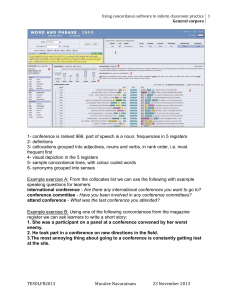

6 Language corpora Liang Maocheng I. overvie w & history An Introduction IV. Methods and Testing Traditional Thoughts of Education Research M ethods Foreign Language Education Language Testing. (Pedagogical) Lexicography V. Learning II. Lg Description Language Descriptions Language Corpora. Stylistics. Discourse Analysis. vs CA Second Language Learning. Individual Differences in Second Language Learning. Social Influences on Language Learning. VI. Teaching III. Cognitive & Social Fashions in Language Teaching Language Acquisition: L1 vs L2 Language, Thought, and Culture. Language and Gender. Language and Politics. Language Teacher Education. World Englishes. The Practice of LSP Bilingual Education. M ethodology. Computer Assisted Language Learning Fig. 0 A Bird’s-Eye-Vie w of Applied Linguistic Studies 7.1 Introduction • • • • • • • • • 7.1 Introduction 7.2 Empiricism, corpus linguistics, and electronic corpora 7.3 Applications of corpora in applied linguistics 7.3.1 An overview of the use of corpora in applied linguistics 7.3.2 The Lexical Syllabus: a corpus-based approach to syllabus designing 7.3.3 Data-Driven Learning (DDL) 7.3.4 Corpora in language testing 7.3.5 Corpus-based interlanguage analysis 7.4 Future trends 7.1 Introduction • The debates about whether corpus linguistics should be defined as a new discipline, a theory or a methodology. • Some linguists working with corpora tend to think that corpus linguistics goes well beyond the purely methodological role by re-uniting the activities of data gathering and theorizing, thus leading to a qualitative change in our understanding of language (Halliday, 1993:24), • More researchers (e.g., Botley & McEnery, 2000; Leech, 1992; McEnery & Wilson, 2001: 2; Meyer, 2002:28; ) seem to share the view that corpus linguistics is a methodology contributing to many hyphenated disciplines in linguistics. This methodological nature has brought about the convergence of corpus linguistics with many disciplines, of which applied linguistics probably enjoys the most benefits corpus linguistics can offer. 2. Empiricism, corpus linguistics, and electronic corpora • The 1950s witnessed the peak of empiricism in linguistics, with Behaviorists dominating American linguistics, and Firth, a leading figure of British linguistics at the time, forcefully advocating his data-based approach with his well-cited belief that “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” (Firth, 1957). • However, with the quick advent of generative linguistics in the late 1950s, empiricism gave way to Chomskyans, whose approach is based on the intuition of ‘ideal speakers’ rather than collected performance data. It was not until the 1990s that there was again a resurgence of interest in the empiricist approach (Church & Mercer, 1993). • Corpus linguistics is empirical. Its object is real language data (Biber et al., 1998; Teubert 2005). In fact, there is nothing new about working with real language data. In as early as the 1960s, when generative linguistics was at its peak, Francis and Kucera created their one-million-word corpus of American written English at Brown University (Francis and Kucera, 1982). • Then, in the 1970s, Johansson and Leech at the University of Oslo and the University of Lancaster compiled the LancasterOslo/Bergen Corpus (LOB), the British counterpart of the American Brown Corpus. • Since then, there has been a boom of corpus compilation. Spoken corpora (such as the London-Lund Corpus, see Svartvik, 1990) and written corpora, diachronic corpora (such as ICAME) and synchronic corpora, large general corpora (such as the BNC and the Bank of English) and specialized corpora, native speakers’ language corpora and learner corpora and many other types of corpora were created one after another. • These English corpora are constantly providing data to meet the various needs of applied linguistics. • After a few decades of world-wide corpusrelated work, several tendencies now seem to be obvious in corpus building in the new empiricist age. • First, modern corpora are becoming ever larger and more balanced, and therefore often claimed to be more representative of the language concerned. • Second, there is often the need for rationalism and empiricism to work together. • Third, many types of specialized language corpora are being built to serve specific purposes. • Fourth, many researchers in applied linguistics have realized the usefulness of corpora for the analysis of learner language. • Finally, as corpus annotation is believed to bring “added value” (Leech, 2005) to a corpus, there is a tendency that corpus annotations are becoming more refined, providing detailed information about lexical, phraseological, phonetic, prosodic, syntactic, semantic, and discourse aspects of language. 7.3 Applications of corpora in applied linguistics • 7.3.1 An overview of the use of corpora in applied linguistics • 7.3.2 The Lexical Syllabus: a corpus-based approach to syllabus designing • 7.3.3 Data-Driven Learning (DDL) • 7.3.4 Corpora in language testing • 7.3.5 Corpus-based interlanguage analysis • In order to provide an overall picture of the extensive use of corpora in applied linguistics, this section will first present an overview of the use of corpora in applied linguistics. • Following the overview, our discussion will focus on a few major areas of applied linguistics where corpora are playing increasingly important roles, namely, syllabus design, data-driven learning, language testing, and interlanguage analysis. 3.1 An overview of the use of corpora in applied linguistics • Leech (1997) summarizes the applications of corpora in language teaching with three concentric circles. Direct use of corpora in teaching Use of corpora indirectly applied to teaching Further teaching-oriented corpus development Figure 1: The use of corpora in language teaching (from Leech, 1997) • Drawing on Fligelstone (1993), Leech (1997) claims that ‘the direct use of corpora in teaching’ (the innermost circle) involves teaching about [corpora], teaching to exploit [corpora], and exploiting [corpora] to teach. According to Leech (1997), teaching about corpora refers to the courses in corpus linguistics itself; teaching to exploit corpora refers to the courses which teach students to exploit corpora with concordance programs, and learn to use the target language from real-language data (hence data-driven learning, to be discussed in more detail later in this section). Finally, exploiting corpora to teach means making selective use of corpora in the teaching of language or linguistic courses which would traditionally be taught with non-corpus methods. • The more peripheral circle, ‘the use of corpora indirectly applied to teaching’, according to Leech (1997), involves the use of corpora for reference publishing, materials development, and language testing. In reference building, the Collins (now HarperCollins), Longman, Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press and many other publishers have been actively involved in the publication of corpus-based dictionaries, electronic corpora, and other language reference resources, especially those in the electronic form. • As Hunston states, “corpora have so revolutionised the writing of dictionaries and grammar books for language learners that it is by now virtually unheard-of for a large publishing company to produce a learner’s dictionary or grammar reference book that does not claim to be based on a corpus” (Hunston, 2002:96) (For more detailed accounts of the use of corpora in dictionary writing, see Sinclair, 1987; Summers, 1996). In materials development, increasing attention is paid to the use of corpora in the compilation of syllabuses (to be discussed later in this section) and other teaching materials. Also in the second of the three concentric circles is language testing (See Section 3.4 for more detail), which “benefits from the conjunction of computers and corpora in offering an automated, learner-centred, open-ended and tailored confrontation with the wealth and variety of real-language data”. • Finally, the outermost circle, ‘further teaching-oriented corpus development’, involves the creation of specialized corpora for specific pedagogical purposes. To illustrate the need to build such specialized corpora, Leech (1997) mentions LSP (Language for Specific Purposes) corpora, L1 and L2 developmental corpora (also an important data source for Second Language Acquisition research), and bilingual/ multilingual corpora. Leech (1997) believes these are important resources that language teaching can benefit from. • Of course, Leech’s (1997) discussion focuses on the applications of corpora in language teaching. Second Language Acquisition research, one of our major concerns in this book, is not as important for him. In fact, corpus-based approaches to SLA studies, particularly to interlanguage analysis, have become one of the most prevalent research methodologies for the analysis of learner language. This issue will be brought to a more detailed discussion later in the chapter. 3.2 The Lexical Syllabus: a corpusbased approach to syllabus designing • The notion of a ‘lexical syllabus’ was originally proposed by Sinclair and Renouf (1988), and further developed by Willis (1990), who points out a contradiction between syllabus and methodology in language teaching: • The process of syllabus design involves itemising language to identify what is to be learned. Communicative methodology involves exposure to natural language use to enable learners to apply their innate faculties to recreate language systems. There is an obvious contradiction between the two. An approach which itemises language seems to imply that items can be learned discretely, and that the language can be built up from an accretion of these items. Communicative methodology is holistic in that it relies on the ability of learners to abstract from the language to which they are exposed, in order to recreate a picture of the target language. (Willis, 1990: viii) • The lexical syllabus attempts to reconcile the contradiction. Rather than relying on a clear distinction between grammar and lexis, the lexical syllabus blurs the distinction and builds itself on the notion of phraseology. • As early as a few decades ago, some researchers (e.g., Nattinger and DeCarrico, 1989; 1992; Pawley & Syder, 1983) came to realize that phrases (also called ‘lexical phrases’, ‘lexical bundles’, ‘lexical chunks’, ‘formulae’, ‘formulaic language’, ‘prefabricated routines’, etc.) are frequently used and are therefore important for the teaching and learning of English. • Later researchers such as Cowie (1998), Skehen (1998) and Wray (2002) are also convinced that a better command of such phrases can improve the fluency, accuracy and complexity of second language production. • Unfortunately, most syllabuses for ELT are based on traditional descriptive systems of English, which consist of grammar and lexis (Hunston, 2002). Such descriptive systems, according to Sinclair (1991), fail to give a satisfactory account of how language is used. • Besides, combining the building blocks (lexis) with grammar does not result in a good account of the phrases in a language. • Against this background, Sinclair (1991) proposes a new descriptive system of language, completely denying the distinction between grammar and lexis and putting phraseology at the heart of language description. • The lexical syllabus is not a syllabus consisting of vocabulary items. It comprises phraseology, which “encompasses all aspects of preferred sequencing as well as the occurrence of so-called ‘fixed’ phrases” (Hunston, 2002:138). • Such a syllabus, according to Hunston (2002), differs from a conventional syllabus only in that the central concept of organization is lexis. To put it simply, as a relatively small number of words in English account for a very high proportion of English text, it makes sense to teach learners the most frequent words in the target language. • However, as learning words out of their context does not seem to be a good idea, a syllabus had better not be designed in such a way that it only specifies the vocabulary items to be learned. Rather than the lexis of the target language, phraseology (words with their most frequently used patterns) is what is to be specified in detail in a lexical syllabus. • According to Sinclair & Renouf (1988), ‘the main focus of study should be on • (a) the commonest word forms in the language; • (b) the central patterns of usage; • (c) the combinations they usually form’ (1988:148). • This is exactly what is covered in Willis’ (1990) syllabus. • Willis (1990) argues that the lexical syllabus effectively addresses “the main focus of study” mentioned in Sinclair & Renouf (1988): (a) Willis’ (1990) syllabus consists of three different levels. • Level I covers the most frequent 700 words in English, which, according to Willis (1990), make up around 70% of all English text. • Level II covers the most frequent 1,500 and • Level III covers the most frequent 2,500 words in English. • (b) The lexical syllabus illustrates the central patterns of usage of the most frequent words in English. Such patterns of usage were later developed into a system of grammar called “pattern grammar” (Hunston & Francis, 2000). • (c) Typical combinations of word forms (collocations) from authentic language are highlighted to provide information about the phraseology of the words concerned. • It can be seen that the lexical syllabus is not a syllabus which lists all the vocabulary items learners are required to learn. • To Willis (1990), “English is a lexical language”, meaning that “many of the concepts we traditionally think of as belonging to ‘grammar’ can be better handled as aspects of vocabulary” (Hunston, 2002:190). Conditionals, for example, could be handled by looking at the hypothetical meaning of the word ‘would’. • The most productive way to interpret grammar, therefore, is as lexical patterning, rather than as rules about the sequence of words that often do not work. • However, the lexical syllabus, as proposed in Willis (1990), is not without challenges. • First, frequency is a useful factor to take into consideration when a syllabus is designed. However, language learning is not that simple. Native language influence, cultural difference, learnability, usefulness, and many other factors can all bring about some difficulty for language learning. • As Cook (1998:62) notes, “an item may be frequent but limited in range, or infrequent but useful in a wide range of contexts”. Proponents of the Lexical Syllabus seem to have ignored this fact. They believe their syllabus will work for learners of all linguistic and ethnic backgrounds. To many researchers and practitioners of applied linguistics, such a belief is too simplistic to account for complicated processes such as language learning. • Second, it is not an easy task to select a manageable yet meaningful number of items from the entire vocabulary of a language for inclusion in a lexical syllabus. • While it may be true that the 2,500 words in Willis’ syllabus can account for 80% of all English text, knowing 80% of the words in a text does not guarantee good comprehension. In fact, most of the 80% are functional words or delexicalized words, which do not have much content. In other words, the role of the commonest words in language comprehension and production may not be as significant as the high frequency counts suggest. Also, while it may be relatively easy to include a content word as an entry in a lexical syllabus, functional words can be a big problem. Such a word entry may take tens of pages long in the lexical syllabus. If the most frequent words are to be accounted in detail, it is very likely that the syllabus will become a comprehensive guide to the usage of functional words. • Finally, the size of the syllabus may also be a problem. Willis (1990), when creating his “elementary syllabus”, had to work with huge amounts of data. He complained that “The data sheets for Level I alone ran to hundreds of pages which we had to distil into fifteen units” (Willis, 1990:130). • We just cannot help wondering how many thousands of data sheets would have to be created if a syllabus had to be written for advanced learners. 3.3 Data-Driven Learning (DDL) • The use of corpora in the language teaching classroom owes much to Tim Johns (Leech, 1997), who began to make use of concordancers in the language classroom in as early as the 1980s. He then wrote a concordance program himself, and later developed the concept of Data-Driven Learning (DDL) (See Johns, 1991). • DDL is an approach to language learning by which the learner gains insights into the language that she is learning by using concordance programs to locate authentic examples of language in use. The use of authentic linguistic examples is claimed to better help those learning English as a second or foreign language than invented or artificial examples (Johns, 1994). • These authentic examples are believed to be far better than the examples the teachers make up themselves, which unavoidably lack authenticity. In DDL, the learning process is no longer based solely on what the teacher expects the learners to learn, but on the learners’ own discovery of rules, principles and patterns of usage in the foreign language. • Drawing from George Clemenceau’s (1841-1929) claim that ‘War is much too serious a thing to be left to the military’ (quoted in Leech, 1997), Johns believes that ‘research is too serious to be left to the researchers’ (Johns, 1991:2), and that research is a natural extension of learning. • The theory behind DDL is that students could act as ‘language detectives’ (Johns, 1997:101), exploring a wealth of authentic language data and discovering facts about the language they are learning. • In other words, learning is motivated by active involvement and driven by authentic language data, whereas learners become active explorers rather than passive recipients. To a great extent, this is very much like researchers working in the scientific laboratory, and the advantage lies in the direct confrontation with data (Leech, 1997). • Murison-Bowie, the author of the MicroConcord Manual, gives some very persuasive reasons for using a concordancer: • … any search using a concordancer is given a clearer focus if one starts out with a problem in mind, and some, however provisional, answer to it. You may decide that your answer was basically right, and that none of the exceptions is interesting enough to warrant a re-formulation of your answer. On the other hand, you may decide to tag on a bit to the answer, or abandon the answer completely and to take a closer look. Whichever you decide, it will frequently be the case that you will want to formulate another question, which will start you off down a winding road to who knows where. (Murison-Bowie, 1993:46, cited in Rezeau, 2001:153) • It can be seen that in DDL, language learning is a hypothesistesting process, in which whenever the learner has a question, she goes to the concordancer for help. If what she discovers coincides with the authentic language data shown in the concordance lines, her hypothesis is tested to be true, and her knowledge of the language is reinforced; conversely, if the concordance data contradict her hypothesis, she modifies it and comes closer to how the language should be used. • Higgins (1991) mentions that classroom concordancing tends to have two characteristic objectives: • “using searches for function words as a way of helping learners discover grammatical rules, and • searching for pairs of near synonyms in order to give learners some of the evidence needed for distinguishing their use” (p.92). • What the foregoing example shows is that in data-driven learning, the learner often has a question in mind. She then goes to explore the data for an answer. The whole process, as mentioned before, involves testing a hypothesis with hands-on activities. In so doing, the learner is more likely to be motivated. • It is worth mentioning that many of the features of DDL fit exactly into the constructivist approach to language teaching, in which: 1. Learners are more likely to be motivated and actively involved; 2. The process is learner-centered; 3. Learning is experimentation; 4. Hands-on activities and experiential learning; 5. Teachers work as facilitators; • As pointed by Gavioli (2005:29), DDL raised several pedagogic questions, which we have to answer when we encourage our students to engage themselves in data-driven learning: 1. if learners are to behave as data analysts, what should be the role of the teacher? 2. the work of language learners is similar to that of language researchers insofar as “effective language learning is itself a form of linguistic research” (Johns 1991:2). So, should we ask the learners to perform linguistic research exactly like researchers? 3. provided that learners adopt the appropriate instruments and methodology to actually be able to perform language research, are the results worth the effort? • And, to this I would like to add Barnett’s (1993) note: 4. “the use of computer applications in the classroom can easily fall into the trap of leaving learners too much alone, overwhelmed by information and resources”. • What can we do to improve this situation in data-driven learning? 3.4 Corpora in language testing • It is only recently that language corpora have begun to be used for language testing purposes (Hunston, 2002), though language testing could potentially benefit from the conjunction of computers and corpora in offering an “automated, learner-centred, open-ended and tailored confrontation with the wealth and variety of real-language data” (Leech, 1997). • In fact, the use of corpora in language testing is such a new field of studies that Leech (1997) only mentions the advantages of corpus-based language testing, and predicts that “automatic scoring in terms of ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ responses is feasible”. • Hunston (2002:205) also states that the work reported in her book is “mostly in its early stages”. • Alderson (1996), in a paper entitled “Do corpora have a role in language assessment?”, has to claim that he could only “concentrate on exploring future possibilities for the application of computer-based language corpora in language assessment” (Alderson, 1996:248). • To the best of my knowledge, the use of corpora in language testing roughly falls into two categories. One is the use of corpora and corpus-related techniques in the automated evaluation of test questions (particularly subjective questions like essay questions or short-response questions), and • the other is the use of corpora to make up test questions (mostly objective questions). • The reason behind this is simple: making up subjective questions does not take a lot of efforts but evaluating them does; similarly, evaluating objective questions does not take a lot of efforts but making up these questions may take a lot of time. • The earliest attempt to automate essay scoring was made several decades ago, when Ellis Page and his collaborators devised a system called PEG (Project Essay Grade) to assign scores for essays written by students (Page, 1968). • From a collection of human-rated essays, Page extracted 28 text features (such as the number of word types, the number of word tokens, average word length, etc.) that correlate with human-assigned essay scores. • He then conducted a multiple regression, with human-assigned essay scores as the dependent variable and the extracted text features as independent variables. • The multiple regression yielded an estimated equation, which was then used to predict the scores for new essays. • Following Page’s methodology, ETS produced another automated essay scoring system called the E-rater, which has been used to score millions of essays written in the GMAT, GRE and TOEFL tests (Burstein, 2003). • Liang (2005) also made an exploratory study, in which he extracted 13 essay features to predict scores for new essays. • All the above-mentioned studies involved the use of corpora and corpus-related techniques. They reported good correlations between human-assigned essay scores and computer-assigned essay scores. • For more information about automated essay scoring, see Shermis & Burstein (2003). • The direct use of corpora in the automatic generation of exercises (or test questions) is also a relatively new field of study. To the best of my knowledge, two studies have been reported in the literature. • Wojnowska (2002) reported a corpus-based test-maker called TestBuilder. The Windows-based system extracts information from a tagged corpus. It can help teachers prepare two types of single-sentence test items --- gapfilling (cloze) and hangman. While the system may be useful for English teachers, the fact that the questions generated with the system can only be saved in the pure text format greatly reduces its practicality. • In other words, the test generated allows no interaction with the test-taker, and the teacher or the test-taker herself has to judge the test performance and calculate the scores manually. Besides, gapfilling and hangman are very similar types of exercises, both involving the test-taker filling gaps with letters or combinations of letters (words). • Obviously, this system has not made full use of the capacity of the computer and the corpora. Wilson (1997) reported her study on the automatic generation of CALL exercises from corpora. Unfortunately, the study has not resulted in a computer program, and the exercises generated are not interactive either. • To take better advantage of corpora for language testing purposes, we started a project of our own. • From this study a Windows-based program (called CoolTomatoes) has derived, which is capable of automatically generating interactive test questions or exercises from any user-defined corpus. • CoolTomatoes has a number of useful features. • Questions are based on real language data. As the corpus comprises real language data, the test questions generated by CoolTomatoes are naturally more meaningful. These questions are more likely to test and enhance test-takers’ ability to use real language to fulfill real-life tasks. • Question generation is fully customizable. Both the corpus and the answer options can be customized. The user can choose to add a new text to an existing corpus, or choose to load different corpora. This is important because test questions need to be at different difficulty levels for different students, and the difficulty of the test questions is determined by the difficulty of the corpus text. Customizing the answer options is also important because every teacher/tester almost always wants to have their own questions (sometimes for their own students) in the test. • Interaction with the test-maker. To eliminate chances of highly similar questions or poor questions due to an inappropriate corpus, CoolTomatoes allows the user to preview the questions to be generated. If necessary, the user can further edit, delete, and add questions. • Dual output if needed: The user can choose to generate a print-out test (for the traditional class) or an interactive test to be done on a stand-alone computer or on the web. • Real-time feedback for the test-takers: In an interactive test generated by CoolTomatoes, testtakers are given real-time feedback about: 1) whether a question has been correctly answered; 2) the overall performance of the test-taker (Figure 3). • Automatic submission of test performance: If a webserver and an email address are defined, all testtakers’ test performance data can be automatically submitted to the email address whereby learning can be monitored. • Suggestions • While the high customizability of CoolTomatoes brings considerable convenience to the language teacher/tester and makes learning and testing more of a fun, a few cautions have to be taken before a test can be released to the end-user learner. • First, the difficulty of the corpus on which to base the test questions has to be carefully monitored. It is, needless to say, never rewarding to test your students against something that is far beyond their ability or too easy to be worthwhile. • Second, the answer options have to be carefully chosen. If an achievement test is to be made, for example, the answer options need to include the syntactic and/or lexical focuses the learners have just been exposed to. If a proficiency test is to be made, several trials may be necessary to determine what is going to be in the test. It may be a good idea to generate a large number of test questions and manually filter out the less appropriate ones. • Third, for reasons of content-related language, it is always necessary to know what is in a test before you ask your students to do it. • Finally, there is the danger of overwork on the part of the students. Learners’ motivation to learn and to be tested should be cautiously preserved and encouraged. It is never a good idea to drown them with tons of automatically generated exercises. • As seen from our study reported in this section, the advantages for corpus-based language testing are obvious. As a corpus comprises collections of real-life language data, corpus-based language tests or exercises are unmistakably genuine real-life samples. In the modern age when authenticity of language use is greatly emphasized in language testing, corpus-based approaches certainly enjoy prosperous future. • The second advantage is that corpus-based language tests can be automatically graded, since the questions are retrieved from corpora, and the right answers to these questions are always readily extractable. Of course, with the questions and the answers in the corpus, interactive test questions could be devised. • One more advantage for corpus-based language tests is speed. The computer can work faster than the best human assessor if it is told exactly what to do. • Of course, a lot more remains to be explored in how language corpora can be appropriately used in language testing, and whether subjective test items such as essay questions can be automatically generated and graded. • Besides, before the reliability and validity of these automatically generated test questions are verified, it is questionable whether such questions are suitable for highstakes tests. 3.5 Corpus-based interlanguage analysis • While Svartvik (1996), perhaps not without hesitation, predicts that “corpus is becoming mainstream”, Thomas & Short (1996), without any hesitation, contend that “corpus has become mainstream”. • More encouragingly, Čermák (2003) says that “it seems obvious now that the highest and justified expectations in linguistics are closely tied to corpus linguistics”, and that “it is hard to see a linguistic discipline not being able to profit from a corpus one way or another, both written and oral”. • Teubert (2005) concludes that “Today, the corpus is considered the default resource for almost anyone working in linguistics. No introspection can claim credence without verification through real language data. Corpus research has become a key element of almost all language study.” • Research on interlanguage is no exception. As researchers in many linguistic disciplines are enjoying the profits corpus linguistics constantly brings, SLA researchers also come to realize that most of the methodologies (perhaps also some important notions about what language is) in corpus linguistics also have important light to shed on interlanguage analysis. • Needless to say, corpus-based interlanguage analysis requires interlanguage corpora (or learner corpora) to be collected. This is a relatively recent endeavor: it was not until the late 1980s and early 1990s that academics and publishers started collecting learner corpora (Granger, 2002), and corpus-based research on interlanguage began to be published when Granger and her collaborators edited their collection of papers in a volume called Learner English on Computer (Granger, 1998). • Not surprisingly, Granger’s efforts have been followed by many SLA researchers the world over, and the learner corpus has become “the default resource” for almost anyone involved in interlanguage analysis. • According to Granger (2002), corpus-based interlanguage analysis usually involves one of the two methodological approaches: • Computer-aided Error Analysis (CEA) and • Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA). • Computer-aided Error Analysis • Computer-aided Error Analysis (CEA) evolved from Error Analysis (EA), which was a widespread methodology for interlanguage analysis in the 1970s. • EA has been criticized for several weaknesses: • EA is based on heterogeneous data and therefore often impossible to replicate; • EA often suffers from fuzzy error categories; • EA cannot cater for avoidance; • EA only deals with what learners cannot do; • EA cannot provide a dynamic picture of L2 learning. • According to Dagneaux et al. (1999), these weaknesses of EA highlight the need for a new direction in EA analysis. Granger (2002:13) forcefully contends that CEA is a great improvement on EA in that the new approach is computer-aided, involves a high degree of standardization, and renders it possible to study errors in their context, along with nonerroneous forms. • The first way to conduct a computer-aided error analysis is to search the learner corpus for error-prone linguistic items using a concordancer. The advantage is that it is very fast and errors can be viewed in their context. However, phenomena such as avoidance and non-use remain a problem. • The second way to conduct a computer-aided error analysis is more common and powerful. This method requires a standardized error typology to be developed beforehand. • This typology is then converted to an error-tagging scheme, with conventions about what label is to be used to flag each error type in the learner corpus. Then, experts or native speakers are employed to read the data carefully, and label each error in the corpus with its corresponding tag in the error-tagging scheme. This process is very time-consuming, but the efforts are rewarding. Once the tagging is complete, concordancers can be used to search the corpus for each type of errors. The advantages for this method are also obvious: error categorization is standardized; all errors are counted and viewed in their context. • Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis • Contrastive Interlanguage Analysis (CIA) involves comparing a learner corpus with another corpus or other corpora. Very often, the purpose of such comparison is to shed light on features of non-nativeness in learner language. • Such features can be learner errors, but more often, they are instances of overpresentation and underpresentation (Granger, 2002). That is to say, by means of comparison, CIA expects to find out which linguistic items in learner language are misused, overused or underused. Besides, CIA also attempts to discover the reasons for such deviations. • According to Granger (1998; 2002), CIA involves two types of comparison: NS/NNS comparisons and NNS/NNS comparisons. NS/NNS comparisons are intended to reveal non-native features in learner language. The assumption behind such comparisons, as can be figured out, is that native speakers’ language can be regarded as a norm, to which the learners are expected to come closer in the process of language learning. The purpose of NNS/NNS comparisons is somewhat different. Granger maintains that comparisons of learner data from different L1 backgrounds may indicate whether features in learner language are developmental (characteristic of all learners at a certain stage of their language learning) or L1induced. • In addition, Granger believes that bilingual corpora containing learners’ L1 and the target language may also provide evidence for possible L1 transfer. It is worth mentioning that whichever comparison applies, a statistical test is often necessary to reveal whether the difference found is statistically significant. This methodology is drawing some criticism. Some linguists insist that any variety of a language has its own right to be a variety. • The CIA methodology has yielded abundant research findings. Most remarkably, Granger and her collaborators published dozens of research articles, most of which are included in Granger (1998) and Granger et al. (2002). Besides, the empiricist methodology in the new era has also aroused the interest of SLA researchers the world over, who have been enthusiastically involved in the creation of new learner corpora and corpus-based interlanguage studies, with the result that an ever-growing number of such studies are published in renowned international journals. • In China, after the publishing of CLEC, two more learner corpora, namely, COLSEC (Yang & Wei, 2005), and SWECCL (Wen et al., 2005) have been released, providing data for corpus-based interlanguage studies in the Chinese context. It is particularly worth noting that SWECCL has two components, SECCL (Spoken English Corpus of Chinese Learners) and WECCL (Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners), with a total of about 1 million words each. • Undoubtedly, CIA is an effective methodology to reveal non-native features in learner language. However, how to interpret non-native features in learner language seems to be a more complicated matter, which cannot be simply attributed to L1 induction or developmental patterning. • Factors such as input may also come into play. It may be necessary to isolate sources of observed effects (cf. Juffs, 2001). For example, Tono (2004) did an interesting study, in which she used a multifactorial analysis to separate L1-induced variation from L2-induced variation and learner input variation. • Just as Cobb (2003) claims, learner corpus research ‘‘amounts to a new paradigm, and a great deal of methodological pioneering remains to be done’’. 4. Future trends • Several trends now seem obvious in the use of language corpora in applied linguistics: 1. With the growth of the power of computer hardware and software and the increasing availability of more texts, the sizes of general corpora may grow to billions of words. While such large general corpora may still be necessary for our understanding of language, several types of specialized corpora may be necessary in applied linguistics. • For language learning and language teaching purposes, large is not always beautiful. It is the usefulness of corpora that really matters. After all, too much may not be better than enough. For a pedagogic corpus, size and representativeness are not as important as they are for a general corpus. Neologisms, for example, may be interesting to researchers, but they may not always be what we would like learners to learn. It is very likely that corpora for learners to explore will be carefully controlled in terms of the typicality and difficulty of the language therein. This will probably also be the corpus on which to base language testing, though not necessarily for syllabus designing. • For interlanguage researchers, representativeness of data will always be an important consideration. However, for different research purposes, what is going to be represented may also be radically different. Therefore, various types of specialized corpora may be necessary. Researchers may have to build their own corpora to meet their specific needs. In corpusbased interlanguage analysis, native speaker norms will not be put to death in at least a few decades’ time. 2. Corpus-based methods will have to be supplemented with other methods (such as experimentation) if their findings are to become more meaningful and convincing. Corpus linguistics is virtually exclusively based on frequency (Gries, to appear). “The assumption underlying basically all corpusbased analyses”, according to Gries, “is that formal differences correspond to functional differences such that different frequencies of (co-)occurrences of formal elements are supposed to reflect functional regularities” (ibid: 5). • The problem lies in that corpus methods exclusively rely on searchable formal elements. The result is that it can be difficult, if not altogether impossible, to infer the cognitive process going on in the learners’ mind on the basis of what can be found in text. In other words, corpus linguistics works on the product. It does not help much when our interest is in the process. Whenever necessary, other methodologies may have to be assorted to as supplements. 3. With Construction Grammar of Cognitive Linguistics becoming more widely accepted, interest in the role of phraseology will keep growing. The idiom principle, which states that “a language user has available to him or her a large number of semi-preconstructed phrases that constitute single choices, even though they might appear to be analyzable into segments” (Sinclair 1991:110), will have an increasing effect on language teaching, interlanguage analysis, and language research in general. 4. Interlanguage analysis will focus more of its attention on speech, and on syntactic aspects of learner language. These aspects of interlanguage have by far not been adequately explored. Besides, longitudinal studies may be especially rewarding. Just as Cobb (2003:403) claims, it is “characteristic of learner corpus methodology to extrapolate from crosssectional to longitudinal data” in order to address developmental issues with respect to learner interlanguage. Such data types are more likely to “accurately elucidate developmental pathways”. • Whether taken as a new discipline, a new theory, or a new methodology, corpus linguistics is exerting influence on an ever-growing number of people in applied linguistics. These people might virtually be anyone in the applied linguistics circles, from the syllabus designer to the materials writer, from the language publisher to the dictionary user, from the teacher to the learner, from the test maker to the test-taker, and from the researcher to the researched. • No matter how language corpora are used in applied linguistics, for whatever purposes, the central theme of corpus linguistics remains the same: what is more frequent is also more important. • References (omitted) • The chapter is based on Liang Maocheng’s Chapter in Wu Yi’an’s book (forthcoming). Thank You!