Draft One of Essay 1.0 (Word Doc)

advertisement

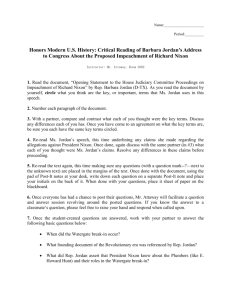

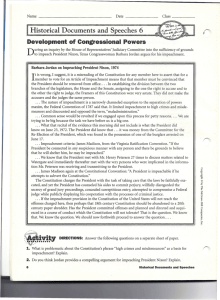

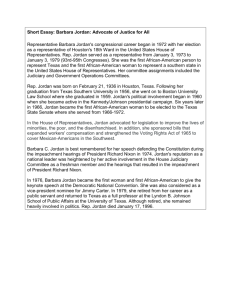

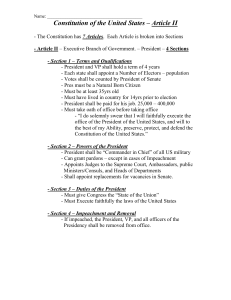

Sablan 1 Writing Frame Form Just like a picture hung on the wall looks the best when it is displayed in a frame that “fits” the picture, so too is writing at its best when it is written to fit inside its “frame.” The “frame” for writing consists of elements of the writing situation—your audience, your purpose, the genre in which you’re writing, and the time period in which you’re writing. These four elements compose a “frame” that allow you to craft the most effective piece of writing possible for the particular writing situation which you are attempting to address. For each piece you write in this class you will be asked to identify the “frame” in which you’re writing. Answer the following questions: 1. Who is your audience—in other words, who are you trying to write to? Be SPECIFIC! Don’t just say “general audience.” Aside from Sarah and my peer-response editors, I am trying to write to Black Americans of Barbara Jordan’s time and Black Americans of the present to gage their feelings and first-hand responses to Barbara Jordan’s speech, those interested in the Constitution and the execution of its principles, and to fans of rhetoric through political speeches. 2. What is your purpose—in other words, what effect do you want to have on your reader? I want my readers to understand that Jordan’s speech is so much more than eloquent in language and delivery, but that her reasoning and influence during the impeachment hearings makes very clear just how significantly the constitution’s interpretations has affected her race and what it would mean if the impeachment provisions didn’t condemn Nixon’s offenses. 3. What genre are you writing in? What are some of the conventions of this genre that might be important to consider as you begin your writing process? I read online somewhere that a “multi-genre paper arises from research, experience, and imagination.” I would like to think I am writing a multi-genre research essay (as I try to incorporate research of the events/people, my personal experience and exploration of my claim, and imagination to write with a style appropriate and serious enough to discuss a very serious topic.) 4. How is your topic relevant to your audience NOW in the time period in which you’re writing? Barbara Jordan’s speech is ingrained in America’s rhetorical history because it paints a very clear picture of the experience of a race and its change over time, the application of the Constitution and how it would cease to matter if its provisions are ignored, her skills as an orator, and her impact as a representative. Sablan 2 5. Given your audience and purpose, what kinds of evidence/support will you need/use to develop your purpose convincingly for your audience? To effectively convince my audience of my claim, I must have direct quotations from Jordan’s speech, context of the Watergate scandal, research of Barbara Jordan’s Ethos, and references to the actual provisions of impeachment from the U.S. Constitution. 6. How will you use YOUR own voice in this piece of writing? Why is YOUR voice important in this piece of writing? I can only make my claim my own by writing in my perspective. As we’ve discussed in class and read in the assigned article, my claim would differentiate itself from Jordan’s and make known to my readers that I personally believe in such a claim through evidence I find convincing. My introductions of Jordan and Nixon are written in third-person limited I suppose (I tried to stick with my summarization of facts and simply recalling events to set the context of Nixon’s impeachment hearings). Sablan 3 Christina Sablan Dr. Sarah M. Lushia WR 122 Honors 17 October 2014 Essay 1.0 First Draft Barbara Jordan’s Statement on the Articles of Impeachment In 1972, when the Vietnam War had left the United States severely divided, incumbent President Richard Nixon and his key advisors sought to run an aggressive and impetuous presidential campaign, employing evasive acts of illegal espionage. On June 17, 1972, members of Nixon’s Committee to Re-elect the President were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee office while attempting to steal top-secret documents and wiretap office phones. In an attempt to cover up his involvement in the operation, President Nixon bribed the burglars, destroyed evidence and intercepted the FBI’s investigation of the crime, and used his position to fire staff members unwilling to cooperate. When news of Nixon’s involvement in the scandal fully surfaced, he resigned in August of 1974 (“Watergate”). During Nixon’s impeachment hearings in 1974, an influential opening statement was delivered by Barbara Jordan, a member of the House Judiciary Committee. Barbara Jordan was the first African American to be elected in the Texas Senate after reconstruction, the first black female from the south to be elected to the United States House of Representatives, the first black female to deliver the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in 1976, a notable recipient of numerous honors such as the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and upon her death, Sablan 4 she became the first Black woman to be buried in the Texas State Cemetery (“Barbara”). In a society dominated by white males, Jordan has taken major strides as a Black American woman and a politician hailing from the south so shortly after the Reconstruction Era had transformed the Southern states. On July 25, 1974, Barbara Jordan delivered before the members of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee a fifteen minute opening speech (“Barbara”). In the beginning of her speech, she first acknowledges the impact of her personal context and how she and her race of people were not initially included in the Constitution’s “We, the people.” She reminds us that, through lengthy and contended processes of amendment, interpretation, and court decision, African Americans are now finally a part of that “We, the people.” She assures us that her “faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction, of the Constitution” (“American”). Considering Jordan’s background and the extent to which she had pursued her education and political career in the face of segregation (and the violent agitation that often follows integration), it is more than flooring the notion that one who pledges solemn allegiance to the Constitution after finally being included would opt to discard the text (“Barbara”). “If the impeachment provision in the Constitution of the United States will not reach the offenses charged here,” says Jordan near the end of her speech, “then perhaps that 18th-century Constitution should be abandoned to a 20th-century paper shredder!” (“American”). Her speech includes a series of comparisons between the criteria for impeachment as articulated in the Constitution and Nixon’s alleged crimes. Without actually condemning Nixon Sablan 5 or stating that he must be impeached, she suggests, through the criteria she clearly cites during her speech, that the Constitution be abandoned should Nixon’s actions be overlooked by the law. What would the subversion of the Constitution by Presidential maladministration make the grueling and painful journey that African Americans have taken in the process of becoming more than property but citizens? Futile. The significance of Barbara Jordan’s statement on the articles of impeachment lies in her firm defense of the Constitution and its system of checks and balances. She offers the undeniable basis for impeachment despite the Constitution’s previously inapplicable rights for African Americans Though Black American history felt the first wave of impact from Jordan’s speech (which was even more intense as her very presence in the House Judiciary Committee lends her interpretation more weight), its significance also resonates in Mainstream American history. The eloquence and influence of her speech has, since it had been first delivered, transcended far beyond the attention of Black Americans. She illustrated for the audience of her speech the image of a Doctrine of principles, with rights freshly inherited by Black Americans and with interpretations that have afforded their ancestors the darkest oppression. She demonstrates that the Constitution truly deserves to be maintained, to be defended. She describes this image as one with complete allegiance to its fundamental principles, and as one with resolute understanding of what it means to be and not to be included in it. I personally find that Jordan offered me, a spectator of a very different generation and race, a cultural lens through which the importance of the Constitution’s provisions is shone under a different light. I have experienced nothing but the inclusion the Constitution offers its citizens, so putting myself in her position feels unfamiliar and painful. Painful in that I would not know Sablan 6 how to react to the committee that chooses not to impeach a president who so overtly breaks code(s) of conduct. To ignore the staunch and unfaltering reason in Jordan’s speech would demean the document elicited by our founding father’s intent of fairness and democracy. Not only would it be a collapse of Democracy but it rids the Constitution of purpose. I believe Barbara Jordan’s speech is significant to Black American history because if the offenses were left uncharged by the impeachment provisions, then the result would prove the unfair application of its principles. This would mean the tragic history of a people, whose very lives were controlled in society by the fundamental liberties they were not allowed, had occurred for naught, if the Constitution’s content may be so easily null and voided. Sablan 7 Works Cited “American Rhetoric: Barbara Jordan – Statement on House Judiciary Proceedings to Impeach President Nixon.” American Rhetoric: Barbara Jordan – Statement on House Judiciary Proceedings to Impeach President Nixon. American Rhetoric, n.d. Web. 17 Oct. 2014. “Barbara C. Jordan.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 15 Oct.2014. “Watergate Scandal.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 15 Oct. 2014. Sablan 8