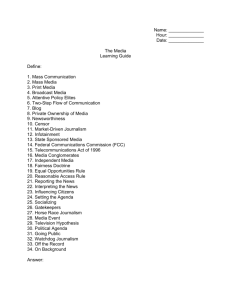

Broadcast News (1987) - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

Broadcast News (1987) Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University James L. Brooks • • • • • • Brooks briefly worked as a writer for CBS News in New York before moving to LA in 1966 to become a screenwriter. He had success in TV winning Emmys for writing various shows such as Taxi and The Mary Tyler Moore Show. He won three Academy Awards (writer/director/picture) for Terms of Endearment (1983). Almost 20 years after his 1960s CBS stint, he returned to the news business—not as a writer but as an observer. What evolved from his experiences was the screenplay for Broadcast News, a movie presenting worst-case scenarios for network news of the 1980s and foreshadowing broadcast news of the future. He went on to develop the Simpsons TV show and write and direct As Good as It Gets (1997) among other projects. Cynicism in the Post-Watergate Era • • • • In the post-Watergate era, many have argued that journalism developed a crisis of confidence against a landscape increasingly dominated by TV, infotainment, and celebrity obsession. Broadcast News challenges the mythic notion of journalism as a force for democratic good. The film is not about uncovering the truth or exposing the lie. Instead, it is a film about how we process the news; how accepting smaller human-interest stories, reported by stylized celebrity anchors, makes it easier to neglect the world at large. Aaron provides the critique when he compares Tom to the devil. He tells Jane that Satan will not appear in scary garb: “He will be attractive; he’ll be nice and helpful; he’ll get a job where he influences a great God-fearing nation; he’ll never do an evil thing…. He’ll just bit by little bit lower our standards where they’re important. Just a tiny little bit, just coast along—flash over substance! Just a tiny bit. And he will talk about all of us really being salesmen. And he'll get all the great women.” Dualities in Film: Work v. Home • • • • Romantic comedy is about love and marriage, which confirm traditional bonds and integrate individuals into the social and cultural order. In some ways, journalism movies subvert all that. While romantic comedies of the 1930s and 1940s show strong women finding romance without sacrificing their careers, the romantic comedies of the 1970s and 1980s show that women who strive for promotions will inevitably sacrifice love and romance. Jane’s inability to have a meaningful relationship with Tom or anyone else teaches the lesson: maybe women can’t “have it all.” Indeed, all three lead characters: Jane, Tom, and Aaron are frantic overachievers, careerists with an aching void at the center of their lives. The lesson is the workaholic culture of the 1980s leaves people personally bankrupt. Anti-Feminist? • Writer/Director James L. Brooks said, “I knew that I didn’t want to do a picture that could be in any way a feminist picture…. There was great effort given to presenting what I hoped was a new kind of heroine.” • A 1988 study of women in TV news reported: “After facing incredible competition to get into their positions and after working hard to get promoted [women] find themselves having to make difficult choices between their careers and personal lives.” • Many saw the film as anti-feminist by denying Jane true sexual intimacy. Yet women who worked in network news loved it and it inspired a new generation of young women to journalism careers. Dualities in Film: Public Interest v. Private Interest • • • 1. 2. The notion that journalists prey on and exploit their subjects often is validated by the movies such as with Tom’s interview with the woman who was raped. Yet journalists are also portrayed as heroes who uncover stories that others try to suppress or ignore and who uphold the public’s right to know. This is exemplified by Tom’s confrontation with the Army General. These conflicting depictions reflect conflicting myths: There is the belief that journalism should play a central role in the political process and that people need journalists’ help to govern themselves. That is in keeping with many or most journalists’ self-image and with official mythology. It is bound up with other beliefs: that we can govern ourselves, that citizens can influence events, that the system works, and that the truth will emerge. There is also the belief that journalism’s claims to being society’s appointed storytellers or arbiters of truth are full of bunk. That belief holds that the media and their vast technological apparatus disempower the citizenry and prop up the powerful at the expense of the powerless Consistent with outlaw mythology, it views the press as just another impersonal, oppressive institution that restricts individual self-determination and liberty. Holly Hunter as Jane • • • • • A talented producer on the rise in a Washington network news bureau, her personal life leaves much to be desired: she schedules regular intervals when she can have a good cry. Though she is a smart, responsible journalist, she is seduced both personally and professionally by television’s empty-headed glamour—as personified by Tom. She is another long-suffering professional insider whose uncommon intelligence only causes her grief. The news president tells her: “It must be nice to always believe you know better: to always think you’re the smartest person in the room.” She sadly replies: “No, it’s awful.” She is torn between the past (substantive news as represented by Aaron) and the future (style and glamour as represented by Tom). In the end, Jane wins a promotion as managing editor of the nightly news in New York but fails to find a steady romance. She reveals that “there’s a guy” who “says he’ll fly up a lot” to visit but we know that long-distance relationships among career-driven singles never work and so Jane is doomed to life of professional reward and the expense of personal unhappiness. The Real Jane Craig • • Brooks drew on several models for Jane, including CBS news producer Susan Zirinsky and correspondent Lesley Stahl, who was distressed when Brooks shared scuttlebutt he had heard from being around CBS. “I think you should know that your bosses consider your stiff, look-into-the camera style as ‘yesterday,’” Stahl remembered him telling her. “I’d hate to see you left in the dust.” While still in college, Zirinsky got a part-time job at CBS News. She recalled: “I was hired full time, while still a full time student. Who could turn it down? I can make it work. I noticed a tiny desk in the back hallway - a little messy but so tiny it looked like something out of Alice In Wonderland. It was CBS News reporter Lesley Stahl's. When I finally met the fully grown adult woman who occupied this itty bitty desk - I got it. She was the girl in the guy's world. Gender had never occurred to me until I saw it in play. But it became irrelevant. Stahl was a workhorse, passionate, driven to find out the truth about Watergate and the White House involvement. When I was lucky (there's that word again) enough to be hired full time - I was really lucky - Lesley Stahl became my mentor. I saw her work and, through sheer force of will, through a world that wasn't ready for her...but she was ready for it. Stahl was relentless and taught me that was really only the way to be. Stahl has gone on to become a legend in television news. She's covered the White House, campaigns, special assignments and of course now ‘60 Minutes.’ Lesley pushed me past the anxieties I had as the youngest person in the room. She would say, ‘you're not really a person till you're 25.’ In fact, she threw a coming-out party on my 25th birthday. Only problem, I couldn't make it. The Hanafi Muslims had taken over several buildings in Washington, D.C. and were holding hostages. I was pinned down by men with guns opposite the B'nai B'rith International Center in the middle of the nation's capitol. . I guess it was a very ‘Lesley Stahl’ type of experience and so my coming out party was just a different kind of party. William Hurt as Tom • Pretty-boy “journalist” who comes to the network from local TV sports and freely admits he knows nothing about news. • Yet he is ambitious and knows about the primacy of style and image in the coming infotainment era. He sends his tapes to the networks, gets hired, and sees in Jane someone he can use to further his career. • Tom represents the future of news. • In the end, he gets promoted and engaged to a blonde journalist who early in the movie had been heard disparaging Jane’s looks. Albert Brooks as Aaron • • • • • Aaron plays the smart but awkward reporter whose struggles to succeed in a profession increasingly dominated by corporate profits, infotainment, and celebrity. In the end, he takes the moral high road and quits rather than continue to be undervalued by his corporate bosses. Though his love for Jane is never realized, in the end he is able to find a workhome balance as a local reporter with a family – though it is not the work-home balance he ideally wanted with Jane and the network. The lesson is that one cannot succeed in climbing the corporate news ladder unless one is willing to sacrifice home, love, and family. Aaron represents the past, when presumably image and ratings were irrelevant. News is a Business • The commercial pressures associated with news are portrayed throughout the film from the discussion of whether to televise an execution, the dumb but pretty anchor who triumphs over smart but awkward reporter, or the layoffs from the “higher ups” despite the voices of conscience who decry what is happening, yet are powerless to stop it. Media Concentration • • • • • • • • • • • Is corporatization and media concentration a problem for journalism? In 1983, fifty corporations dominated most of every mass medium and the biggest media merger in history was a $340 million deal. … [I]n 1987, the fifty companies had shrunk to twenty-nine. … [I]n 1990, the twenty-nine had shrunk to twenty three. … [I]n 1997, the biggest firms numbered ten and involved the $19 billion Disney-ABC deal, at the time the biggest media merger ever. … [In 2000] AOL Time Warner’s $350 billion merged corporation [was] more than 1,000 times larger [than the biggest deal of 1983]. Mother Jones magazine reports that by the end of 2006, there were only 8 giant media companies dominating the US media, from which most people get their news and information: Disney (market value: $72.8 billion) AOL-Time Warner (market value: $90.7 billion) Viacom (market value: $53.9 billion) General Electric (owner of NBC, market value: $390.6 billion) News Corporation (market value: $56.7 billion) Yahoo! (market value: $40.1 billion) Microsoft (market value: $306.8 billion) Google (market value: $154.6 billion) Conclusion • • • • Broadcast News is both a romantic comedy and a commentary on journalism in transition in the post-Watergate era. Writer/Director Brooks said: “What the picture was about was three people who had missed their last chance at real intimacy in their lives.” While the men find partners in the end, the woman does not and will not. While professional men can at least find some level of romantic intimacy, professional women cannot. Women must make greater sacrifices for their careers than men. Similarly, journalism was forced to reject or at least significantly compromise the hard news, substantive past in favor of the profitdriven, style of the future. The film is titled Broadcast News to point out that there is a difference between what is broadcast... and what is news. Sources • • • Cabin, Chris, “Broadcast News,” filmcritic.com, 2008. http://www.filmcritic.com/misc/emporium.nsf/reviews/Broadcast-News Ehrlich, Matthew C., Journalism in the Movies (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004). Pick, Lee Anne, “Style Over Substance: Broadcast News,” in Howard Good ed., Journalism Ethics Goes to the Movies (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008) 97-108