- Sacramento

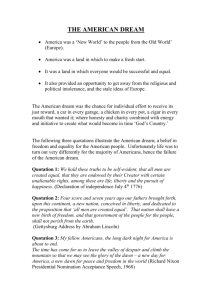

advertisement