business cycle

advertisement

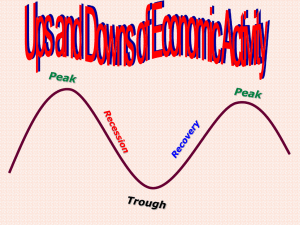

Calling it a Recession Ka-fu Wong School of Economics and Finance University of Hong Kong ** Prepared for the Professional Development Seminar for Economics Teachers, October 21, 2009. 1 Outline Definition of business cycles Why do we care about business cycles Causes of business cycles Business cycles dating NBER, e.g., US Shiskin Rule, e.g., HK Hong Kong’s dependence on US Causes of the recent financial crisis and recession 2 Definition of Business Cycles A cycle consists of expansions occurring at about the same time in many economic activities, followed by similarly general recessions, contractions, and revivals which merge into the expansion phase of the next cycle; this sequence of changes is recurrent but not periodic; in duration business cycles vary from more than one year to ten or twelve years; they are not divisible into shorter cycles of similar character with amplitudes approximating their own. (Burns and Mitchell, 1946, p.3) Burns, A.F., and W. C. Mitchell (1946), Measuring Business Cycles. New York: NBER. 3 Definition of Business Cycles The term business cycle (or economic cycle) refers to economy-wide fluctuations in production or economic activity over several months or years. Expansion (or boom) episode: from local minimum output to maximum output, i.e., from trough to peak Contraction (recession) episode: from local maximum output to minimum output, i.e., from peak to trough 4 100 95 90 Output Level 105 110 Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 5 Definition of Business Cycles 100 95 90 Output Level 105 110 R 0 50 100 Time 150 200 6 100 105 110 output level 115 120 What if … 0 50 100 Time 150 200 7 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles Deviations of output from trend Also known as growth cycles or deviation cycles. Expansion (or boom) episode: output grows at a higher rate than the trend. Contraction (recession) episode: output grows at a lower rate than the trend. 8 115 110 105 100 95 output level 120 125 130 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 9 0 -5 -10 output level 5 10 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 10 0 -5 -10 output level 5 10 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 11 115 110 105 100 95 output level 120 125 130 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 12 110 105 100 output level 115 120 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 13 110 105 100 output level 115 120 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles 0 50 100 Time 150 200 14 Alternative Definition of Business Cycles Difficulty: We need to define and estimate the trend before we can conclude about the business cycles Trends: Linear trend Quadratic trend Stochastic trend Filtering out the high-frequency fluctuations and the low-frequency fluctuations using some advanced statistical technique, known as Band Pass Filter. 15 US Industrial production index, levels Stock and Watson (1998, Fig. 1.1) 16 Estimate of the cyclical component of US industrial production index Stock and Watson (1998, Fig. 1.2) ** A bandpass filter was used to isolates fluctuations at business cycle periodicities, six quarters to eight years. 17 Macroeconomics is about business cycles The explanation of fluctuations in aggregate economic activity is one of the primary concerns of macroeconomics. The most commonly used framework for explaining such fluctuations is Keynesian economics. In the Keynesian view, business cycles reflect the possibility that the economy may reach short-run equilibrium at levels below or above full employment. Recessionary gap: the economy is operating with less than full employment, i.e., high unemployment Expansionary gap: the economy is operating with more than full employment, i.e., low unemployment 18 Economic expansion or recession? Price Level (P) a. Expansion b. Recession c. Cannot be determined SRAS P AD 0 Y Quantity of Output (Y) 19 Expansionary or Recessionary (I) Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS a. Expansionary gap b. Recessionary gap P AD 0 Y* Y Quantity of Output (Y) 20 Expansionary or Recessionary (II) Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS P a. Expansionary gap b. Recessionary gap AD 0 Y Y* Quantity of Output (Y) 21 Recession A recession is a general slowdown in economic activity over a long period of time, or a business cycle contraction. During recessions, many macroeconomic indicators vary in a similar way. Production falls Gross Domestic Product (GDP), employment, investment spending, capacity utilization, household incomes, business profits and inflation Bankruptcies and the unemployment rate rises. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recession 22 Why do we care about business cycles? While we may love expansion but we would not want to experience recession. Most of us are risk averse and prefer stable income Implications for policy makers A good understanding of the cycles helps us prevent it or reduce the magnitude of the cycles. Implications for individual consumers and investors A good understanding of the cycles helps us predict the cycles and hence prepare for the cycles. 23 Predictors of a recession In the US a significant stock market drop has often preceded the beginning of a recession. Inverted yield curve uses yields on 10-year and three-month Treasury securities as well as the Fed's overnight funds rate. Another model developed by Federal Reserve Bank of New York economists uses only the 10-year/three-month spread. It is, however, not a definite indicator; it is sometimes followed by a recession 6 to 18 months later. The three-month change in the unemployment rate and initial jobless claims. Index of Leading (Economic) Indicators (includes some of the above indicators). Lowering of Home Prices. Lowering of home prices or value, too much personal debts. 24 Causes of business cycles The cause of a business cycle typically is taken to be a shock or innovation to a relationship in the economy. Only deviations from the rule then would be admissible as a shock. Shocks are defined according to specific models. http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/conf/conf42/con42_03.pdf 25 Example of shocks An elementary open-economy model: an augmented IS-LM model or Mundell-Fleming model. The model distinguishes domestic and foreign shocks as well as real and monetary shocks. This level of abstraction and general orientation of underlying assumptions about the economy is typical of the historical literature on business cycles in the United States. Domestic Foreign Real DR FR Monetary DM FM http://www.bos.frb.org/economic/conf/conf42/con42_03.pdf http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mundell-Fleming_model 26 Recessionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 P2 B A P1 Higher price Lower output Lower employment Higher unemployment AD1 0 Y2 Y1 Quantity of Output (Y) 27 Recessionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 A P1 B P2 Lower price Lower output Lower employment Higher unemployment AD2 0 Y2 Y1 AD1 Quantity of Output (Y) 28 Expansionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 Higher price Higher output Higher employment Lower unemployment B P2 A P1 AD1 0 Y1 Y2 AD2 Quantity of Output (Y) 29 Expansionary gap Price Level (P) LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 A P1 B P2 Lower price Higher output Higher employment Lower unemployment AD1 0 Y1 Y2 Quantity of Output (Y) 30 Business Cycle Dating in the US The National Bureau's Business Cycle Dating Committee maintains a chronology of the U.S. business cycle. The chronology identifies the dates of peaks and troughs that frame economic recession or expansion. The period from a peak to a trough is a recession and the period from a trough to a peak is an expansion. The NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. Rather, a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales. http://www.nber.org/cycles.html http://www.nber.org/cycles/recessions.html 31 Identifying the trough in November 2001 On July 16, 2003, the committee determined that a trough in economic activity occurred in November 2001. The committee's announcement of the trough is at http://www.nber.org/cycles/july2003. On November 26, 2001, the committee determined that the peak of economic activity had occurred in March of that year. For a discussion of the committee's reasoning and the underlying evidence, see http://www.nber.org/cycles/november2001. Thus, March 2001 (peak) to November 2001 (trough) was a recession. http://www.nber.org/cycles/recessions.html 32 The committee’s usual procedures in identifying trough Because a recession influences the economy broadly and is not confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity. The committee views real GDP as the single best measure of aggregate economic activity. In determining whether a recession has occurred and in identifying the approximate dates of the peak and the trough, the committee therefore places considerable weight on the estimates of real GDP issued by the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The traditional role of the committee is to maintain a monthly chronology, however, and the BEA’s real GDP estimates are only available quarterly. For this reason, the committee refers to a variety of monthly indicators to choose the exact months of peaks and troughs. 33 The committee’s usual procedures in identifying trough It places particular emphasis on two monthly measures of activity across the entire economy: (1) personal income less transfer payments, in real terms and (2) employment. In addition, the committee refers to two indicators with coverage primarily of manufacturing and goods: (3) industrial production and (4) the volume of sales of the manufacturing and wholesaleretail sectors adjusted for price changes. The committee also looks at monthly estimates of real GDP such as those prepared by Macroeconomic Advisers (see http://www.macroadvisers.com). Although these indicators are the most important measures considered by the NBER in developing its business cycle chronology, there is no fixed rule about which other measures contribute information to the process. 34 Figure 1: Quarterly Real GDP The fact that this broad and reliable indicator of macroeconomic activity surpassed its previous peak in the fourth quarter of 2001 was a key reason that the committee felt that the recession that began in March 2001 had ended. … The fact that quarterly real GDP grew very strongly in the fourth quarter of 2001 also helped to limit the possible months that could be identified as the trough. The committee felt that the recovery must have begun before December 2001 for GDP to have grown so rapidly in the fourth quarter. 35 Figure 2: Real Personal Income less Transfers The behavior of this series is consistent with both the identification of a trough and the placement of the trough in November 2001. Real personal income fell in early 2001. It reached its low point in October 2001. However, because it grew only a small amount between October and November 2001, the NBER methodology indicates that it reached its trough in November. Since then, personal income less transfers generally rose through January 2003, fell in February and March, but rose in April and May, the most recent reported months. 36 Figure 3: Payroll Employment The fluctuations in this series are quite different from those in the broader, output-based measures. Employment reached a peak in February 2001 and declined through July 2002. It rose slightly through November, took a sharp downturn in December, rose again in January 2003, but since then has declined through June 2003, the most recent reported month. It is now 394,000 below the start of the year, and 2.6 million below the February 2001 peak. The fact that employment has continued to decline while output-based measures have risen reflects the fact that productivity has risen substantially since late 2001. The divergent behavior of output and employment was a key reason why the committee waited a long time before identifying the trough. 37 Why identified November 2001 as trough with conflicting data? The behavior of other monthly series is also consistent with the identification of the trough in late 2001. Industrial production fell until December 2001 and then rose rapidly until July 2002. It has fallen slightly since then. Real manufacturing wholesale-retail sales reached its low in September 2001. It then recovered substantially in October 2001, only to fall again in November. As discussed in the trough announcement, the NBER methodology holds that extreme events, such as strikes and natural disasters, that affect particular monthly observations should be downweighted in identifying business cycle turning points. For this reason, the committee emphasized the November 2001 trough in this series, rather than the dramatic decline in sales following the tragic events of September 11th. This series has generally risen since September 2001. It fell sharply in February 2003, but rose substantially in March, the most recent reported month. The committee also looks at monthly estimates of real GDP provided by Macroeconomic Advisors. This series reached its low in September 2001 and has generally been growing since then. The fact that monthly GDP rose dramatically in December 2001 reinforced the committee’s decision that the trough occurred in November. Monthly real GDP fell slightly in March and April 2003, the most recent reported months. 38 NBER recession dates http://www.nber.org/cycles.html Peak Trough Contraction Expansion Cycle P-P T-T August 1929(III) March 1933 (I) 43 21 64 34 May 1937(II) June 1938 (II) 13 50 63 93 February 1945(I) October 1945 (IV) 8 80 88 93 November 1948(IV) October 1949 (IV) 11 37 48 45 July 1953(II) May 1954 (II) 10 45 55 56 August 1957(III) April 1958 (II) 8 39 47 49 April 1960(II) February 1961 (I) 10 24 34 32 December 1969(IV) November 1970 (IV) 11 106 117 116 November 1973(IV) March 1975 (I) 16 36 52 47 January 1980(I) July 1980 (III) 6 58 64 74 July 1981(III) November 1982 (IV) 16 12 28 18 July 1990(III) March 1991(I) 8 92 100 108 March 2001(I) November 2001 (IV) 8 120 128 128 December 2007 (IV) 73 81 39 Suggested exercises Go through the NBER’s Business-Cycle Dating Procedure in class. Exercise #1: Give students some US data up to different point in time (available at the St. Louis Fed, http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/). Let them work in groups and determine the most recent trough or peak. Exercise #2: Give students some Hong Kong data up to certain time (available at http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/hong_kong_statistics/index.jsp). Let them determine the most recent trough or peak. ** Re-label the dates if we are concerned that students may remember the recession dates previously identified by the official announcements. 40 Shiskin’s Rules of Thumb for Spotting a Recession (two-quarter rule?) Real GDP declines for two successive quarters Industrial production declines for a 6-month period. Real GDP declines by at least 1.5% Payroll employment declines by at least 1.5% At least two-point rise in unemployment rate For six months or longer, less than 25% of the industries are expanding when measured by the employment diffusion index using 6-month spans. The Bureau of Labor Statistics employment diffusion index covers 274 industries and asks this question: What share of the industries are enjoying an employment expansion or experiencing a contraction? A reading of 50 indicates exact balance. Values below 50 indicate contraction. 41 5 0 -5 Percentage 10 15 Hong Kong Recessions Year-on-year Growth rate of Real GDP (chained) 1973 1977 1981 1985 1989 1993 1997 2001 2005 2009 Time 42 HK recessions Unemployment rate 1981:10 - 2009:09 2009:08 2009:09 SA 5.4 5.3 NSA 5.8 5.6 43 Hong Kong’s dependence on the US Monthly seasonally adjusted unemployment rate from 1981 October to 2009 August is obtained from the online statistical tables of Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department, a total of 335 observations. The data are plotted with NBER recession dates. 44 Hong Kong’s dependence on the US 2 4 Percent 6 8 Hong Kong Unemployment Rate 1981:10 - 2009:8 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 45 Hong Kong’s dependence on the US Hong Kong’s unemployment rate tend to increase during episodes of US recessions. The negative impact of the US recession or downturn on Hong Kong takes a couple of months to realize. 46 Understanding recession We have to understand expansion 47 How do bubbles cause cycles? Higher asset prices Consumption increases due to wealth effect Aggregate demand increases Output increases 48 How does excess liquidity cause a boom? Excess liquidity and easy credit Higher asset prices Consumption and investment increase Consumption increases due to wealth effect Aggregate demand increases Output increases 49 Causes of the financial crisis? Influx of Foreign Money Low interest rates Easy credit market Great demand for Financial products High consumption Unprecedented debt load •Property appreciation •easy initial terms & ARM Financial Bubbles Housing bubbles •Free cash from refinancing SEC relaxed capital rule prompted banks take on higher leverages. Encouraged subprime mortgages, incl. Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac. Mortgagebacked, highly leveraged, complex & hardto-value financial innovations e.g. MBS, CDO, CDS Kept derivatives market unregulated. U.S. Govt. Underestimated the impacts of shadow banking systems, i.e. investment banks and hedge funds, which lacked financial cushions. Accounting practices allowed commercial banks to move new financial products off balance sheets as complex legal entities. 50 A note on the financial innovations Subprime lending means lending towards those borrowers with weak credit histories; thus it has greater risks of loan defaults. Mortgaged-backed securities (MBS) are securities derive their values from mortgages payments and housing prices. A Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO) bundles cash payments from multiple mortgages or other debt obligations into a single pool, from which the cash is allocated to specific securities in a priority sequence. A Credit Default Swap (CDS) involves an insurance party, such as AIG, receiving a premium in exchange for a promise to pay money to party A (say an investment bank) in the event of party B (mortgage holder) defaulted. The risks inherent with the above financial derivatives were not accurately measured nor reflected by the issuers and rating agencies; nor fully understood by the investors. 51 How bubbled were the Housing Bubbles? Price of a typical American house increased by 124% from 1997 to 2006. U.S. home mortgage debt to GDP ratio increased from 46% in 1990s to 73% in 2008. The value of U.S. subprime mortgages was estimated at $1.3 trillion as of March 2007. It spiked to 20% of all mortgages in 2005 from 10% prior to 2004. Delinquency rates increased from 10-15% before 2006 to 25% in early 2008. As of Aug., 2009, 9.2% of all mortgages outstanding were either delinquent or in foreclosure. 52 How bubbled were the financial Bubbles? Between 1996 and 2004, the USA current account deficit increased by US$650 million, from 1.5% to 5.8% of GDP. The top five U.S. investment banks, plus Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, were estimated to have US$9 trillion in debt or guarantee obligations in 2008. These shadow financial institutions were not subject to the same depository banking regulations. The top four U.S. commercial banks were estimated to have to return between US$500 billion to US$1 trillion to their balance sheets in 2009. Volume of CDS outstanding increased 100-fold from 1998 to 2008, estimated at US$33 to $47 trillion as of Nov., 08. 53 Financial markets impacts (1) Troubled banks were nationalized (Northern Rock) or acquired (Merrill Lynch), if not gone bankrupt (Lehmann Brothers). The credit markets were paralyzed, so the U.S. government had to extend insurance for the money market accounts. A $700 billion emergency bailout program, Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), was signed into law in October, 2008 to stabilize the economy. It was estimated that Americans on average lost more than one quarter of their collective net worth from mid 2007 to late 2008, resulting from declines in consumption and business investment. 54 Financial markets impacts (2) The U.S. financial crisis rapidly spilled over and many European banks failed. The de-leveraging of financial institutions further worsened the liquidity crisis. Although Asia was not at the center of the financial crisis, weakened economies in the west caused a drastic decrease in international trade. For the 1st quarter of 2009, the GDP declined by 14.4% in Germany, 15.2% in Japan, 7.4% in the UK, 9.8% in the Euro, 21.5% in Mexico and 6% in the U.S.A. The unemployment rate in the U.S. was 9.5% by June 2009. 55 Short-term government remedies To avoid a global recession, collective actions were taken by many governments, including: Interest rates were at historical low Injected liquidity into the credit markets Purchased trillions of government debts and troubled private assets from banks Raised the capital of the national banks by purchasing newly issued preferred stock in major banks. 56 The current US recession When did the current recession start? http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html Has the recession ended? 57 Identifying the quarter of peak The product-side estimates fell slightly in 2007Q4, rose slightly in 2008Q1, rose again in 2008Q2, and fell slightly in 2008Q3. The income-side estimates reached their peak in 2007Q3, fell slightly in 2007Q4 and 2008Q1, rose slightly in 2008Q2 to a level below its peak in 2007Q3, and fell again in 2008Q3. Thus, the currently available estimates of quarterly aggregate real domestic production do not speak clearly about the date of a peak in activity. Other indicators reached peaks between November 2007 and June 2008: real personal income less transfer payments, real manufacturing and wholesale-retail trade sales, industrial production, and employment estimates based on the household survey. The decline in economic activity in 2008 met the standard for a recession http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html 58 Identifying the Month of the peak Payroll employment, the number of filled jobs in the economy based on the Bureau of Labor Statistics survey of employers, reached a peak in December 2007 and has declined in every month since then. An alternative measure of employment, measured by the BLS household survey, reached a peak in November 2007, declined early in 2008, expanded temporarily in April to a level below its November 2007 peak, and has declined in every month since April 2008. Real personal income less transfers peaked in December 2007, displayed a zig-zag pattern from then until June 2008 at levels slightly below the December 2007 peak, and has generally declined since June.? Real manufacturing and wholesale-retail trade sales reached a well-defined peak in June 2008. Industrial production peaked in January 2008, fell through May 2008, rose slightly in June and July, and then fell substantially from July to September. http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html 59 NBER recession dates http://www.nber.org/cycles.html Peak Trough Contraction Expansion Cycle P-P T-T August 1929(III) March 1933 (I) 43 21 64 34 May 1937(II) June 1938 (II) 13 50 63 93 February 1945(I) October 1945 (IV) 8 80 88 93 November 1948(IV) October 1949 (IV) 11 37 48 45 July 1953(II) May 1954 (II) 10 45 55 56 August 1957(III) April 1958 (II) 8 39 47 49 April 1960(II) February 1961 (I) 10 24 34 32 December 1969(IV) November 1970 (IV) 11 106 117 116 November 1973(IV) March 1975 (I) 16 36 52 47 January 1980(I) July 1980 (III) 6 58 64 74 July 1981(III) November 1982 (IV) 16 12 28 18 July 1990(III) March 1991(I) 8 92 100 108 March 2001(I) November 2001 (IV) 8 120 128 128 December 2007 (IV) 73 81 60 Additional readings about the crisis The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis maintains an excellent website about The recent Financial Crisis (http://timeline.stlouisfed.org/): The Financial Crisis: A Timeline of Events and Policy Actions The Financial Crisis: Glossary the current global recession (http://research.stlouisfed.org/recession/) the US data (http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/) Slightly more technical papers: Caballero, Ricardo, J. and Pablo Kurlat (2009): “The “Surprising” Origin and Nature of Financial Crises: A Macroeconomic Policy Proposal,” Paper presented at the Jackson Hole Symposium on Financial Stability and Macroeconomic Policy, August 20-22, 2009. Taylor, John B. and John C. Williams (2008): “A Black Swan in the Money Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2008-04. 61 Additional reading on Business Cycles The National Bureau of Economic Research keeps the past announcement of the business cycle dating Peak and trough dates and announcements: http://www.nber.org/cycles.html An illustration of the NBER Recession Dating Procedure: http://www.nber.org/cycles/recessions.html Niemira, Michael P. and Philip A. Klein (1994): Forecasting Financial and Economic Cycles, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Cotis, Jean-Philippe, and Jonathan Coppel (2005): “Business Cycle Dynamics in OECD Countries: Evidence, Causes and Policy Implications,” Paper presented at the Changing Nature of the Business Cycle, the Reserve Bank of Australia Economic Conference, July 11-12, 2005. Temin, Peter (1998): “The Causes of American Business Cycles: An Essay in Economic Historiography,” NBER Working Paper 6692. Stock, James H. and Mark W. Watson (1998): “Business cycle fluctuations in U.S. macroeconomic time series,” NBER Working Paper 6528. 62 End 63