Caecal evisceration following stab wound

advertisement

Appendicitis & Peritonitis Dr. Belal Hijji, RN, PhD April 25 & 27, 2011 Learning Outcomes At the end of this lecture, students will be able to: • Describe the appendix and appendicitis along with its pathophysiology. • Identify the clinical manifestations of appendicitis. • Discuss assessment and diagnostic findings of appendicitis. • Describe the medical and nursing care of a patient with appendicitis. • Define peritonitis, its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and its diagnosis. • Discuss the complications, and medical and nursing management of peritonitis. 2 Appendix 3 Appendicitis • The appendix is a small, finger-like tube about 10 cm (4 in) long that is attached to the cecum just below the ileocecal valve. The appendix fills with food and empties regularly into the cecum. Because it empties inefficiently and its lumen is small, the appendix is prone to obstruction and is particularly vulnerable to infection (ie, appendicitis). 4 Pathophysiology • The appendix becomes inflamed and edematous as a result of either becoming kinked or occluded by a fecalith (ie, hardened mass of stool), tumor, or foreign body. The inflammatory process increases intraluminal pressure, initiating a progressively severe, generalized or upper abdominal pain that becomes localized in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen within a few hours. 5 Clinical Manifestations • Epigastric or periumbilical pain progresses to the right lower quadrant. • Low-grade fever, nausea and sometimes vomiting. Loss of appetite. • Local tenderness is elicited at McBurney’s point when pressure is applied (next 2 slides). • Rebound tenderness (ie, production or intensification of pain when pressure is released) may be present. • Rovsing’s sign may be elicited by palpating the left lower quadrant; this causes pain to be felt in the right lower quadrant. • If the appendix has ruptured, the pain becomes more diffuse; abdominal distention develops, and the patient’s condition worsens. 6 Location of McBurney's point (1), located two thirds the distance from the umbilicus (2) to the anterior superior iliac spine (3). 7 8 Assessment and Diagnostic Findings • Health history and physical exam. • Complete blood cell count demonstrates an elevated white blood cell count (> 10,000 cells/mm3). The neutrophil count may exceed 75%. • Abdominal x-ray films, ultrasound studies, and CT scans may reveal a right lower quadrant density or localized distention of the bowel. 9 Medical Management • Surgical intervention (appendectomy), next slide, as soon as possible after diagnosis to decrease the risk of perforation. • Before surgery, correction or prevention of fluid and electrolyte imbalance and dehydration could be through antibiotics and intravenous fluids. • Analgesics can be administered after the diagnosis is made. 10 An appendectomy in progress 11 Nursing Management • Prepare the patient for surgery, which includes an intravenous infusion to replace fluid loss and promote adequate renal function and antibiotic therapy to prevent infection. • Post-operatively, Place the patient in a semi-Fowler position to reduce the tension on the incision and, thus, reduce pain. • Administer pain killers (usually morphine sulfate), as prescribed. • Start oral fluids when tolerated and intravenous fluids as indicated. Food is provided as desired and tolerated on the day of surgery. 12 Nursing Management (Continued…..) • Instruct the patient to make an appointment to have the surgeon remove the sutures between the fifth and seventh days after surgery. • Teach incision care (dressing) and activity guidelines; normal activity can usually be resumed within 2 to 4 weeks. 13 Peritonitis • Peritonitis is inflammation of the peritoneum, the serous membrane lining the abdominal cavity and covering the viscera. • It results from bacterial infection; the organisms come from diseases of the GI tract or, in women, from the internal reproductive organs. • Peritonitis can also result from injury or trauma (eg, gunshot wound, stab wound). • The most common bacteria implicated are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, and Pseudomonas. • Peritonitis may also be associated with abdominal surgical procedures and peritoneal dialysis. 14 Autopsy of infant showing abdominal distension, intestinal necrosis and hemorrhage, and peritonitis due to perforation . 15 Pathophysiology • Peritonitis is caused by leakage of contents from abdominal organs into the abdominal cavity due to inflammation, infection, ischemia, trauma, or tumor perforation. • Edema of the tissues results, and exudation of fluid develops in a short time. Fluid in the peritoneal cavity becomes turbid with increasing amounts of protein, white blood cells, cellular debris, and blood. • The immediate response of the intestinal tract is hypermotility, followed by paralytic ileus with an accumulation of air and fluid in the bowel. 16 Clinical Manifestations • Diffuse abdominal pain is felt. The pain tends to become constant, localized, and more intense near the site of the inflammation. • Movement usually aggravates pain. • The affected area becomes extremely tender and distended, and the muscles become rigid. • Usually, nausea and vomiting occur and peristalsis is diminished. • Fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis. 17 Assessment and Diagnostic Findings • Leukocytosis. • The hemoglobin and hematocrit levels may be low if blood loss has occurred. • An abdominal x-ray shows air, fluid levels, and distended bowel loops. • An abdominal Computerised Tomography (CT) scan may show abscess formation. • Peritoneal aspiration and culture and sensitivity studies of the aspirated. 18 Complications • Generalized sepsis, frequently, affects the whole abdominal cavity. • Sepsis is the major cause of death from peritonitis. • Shock may result from septicemia or hypovolemia. • The inflammatory process may cause intestinal obstruction, primarily from the development of bowel adhesions. • The two most common postoperative complications are wound evisceration (next slide) and abscess formation. Any suggestion from the patient that an area of the abdomen is tender or painful must be reported. 19 Caecal evisceration following stab wound 20 Medical Management • Fluid, colloid (blood, plasma) , and electrolyte replacement. Hypovolemia occurs because of massive loss of fluid and electrolytes. • Analgesics for pain; antiemetics for nausea and vomiting. Intestinal intubation and suction to relieve abdominal distention. • Fluids in the abdominal cavity can affect lung expansion and causes respiratory distress. Oxygen therapy is indicated with or without airway intubation and ventilatory assistance. • Massive antibiotic therapy. • Surgical objectives include removing the infected material and correcting the cause. Surgical treatment is directed toward excision (ie, appendix), resection with or without anastomosis (ie, intestine), repair (ie, perforation), and drainage (ie, abscess). 21 Nursing Management • Ongoing assessment of pain, vital signs, GI function. • The nurse reports the nature of the pain, its location in the abdomen, and any shifts in location. • Administering analgesic medication and positioning the patient for comfort. The patient is placed on the side with knees flexed; this position decreases tension on the abdominal organs. • Accurate recording of all intake and output and central venous pressure assists in calculating fluid replacement. • The nurse administers and monitors closely intravenous fluids. 22

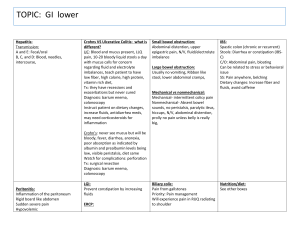

![Lymphatic problems in Noonan syndrome Q[...]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006913457_1-60bd539d3597312e3d11abf0a582d069-300x300.png)