Deontology & Kantian Ethics: A University Presentation

advertisement

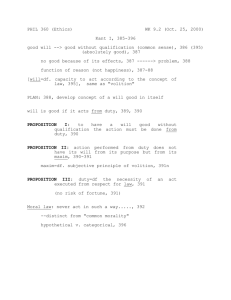

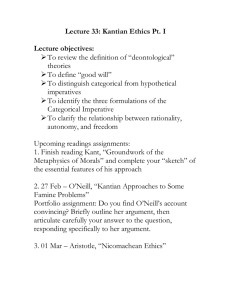

Deontological Approach Dr. Ching Wa Wong City University of Hong Kong saching@cityu.edu.hk 1 Using a person: a preliminary exercise The trolley problem again. Give a record of you feelings after seeing the following pictures. 2 3 4 Ching Wa pushed you! Help! 5 Part 1 Kant and deontological ethics 6 Deontology The theory of duty or moral obligation. Duty: Role-related duty General duty Obligation: Requirement set on a person because of his/her identity. 7 Basic Kantian themes 1. Personal autonomy: The moral person is a rational self-leglislator. 2. Respect: Persons should always be treated as an end, not a means. ‘No persons should be used.’ 3. Duty: the moral action is one that we must do in accordance with a certain principle, not because of its good consequence. 8 Kant’s philosophy: What can I know? Critique of Pure Reason (1781) What ought I do? Groundwork for the Metaphysic of Morals (1785); Critique of Practical Reason (1788) What can I hope for? Critique of Judgment (1790); Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone (1793) Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) 9 Phenomena and Noumena Phenomena: things as they appear to us; empirical and therefore changeable. Noumena: things-in-themselves, which can’t be known by the use of senses. Kant argues that if there is such a thing as moral reality, it must be founded on the noumena, and this is because… 10 The moral law is in its character absolute, and it can allow no exception. And empirical knowledge simply cannot establish such a law. 11 Part 2 Kant’s Conception of Moral Values 12 The moral worth On Kant’s view, the moral worth of an action is not determined by its consequences because: 13 1. It is possible that someone does something out of evil intention, but ends up bringing good consequences to society. 2. It is also possible that someone does something out of good intention, but ends up bringing about bad consequences. 3. The consequences of an action are not under our control. 4. We can only control our motives when acting as a moral person. 5. Therefore the moral worth of an action is given by our good will. 14 15 The right motive ‘For example, it is always a matter of duty that a dealer should not over charge an inexperienced purchaser; and wherever there is much commerce the prudent tradesman does not overcharge, but keeps a fixed price for everyone, so that a child buys of him as well as any other. Men are thus honestly served; but this is not enough to make us believe that the tradesman has so acted from duty and from principles of honesty: his own advantage required it; 16 it is out of the question in this case to suppose that he might besides have a direct inclination in favour of the buyers, so that, as it were, from love he should give no advantage to one over another. Accordingly the action was done neither from duty nor from direct inclination, but merely with a selfish view.’ (http://eserver.org/philosophy/kant/metaphys-of-morals.txt) 17 The right motive can be a motive out of either: self-interest, sympathy (natural inclination), or a sense of duty (the voice of conscience). Only the final motive will count on Kant’s view. 18 Hypothetical Vs categorical imperatives Hypothetical imperative: What I ought to do if some conditions hold. E.g., Maxim: I ought to attend the lecture if I want to pass my examination. Categorical imperative: What I ought to do unconditionally. E.g., Maxim: I ought not to murder no matter what goal I have. 19 Two formulations of the categorical imperative Act only on that maxim that you can will as a universal law. 2. Always treat humanity, whether your own person or that of another, never simply as a means but always at the same time as an end. 1. 20 One Kant’s view, all moral imperatives are categorical imperatives. They are universally valid and have equal forces to EQUALLY FREE and RATIONAL AGENTS. 21 An example: why lying is wrong If we use consequences as the basis of moral worth, sometimes lying is right because it makes a lot of people happy. But the maxim that supports lying cannot pass the ‘universality test’ and the ‘humanity test’. 22 Lying is wrong because: If everybody lies, then words lose its function to express truth. The principle of lying therefore cannot be universalized. 2. Lying can be successful only if we use other people’s ignorance. But in this case we are treating them only as a means to our ends. 1. 23 Freedom and the kingdom of ends Given that all rational beings are equal, a kingdom comprising those beings must not favour any party or treat the other as inferior. It follows that in the kingdom of ends everybody should be equally free and should not be a means to other people’s end. The law thus set up is a contract between free and rational agents. 24 Morality is thus a matter of social contract made between free and rational agents. 25 Part 3 Questions about Kantian Ethics 26 Motivational problems Why should I obey to the moral law? Answer: Because I want to be a wholly free (autonomous) person who acts on the principle that I find most reasonable. Why should I respect other persons? Answer: This is simply because rational persons are equal. 27 Freedom or equality? Is autonomy or equality the fundamental value in ethics? What if they conflict each other? Answer: In principle they do not conflict each other, because both are built up in the idea of reason. But in practice…? 28 Conflicts of duties If duty A conflicts with duty B, how can they be universalized? Example: I have a universal duty not to kill the Fat man. I also have a universal duty to save the five workers. What should I do? 29 Non-rational beings The moral law is set up by rational agents who mutually respect each other. Non-rational beings such as animals are not protected by that law because they don’t have this sense of responsibility. If we have a duty not to be cruel to animals, it cannot be for their sake, but for the reason that we will hurt our own rationality in doing so (that we will develop a bad personality in this practice). 30 Some questions to consider If I am a Kantian, should I support: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Participatory democracy? Representative (market) democracy? Capitalism? Revolutionary Marxism? Confucian ethics? Anarchism? 31 Part 4 Application: Research ethics 32 Using human beings in experiments Stanley Milgram’s experiment Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Study Main question: When will be wrong to use a person in academic research? 33 The doctrine of informed consent The Nuremberg code: The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential. This means that the person involved should have the legal capacity to give consent; should be so situated as to be able to exercise free power of choice, without the intervention of any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, over-reaching, or other ulterior form of constraint or coercion; and should have sufficient knowledge and comprehension of the subject matter involved as to enable him to make an understanding and enlightened decision. 34 Autonomy: A Kantian interpretation By saying that we respect persons as autonomous agents, we imply that they are having equal statuses with us, that we cannot treat them as a means only. Using somebody implies an imbalanced power structure, meaning that the users are in a higher rank; have more power; have ends in the action plan that the inferior party cannot share. 35 Autonomy thus requires that if I am to be treated as a means, I must also be able to recognize the experimenter’s end as my end. If I can recognize the promoting of collective interests as an end that I share without contradiction, I can say being deceived is my choice. 36 Milgram’s experiment I am a learner. And I have to remember the …SNOOPY words of the teacher and read them back. Teacher, give him a punishment. A 15 volt electric shock. APPLE--PEACH; LEMON—HONEY; CAR—TRASH; DEMOCRACY—PLATO; I am a teacher now. CHINGWA-CHINGWA—TEDDY BEAR… Wrong! Move on to the next word! If the answer is you say… Another In You If itthe isgive are experiment incorrect… participant, hired the learner bycorrect, an you after experimenter some play drawing the words partthe to toofremember, conduct lot, a teacher. plays an experiment. and ask thehim parttoofread a learner. out after some time. 37 The punishment part High voltage: 450 Dangerous Low voltage: Medium voltage: 15 Do it. I am in 250 charge of all this. are in regret. control of a instructing machine generating a TheYou experimenter You keeps ‘Why didn’t I stop, you man?’ to increase You do15 it accordingly. voltage ranging from to full 450 volts.great pain. The learner screams and shows voltage, saying that he takes responsibility for that. 38 Milgram’s trick You fooled me? No one in fact got hurt. The learner is a great pretender. You are cheated, man. There’s no electric shock at all. You lucky are angry. think it is unethical. The thing,You or the bad thing is that… 39 The Stanford Prison: A case study 40 Final questions Which experiment is more unethical according to Kantian ethics? Is the respect to autonomy something absolute? Is a lesser degree of autonomy totally unacceptable? How can we respect people when they are not fully rational? 41 References Driver, Julia, Ethics: the Fundamentals, Blackwell Publishing, ch.5 Mackinnon, Barbara (2007), Ethics: Theory and Contemporary Issues, Thomson Wadsworth, ch.5. Rachels, James (1995), The Elements of Moral Philosophy, McGraw-Hill, ch.9 & 10. 42