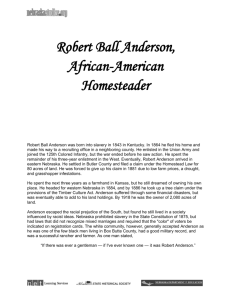

Anderson's Imperative.

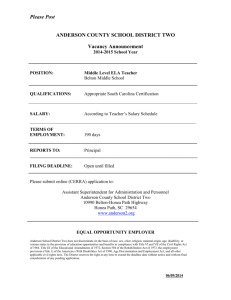

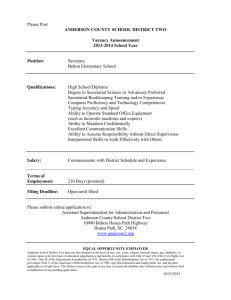

advertisement