crucible notes

advertisement

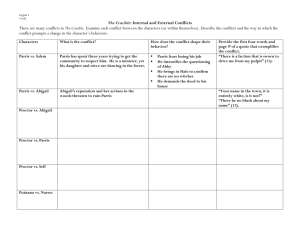

Website for “60 second summaries: http://www.60secondrecap.com/library/the-crucible/1/ In order to understand how reasonable people could allow themselves to take part in the miscarriage of justice that the Salem witch trials represent, we need to consider the kind of society the Puritans created in Salem Village. Massachusetts was different from the other colonies in that it was a theocracy (a commonwealth dominated by theology). Their system of governance was founded on and designed to preserve their religious principles. The Puritans believed they were God’s chosen people on an errand in the wilderness (literally believed they were establishing a New Jerusalem). The Puritans feared the wilderness: originally they tried to convert the Natives in the area, but when they resisted the Puritans decided the Natives were agents of the Devil who needed to be destroyed. Although witchcraft charges were common at the time, no other community experienced such widespread panic and terror. There were feuding factions within the community who used the terror to further their own causes. Friction among the residents and political instability of the village (under siege by the Natives) give us the motives of the adults. But what about the children? The presence of Tituba among the girls, society’s oppression, religious belief and fear of prosecution, a sense of impending doom from Native raids and the political instability (mixed with the rivalries of the village) all combined to produce the social paranoia that fueled the witch hunts. After WW2, Americans realized the Soviet Union was a powerful and potentially dangerous adversary. This view was seemingly confirmed by the news of Soviet nuclear capability. Riding the wave of popular opinion, Senator McCarthy created a stir and rose to national prominence by announcing to the media that he had information proving that high ranking officers and executives in the U.S. State Department and in the military were communists. His unsupported allegations gave rise to congressional investigations. In all walks of life (film and television, business, education, government) innocent people were unjustly persecuted for their views. Many were fired from their jobs simply for being suspected of being a communist! Although McCarthy had a few years of celebrity, he was eventually proved to be a fraud. The “Red Scare” ended, but not before many people had their lives, families and careers destroyed. Leviticus 16:20-22 20 “And when he has made an end of atoning for the Holy Place and the tent of meeting and the altar, he shall present the live goat. 21 And Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins. And he shall put them on the head of the goat and send it away into the wilderness by the hand of a man who is in readiness. 22 The goat shall bear all their iniquities on itself to a remote area, and he shall let the goat go free in the wilderness. Scapegoat: A person, group, or thing that bears the blame for the mistakes or crimes of others. Witch-hunt: An attempt to find and publicly punish people, usually whose opinions are considered to be subversive and dangerous. The rumour that Betty is the victim of witchcraft is running rampant in Salem, and a crowd has gathered in Parris’s parlor. Parris has sent for Reverend John Hale of Beverly, an expert on witchcraft, to determine whether Betty is indeed bewitched. Abigail denies that she and the girls engaged in witchcraft to Rev. Parris but then coaches the girls about what to say publicly. In Puritan Salem, young women such as Abigail, Mary, and Mercy are largely powerless until they get married. Proctor, in his first appearance, is presented as a quickwitted, sharp-tongued man with a strong independent streak. These traits would seem to make him a good person to question the motives of those who cry witchcraft. His guilt over his affair with Abigail makes him guilty of the hypocrisy that he accuses others of and weakens his resolve at key times. During his disagreement with Rev. Parris we see that any time one argues with the church they are accused of “doing the Devil’s work”. Reverend Hale is an intellectual man, and he has studied witchcraft extensively. He arrives at Parris’s home with a heavy load of books. Townsfolk immediately begin questioning him about various behaviours their spouses or neighbours have been showing to see if there is an evil influence at work. Upon questioning Abigail, Tituba gets accused which leads to a snowball effect. Once there is a confession (and forgiveness) the others quickly begin adding their parts to get out of any possible punishment. Abigail and her troop have achieved an extremely unusual level of power and authority for young, unmarried girls in a Puritan community. They can destroy the lives of others with a mere accusation, and even the wealthy and influential are not safe. Mary Warren is so full of her newfound power that she feels able to defy Proctor’s assumption of authority over her. Proctor’s sense of guilt begins to eat away at him. He knows that he can bring down Abigail and end her reign of terror, but he fears for his good name if his hidden sin of adultery is revealed. Proctor’s intense dilemma over whether to expose his own sin to bring down Abigail is complicated by Hale’s decision to visit everyone whose name is even remotely associated with the accusations of witchcraft. Hale, meanwhile, is undergoing an internal crisis. He clearly enjoyed being called to Salem because it made him feel like an expert. His pleasure in the trials comes from his privileged position of authority with respect to defining the guilty and the innocent. However, his surprise at hearing of Rebecca’s arrest and the warrant for Elizabeth’s arrest reveals that Hale is no longer in control of the proceedings. The desperate attempt by Giles, Proctor, and Francis to save their respective wives exposes the extent to which the trials have become about specific individuals. Danforth and Hathorne do not want to admit publicly that they were deceived by a bunch of young girls, while Parris does not want the trials to end as a fraud. the judge and the deputy governor react to Proctor’s claims by accusing him of trying to undermine the court. In order to dispose of Proctor’s threat, Danforth and Hathorne exercise their power to invade his privacy. Although Proctor has not yet been formally accused of witchcraft, Danforth and Hathorne, like Hale earlier, question him about his Christian morals as though he were already on trial. They hope to find in his character even the slightest deviation from Christian doctrine because they would then be able to cast him as an enemy of religion. Much of Act III has to do with determining who will define innocence and guilt. Proctor makes one desperate bid for this by finally overcoming his desire to protect his good name, exposing his own secret sin. He hopes to replace his wife’s alleged guilt with his own guilt and bring down Abigail in the process. Unfortunately, he mistakes the proceedings for an actual search for the guilty, when, in fact, the proceedings are better described as a power struggle. Months have passed, and things are falling apart in Massachusetts, making Danforth and Hathorne increasingly insecure. They do not want to, and ultimately cannot, admit that they made a mistake in signing the death warrants of the nineteen convicted, so they hope for confessions from the remaining prisoners to insulate them from accusations of mistaken verdicts. Clearly, the most important issue for the officials of the court is the preservation of their reputations and the integrity of the court. As a theocratic institution, the court represents divine, as well as secular, justice. To admit to twelve mistaken hangings would be to question divine justice and the very foundations of the state and of human life. Proctor fixates on his name and on how it will be destroyed if he signs the confession. Proctor’s desire to preserve his good name earlier keeps him from testifying against Abigail, leading to disastrous consequences. His goodness and honesty, lost during his affair with Abigail, are recovered. FULL TITLE · The Crucible AUTHOR · Arthur Miller TYPE OF WORK · Play GENRE · Tragedy, allegory TIME AND PLACE WRITTEN · America, early 1950s DATE OF FIRST PUBLICATION · 1953 NARRATOR · third-person narrator who fills in the background for the characters. CLIMAX · John Proctor tells the Salem court that he committed adultery with Abigail Williams. PROTAGONIST · John Proctor ANTAGONIST · Abigail Williams SETTING (TIME) · 1692 SETTING (PLACE) · Salem, · Serious and tragic—the language is almost biblical. THEMES · Intolerance; hysteria; reputation MOTIFS · Empowerment; accusation, confession, legal proceedings in general SYMBOLS very few examples of symbolism beyond typical witchcraft symbols (rats, toads, and bats), the entire play is meant to be symbolic, with its witch trials standing in for the anti-Communist “witchhunts” of the 1950s. a small town in colonial Massachusetts POINT OF VIEW · The Crucible is a play, so the audience and reader are entirely outside the action. FALLING ACTION · The events from John Proctor’s attempt to expose Abigail in Act IV to his decision to die rather than confess at the end of Act IV. TENSE · Present TONE