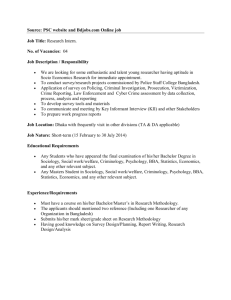

Bangladesh has the potential to attract significantly higher levels of

advertisement