Theories of the Good Life

advertisement

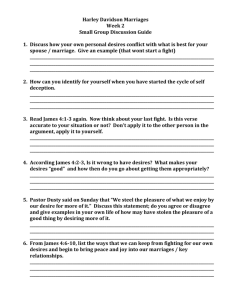

Theories of the Good Life Shane Ryan s.g.ryan@sms.ed.ac.uk 27/09/13 Seminar Goals ● Course Introduction ● Comments on analytic methodology ● Set out and offer critical evaluation of theories of the good life Course Introduction Themes in Ethics and Epistemology ● ● ● Ethics – topics include “Theories of the Good Life”, “Virtue Ethics”, “Why Be Moral?”. Epistemology – topics include “the Gettier case”, “Virtue Epistemology”, “the Value of Knowledge”. An underlying focus of the course is virtue approaches. Course Introduction Core Course Resources ● ● ● Shafer-Landau, R. Ethical Theory: An Anthology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Pritchard, D. What is this Thing Called Knowledge?. London and New York: Routledge, 2006. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu. Analytic Methodology: some characteristic features Intuitions ● Intuitions in analytic philosophy are generally treated as carrying prima facie evidential weight. – A typical use of intuitions is in response to cases/examples. Analytic Methodology: some characteristic features Intuitions ● ● It counts as a mark in favour of a philosophical account if that account can make sense of our intuitions. – Making sense of our intuitions can mean cashing out why our intuitions are right or diagnosing why they are misleading, or why some intuitions are right and others are misleading. – A counterintuitive account, by virtue of its claims or conclusion, has more to do to persuade us. Literature on use of intuitions: See Goldman 2007, Sosa 2007, and Stich 1988. Analytic Methodology: some characteristic features Expression of Ideas ● ● Everyday words are used and technical terms tend to be avoided if practical. Papers tend to follow the structure of identifying an issue/problem and addressing that issue/problem by way of a clear, logical argument. Theories of the Good Life Lecture Structure ● 1. The Issue ● 2. Hedonism ● 3. The Experience Machine ● 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory ● 5. Objective List Theory ● 6. Conclusion 1. The Issue ● What makes someone's life go well for them? Or, what factors are relevant when considering how well someone's life has gone for them – ● Sometimes this topic also comes under the heading of “well-being”. For example, what criterion or criteria should be used to say whether Sigmund Freud had a good life? 1. The Issue Preview of Possible Answers ● ● ● Is what's relevant the pleasure/happiness a person has over the course of their life? (Hedonism) Or is it the desires that were satisfied that is relevant? (Desire-fulfilment theory) Or is there an objective list of goods, including perhaps friendship, knowledge and achievement, that all bear on how well someone's life has gone. (Objective list theory). 2. Hedonism ● ● What matters is pleasure and pain. Goods such as friendship and achievement are only valuable in so far as they contribute to a person's pleasure. (They are instrumentally valuable, whereas pleasure is intrinsically valuable.) – One hedonist strategy is to say that aiming at such goods is a good way of bringing pleasure to a person's life. (Moore, 2004). ● But why, the hedonist may rhetorically ask, think that such goods are valuable, if a person derives no pleasure from them? 2. Hedonism General notes ● Jeremy Bentham and J.S. Mill are proponents – ● Mill adds that we should also consider the quality of the pain had. – ● Mill (1859) agrees that in calculating how well someone's life has gone we should consider the duration and intensity of the pleasure (and pain) had. This provides a way for him to respond to the charge that “hedonism is the doctrine of the swine”. Feldman (2002) defends attitudinal hedonism – enjoying what you get. 3. The Experience Machine ● “Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life's experiences?” (Nozick, 1974). 3. The Experience Machine Further points about the experience machine ● ● ● You can select from a broad catalogue of possible experiences. You can choose a lifetime of bliss. In other words, you can choose a lifetime of maximum pleasure. Once inside you won't know that you are inside the experience machine, “you'll think that it's all actually happening”. (Nozick, 1974.) 3. The Experience Machine ● ● If hedonism is true, then it should follow that it's better to be inside the machine than not, and that there's nothing of value (noninstrumental) unavailable to a person inside the machine. (Shafer-Landau: 2009) It's taken to be intuitive that choosing a life inside the machine would be a mistake. 3. The Experience Machine ● Implications, if that intuition is correct: – How one's life feels from the inside is not the sole determinant of how well one's life has gone. – A life of maximum pleasure and minimum pain inside the experience machine would not be a maximally good life. 3. The Experience Machine ● ● ● What matters to us in addition to our experiences? Nozick's response: – We want to do certain things – We want to be a certain way – Not being limited to a man-made reality But, as Nozick notes, the first two could also be brought about by a similar types of machines. 3. The Experience Machine Nozick's diagnosis ● ● What is disturbing about such machines is their living our lives for us. Nozick suggests that we want to live in contact with reality. 3. The Experience Machine ● ● A hedonist might respond by arguing that our intuitions in response to the experience machine thought experiment our misleading. (Crisp, 2013). Another possible hedonist response is to say that pleasure deservedly had is more valuable and that pleasure derived from the experience machine is not appropriately derived. For more, see Feldman (2002). 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory ● One response to the experience machine thought experiment might be to say that what matters is that we have our desires fulfilled. – In other words, it seems more likely that people would desire to actually write a great novel rather than just have the experience of doing so. 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory ● On one version of desire-fulfilment theory “what matters to a person's well-being is the overall level of desire satisfaction in their life as a whole”. (Crisp, 2013). 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory ● ● Something is good for someone if and only if it fulfils their desires in their life as a whole. The implications – This means that the fulfilment of any such desires will be good for a person. – And that anything that is not the satisfaction of such a desire cannot be good for a person 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory The Orphan Monk Case ● ● At a very early age a young man began training to become a monk. As a result he has led a very sheltered life. He is offered a choice of continuing to be a monk or becoming a cook or a gardener. He has no conception of what it would be like to be a cook or a gardener so he chooses (and desires) to remain a monk. (Crisp, 2013.) – Yet it seems possible that he might live a better life if he choose one of the other two options. 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory ● ● One attempted response is to build into a desire fulfilment account that the relevant agent desires contribute toward the good life if and only if those desires are informed. This version of the theory faces a challenging case articulated by John Rawls (in Crisp, 2013). – “Imagine a brilliant Harvard mathematician, fully informed about the options available to her, who develops an overriding desire to count blades of grass on the lawns of Harvard.” 4. Desire-Fulfilment Theory Response ● ● The desire-fulfilment theorist might insist that, if the mathematician lives a life in which her desires are fulfilled, even if that includes counting blades of grass, then that's all that matters. Counterexamples to hedonism and desire fulfilment theory: – something beyond a subject's experiential states or whether she satisfies her desires may contribute to how well her life has gone for her. 5. Objective List Theory ● ● Aristotle: We should desire things because they’re good, not think things are good because we desire them. According to this theory there are a number of goods, possibly including knowledge and friendship, which contribute towards the good life. – Note, the list may also include pleasure. 5. Objective List Theory ● ● Certain things are good or bad for us, whether or not we want to have the good things, or to avoid the bad things But what things are they? How do we go about finding out what they are? 5. Objective List Theory ● ● An objective list approach leaves so open what could contribute to the good life that can yield the right answer in a multitude of cases, but fails as a theory in providing specifics as to what should be included. But this objection is somewhat unfair. – Various philosophers have been developing objective list theory in various directions. (e.g. the perfectionist approach of Thomas Hurka, 1993). 6. Conclusion ● ● Objections to hedonism suggest: – Not all pleasure is good for us – Pleasure isn't the only thing that's good for us Objections to desire-fulfillment theory suggest: – Fulfilling our desires is not the only thing that is good for us – The fulfillment of some desires may be not be good for us. 6. Conclusion ● Objective list theory looks like providing the most promising answer. – But is this just because in an under-developed form we can imagine it satisfying all our intuitions to the various cases? – How should we go about determining what should be included on any list? – Are the goods that we might identify in any way connected?