CAD in Women by Dr Sarma

advertisement

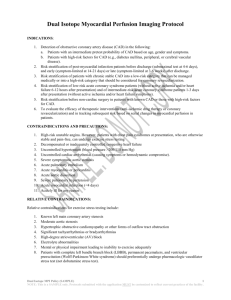

1 Women and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) What do we need to know ? Dr. R.V.S.N.Sarma, M.D., M.Sc., (Canada) Consultant Physician and Chest Specialist Thiruvallur, Chennai 2 3 4 5 6 Myths vs Facts Myths Facts Men are more likely to have heart disease Heart disease is the #1 killer of men and women; 50,000 more women than men die of heart disease every year Cancer is a bigger threat than heart disease Nearly twice as many US women die from heart disease and stroke than from all cancers combined Doctors are aware of women’s risk for heart disease and act accordingly Undertreatment and underdiagnosis of heart disease in women contributes to excess mortality in women 7 Women’s Perceptions of Heart Disease • 72% of young women (ages 25-40) still consider cancer to be the greatest threat to women’s health • Some women know about the risks of heart disease but do not hear it from their own doctors and do not “personalize” it • 65% of women recognize that symptoms may be “atypical” but do not know classic symptoms • Most women learn about coronary artery disease (CAD) from magazines and the Web—not from their own physicians! Robinson A. Circulation. 2001 8 Gender Bias in the Treatment of Women “… The community has viewed women’s health almost with a ‘bikini’ approach, looking essentially at the breast and reproductive system, and almost ignoring the rest of the woman as part of women’s health ….” Nanette Wenger, MD Chief of Cardiology, Grady Hospital Professor of Medicine, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia 9 Magnitude of the Problem • 2.5 million women per year in the US are hospitalized with cardiovascular disease (CVD) • Deaths from CVD = 500,000/yr • Leading cause of death in US women: CAD • >230,000 women die from CAD each year • 1990: US Congress directed the National Institutes of Health that women be included in clinical trials and that gender differences be evaluated 10 Women in Clinical Trials • Women are underrepresented in cardiovascular (CV) trials – Evidence-based CV medicine biased toward men • Food and Drug Administration/National Institutes of Health mandate: 50% enrollment of women • Women need to be empowered to enroll in clinical trials for heart disease – Breast-cancer awareness is a good example 11 Publication Bias: Gender Representation and Negative Studies • 1966-1994 noninvasive testing literature – 8% to 27% women • Lower diagnostic accuracy in women – High false-positive rates – Inability to perform maximal stress 12 Deaths in Thousands CVD Mortality Trends (1979-1999) American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. 2001 13 Percent of Population Prevalence of CVD in the US 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 79.00 70.7 Males Females 65.2 65.20 51.0 48.10 34.2 28.90 10.4 5.5 4.60 4.20 20-24 25-34 17.4 13.60 35-44 45-54 Ages 55-64 65-74 75+ American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. 2001 14 Deaths in Thousands Deaths From CVD and Cancer by Age and Sex 300,000 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 <45 45-64 65-84 >84 Ages CVD: Males Cancer: Males CVD: Females Cancer: Females Anderson RN. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2002 15 Deaths From CVD (1999) Congenital cardiovascular Rheumatic fever/rheumatic defects 0.5% heart disease 0.4% Diseases of the arteries 2.0% High blood pressure 5.0% Other 14.9% Coronary heart disease 54.5% Congestive heart failure 5.9% Stroke 16.8% American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. 2001 16 Health Threats to Women: Perception vs Reality 1 Perceived health threats Leading causes of death in women 55% 2 46% 40% 24% 22% ts 3% Ac ci de n eu m on i PD Pn C O ce r C an C AD ta ck rt H ea di rt at se as e r H ea Br ea st ca nc e ce r C an 4% a 4% 2% 1. Gallup survey. 1995 2. American Heart Association. Heart & Stroke Facts. 1996 Statistical Supplement 17 Death From Breast Cancer or Heart Disease in Women in the US US Vital Statistics, 1990 18 Statistics for Women • 503,927 died of CVD in 1998 – 226,467 from heart attack or other cardiac events – 97,303 from stroke • 1 in 5 women has some form of CVD • 38% of women who have a heart attack die within 1 year • 40% of coronary events in women are fatal – Most occur without prior warning 19 Women and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) Risk Factors and Gender Differences 20 Warning Signs and Symptoms of CAD 21 Gender Differences in Heart Attack Symptoms Typical in both sexes Typical in women • Pain, pressure, squeezing, or stabbing pain in the chest • Pain radiating to neck, shoulder, back, arm, or jaw • Pounding heart, change in rhythm • Difficulty breathing • Heartburn, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain • Cold sweats or clammy skin • Dizziness • Milder symptoms (without chest pain) • Sudden onset of weakness, shortness of breath, fatigue, body aches, or overall feeling of illness (without chest pain) • Unusual feeling or mild discomfort in the back, chest, arm, neck, or jaw (without chest pain) 22 Less Common Heart Attack Symptoms in Women • Milder symptoms without accompanying chest pain • Sudden onset of weakness, shortness of breath, fatigue, body aches, overall feeling of illness • Burning sensation in the chest, may be mistaken as heartburn • An “unusual” feeling or mild discomfort in the back, chest, arm, neck, or jaw 23 Major Risk Factors for Heart Disease Modifiable Nonmodifiable Emerging Risk Factors High blood pressure Family history Homocysteine Abnormal cholesterol levels Age Elevated lipoprotein (a) levels Diabetes Gender Clotting factors Cigarette smoking Markers of inflammation (CRP) Obesity Physical inactivity Grundy SM, et al. Circulation. 1998; Grundy SM. Circulation. 1999 Braunwald E. N Engl J Med. 1997; Grundy SM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 24 Emerging Risk Factors • • • • • • Lipoprotein (a) Homocysteine Prothrombotic factors Proinflammatory factors Impaired fasting glucose Subclinical atherosclerosis – Other clinical forms of atherosclerotic disease (peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and symptomatic carotid artery disease) – Abnormal internal or common carotid CIT, ankle-arm index <0.9, coronary Ca2+ 25 Diabetes Creates Higher Risks for Women With CAD • 65% of diabetics die from heart disease or stroke • 4.2 million American women have diabetes – Diabetes increases CAD risk 3-fold to 7-fold in women vs 2fold to 3-fold in men – Diabetes doubles the risk of second heart attack in women but not in men • Every year, heart disease kills 50,000 more American women than men • Statistics are particularly high among African American women American Heart Association Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Manson JE, et al. Prevention of Myocardial Infarction. 1996 26 Lowest Survival Rates for Diabetic Women • CAD mortality rates in diabetics, especially women, have not decreased to the same extent as those in the general population • In a large cohort referred for coronary disease, diabetic women had the highest mortality rates – Estimate of ischemic burden with stress myocardial perfusion imaging significantly improved risk stratification in diabetic women compared with clinical risk alone – Stratification by the number of ischemic vessels demonstrated a significant linear increase in cardiac events with escalating ischemic burden (sex-diabetes interaction, P = .016) Gu K, et al. JAMA. 1999 Giri S, et al. Circulation. 2002 27 Diabetes: Powerful Risk Factor for CAD in Women • Framingham Heart Study – Women with diabetes mellitus had relative risk of 5.4% for CAD vs women without diabetes – Men with diabetes had relative risk of 2.4% • Nurses’ Health Study – Relative risk of 6.3% for total cardiovascular (CV) mortality – Even if women had diabetes for <4 years, their risk of CAD was significantly elevated Kannel W. Am Heart J. 1987 Manson J, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1991 28 Clinical Identification of the Metabolic Syndrome • Abdominal obesity – Men – Women • Triglycerides (TG) • HDL cholesterol – Women – Men • Blood pressure • Fasting glucose >88 cm (>40 in) >80 cm (>35 in) >150 mg/dL <50 mg/dL <40 mg/dL >130/>85 mm Hg >100 mg/dL National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 29 Impact of Triglyceride Levels on Relative Risk of CAD Framingham Heart Study Relative Risk (x-fold) 2.5 2.2 Women Men 2 1.85 1.8 1.45 1.4 1.5 1.2 1 1 0.55 0.65 2.15 1.3 1.25 1.25 300 350 400 1 0.8 0.75 100 150 0.5 0 50 200 250 Castelli WP. Can J Cardiol. 1988 30 Women and CAD Risk Factors • Higher prevalence of avoidable risk factors1 – ↑ blood cholesterol, ↑ TG – ↑ physical inactivity – ↑ overweight (body mass index, 25.0-29.9) • Diabetes is a more powerful risk factor for CAD2 – 3- to 7-fold in women vs 2- to 3-fold in men • ↓ HDL cholesterol levels more predictive of CAD2 • Women counseled less about nutrition, exercise, and weight control2 1. American Heart Association. 1999 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. 1998 2. Mosca L, et al. Circulation. 1999 31 MI or Death Often First Sign of CAD Percentage of patients whose first CAD diagnosis is MI or death 62% 46% Men Women Levy D, et al. Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 1998 32 Smoking • Single most preventable cause of death in US • Smoking by women causes 150% more deaths from heart disease than lung cancer • Women who smoke are 2-6 times more likely to suffer a heart attack • Use of birth control pills in smokers compounds cardiac risk 33 Overweight Percent of population Prevalence of Overweight in Americans Aged 20-74 Years 70 60 50 40 30 20 49 55 61 53 51 40 41 42 10 0 Men 1960-1962 Women 1971-1974 1976-1980 1988-1994 American Heart Association. 2002 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update. 2001 34 Physical Inactivity • Lack of exercise is a proven risk factor for heart disease – A lack of regular physical exercise is a growing epidemic all over the world. “We seem to eat much more than what we burn” • Heart disease is twice as likely to develop in inactive people than in those who are more active • Physical activity helps maintain weight, blood pressure, and diabetes • Women should exercise to increase heart rate for 20-30 minutes a day, 3-5 times per week 35 Hormonal Effects on Ischemia and Disease Prevalence • Premenopause – Estrogen has digoxin-like effect: ST • Post-menopause effect on HRT – ST - vasodilatory effects of HRT – Increase exercise duration/decrease chest pain • Women with intact uterus take progestin to protect against uterine malignancies – Estrogen and medroxyprogesterone attenuate this effect Lloyd GW, et al. Heart. 2000; Webb CM, et al. Lancet. 1998; Morise AP, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1993; Rosano GM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 36 Hormonal Effects on Ischemia and Disease Prevalence • Estrogen modulates chest pain syndromes • Premenopausal CAD: angina/ischemia variation by menstrual cycle – Early follicular phase estradiol and progesterone levels - low < time to ischemia onset – Mid-cycle estrogen levels - highest > time to ischemia onset Lloyd GW, et al. Heart. 2000; Webb CM, et al. Lancet. 1998; Morise AP, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1993; Rosano GM, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000 37 Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Cardioprotection • First randomized trial • HERS trial (Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study) – Secondary CAD prevention trial – Randomized trial of placebo vs estrogen and medroxyprogesterone – Follow-up = 4 years – N = 2,763 women with an intact uterus – Outcome measures • Primary: nonfatal MI or cardiac death • Secondary: unstable angina, coronary revascularization, congestive heart failure HERS trial. JAMA. 1998. 38 Is There a Role for HRT? • Secondary prevention – 1998: HERS • 4 years of treatment with conjugated estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone acetate • No reduction in the risk of MI and coronary death in women with established CAD HERS trial. JAMA. 1998. 39 Is There a Role for HRT? • Secondary prevention – 3/2000: Estrogen Replacement and Atherosclerosis trial (ERA) • 309 postmenopausal women with CAD • Placebo vs conjugated estrogen (.625 mg/day) vs conjugated estrogen (.625 mg/day) with medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg/day) • Angiographic analysis of the diameter of the coronary arteries at the start of the study and 3 years later • ERA trial results at follow-up angiography – The progression of coronary atherosclerosis was unchanged in the women randomized to either of the estrogen groups ERA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 40 Is There A Role for HRT? • Primary prevention – Women’s Health Initiative. WHI trial • 160,000 women:1991-2005 • Initial results: no cardioprotection attributed to HRT in women on HRT • American Heart Association: HRT not recommended for primary or secondary cardioprotection 41 Conclusions: Risk Factor Management • CVD begins in childhood and is strongly associated with major risk factors for heart disease • Multiple risk factors require more aggressive management • Aggressive risk-factor modification (often with multiple medications) is the most effective strategy for reducing the consequences of heart disease Berenson GS, et al. N Engl J Med. 1998. Neaton JD, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1992. Kannel WB. in Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease. 1996. Grundy SM, et al. Circulation. 1999 42 Gender Differences in CAD Risk Factors • Increasing recognition that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory process • Ridker PM, et al: A prospective casecontrolled study among 28,263 postmenopausal women – Among 12 markers of inflammation, C reactive protein was the strongest univariate predictor of the risk of CV events Ridker PM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2000 43 Women and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) Diagnosis and Prognosis 44 Diagnosis and Management of CAD in Women • Gender differences: presentation, manifestation, and diagnosis of CAD • Gender differences in mortality – 63% of women who die suddenly from CAD had no prior warning symptoms – 42% of women vs 24% of men will die within 1 year after MI • Thus, early recognition of symptoms and accurate diagnosis of CAD is of great importance 45 Heart Disease in Women: Lessons From the Past Decade • The importance of studying gender-specific aspects of CAD have helped in the following clinical dilemmas: – At Presentation of CAD: women are older than men – Less specific clinical manifestations of CAD in women – Greater difficulty in diagnosis: women > men – More severe consequences on MI when it occurs in women 46 Screening for Heart Disease What Tests Should we use to identify Coronary Heart Disease? 47 Limited Representation of Women in Studies of CAD Testing Women 92 100 Percent of patients Men 78 80 73 60 40 20 22 27 8 0 ECG Echo MPI Adapted from: Shaw LJ, et al. Coronary Artery Disease in Women: What All Physicians Need to Know. 1999 48 Are There Gender Differences in Noninvasive Diagnostic Tests? Is There a Difference in Diagnostic Accuracy of Noninvasive Tests? 49 Noninvasive Testing Options Stress ECG Stress Echo Stress MPI EBCT PET MRI 50 Noninvasive Testing in Symptomatic Women • Stress electrocardiography (ECG) • Stress echocardiography (ECHO) • Stress nuclear imaging (MPI) 51 Exercise ECG (Treadmill) • Despite advances in technology, the exercise ECG remains an important tool in the diagnosis and prognosis of the patient suspected of having CAD • The exercise ECG has an overall sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 77% for the detection of CAD in men • The sensitivity and specificity of the exercise ECG in women are about 61% and 70% respectively Kwok Y, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1999. 52 ECG Testing in Women Sensitivity and Specificity Study, Year Detry et al, 1977 Weiner et al, 1979 Barolsky et al, 1979 Friedman et al, 1982 Guiteras et al, 1982 Hung et al, 1984 No. of Women 47 580 92 60 112 92 Sensitivity (%) Specificity (%) 80 76 60 32 79 73 63 64 68 41 66 59 Adapted from Heller GV, et al. Nuclear Cardiology: State of the Art and Future Directions. 1998 53 Gender Differences in Exercise ECG Testing • sensitivity in women >65 years • specificity in women on hormone replacement therapy • false-positive results due to autonomic/hormonal influences • Digoxin like effect of estrogen Shaw LJ, et al. CAD in Women: What All Physicians Need to Know. 1999 54 Diagnosis of Noninvasive Tests in Women • • • • • ECG Nuclear perfusion study ECHO – poor window problem Dipyridamole injection – MPI, Stress (Tread mill) Echo – – Dobutamine infusion Echo – • Computed tomography • MR coronary angiography 55 Nuclear Imaging in Women • Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) • Large body of evidence in women – Gender-specific data available for Tl-201and Tc-99m tracers – Tc-99m tracers = agent of choice for women due to decrease attenuation artifacts from breast tissue – Gated single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) provides post stress ejection fraction and regional wall motion helpful to reduce false positives – IV adenosine/dipyridamole stress provides comparable overall accuracy in women and men 56 Comparative Test Statistics on Diagnostic Accuracy in Women ECG (n = 3721) Echo (n = 296) Nuclear (Tl-201) (n = 842) Nuclear (Gated tech) (n = 100) Sensitivity Specificity 61% 86% 78% 84% 70% 79% 64% 94% Kwok Y, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1999 57 Diagnostic Specificity: Stress Thallium Tl-201 vs Tc-99m Sestamibi 92% N = 115, P = .0004 • Perfusion imaging – Regional blood flow • Robust evidence in women 21 false + 10 false + 67% Tl-201 Tc-99m sestamibi – Gender-specific data for Tl201 and Tc-99m sestamibi or teboroxime – Tc-99m sestamibi is agent of choice for women (reduced breast attenuation) • Gated SPECT – Post-stress EF and regional wall motion – Reduce false-positive tests • Pharmacologic stress helpful in older and obese women Hachamovitch R. et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996; Amanullah AM, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1997; Taillefer R, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 58 Pharmacologic Stress Testing in a Community Setting: Women vs Men Percent of patients referred for MPI who underwent exercise stress vs pharmacologic stress at Mission Internal Medicine Group, Mission Viejo, CA (4/21/02 to 8/29/02) Women (n = 243) Men (n = 375) Pharmacologic 34% Pharmacologic 53% Exercise 47% Exercise 66% Data provided by Greg Thomas, MD, Mission Internal Medicine Group 59 ECHO Testing in Women • Overall – Convenient/readily available1,2 – Avoids ionizing radiation2 – Identifies cardiac structure and left ventricular function (LVF) • Sensitivity and specificity vs ECG testing1,2 – Increased sensitivity (79%-88%) – Increased specificity (77%-86%) 1. Williams MJ, et al. Am J Cardiol. 1994 2. Marwick T, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 60 PET Imaging for CAD in Women Positron Emission Tomography 61 PET Case Study: Patient FF Stress Rest 62 PET Case Study: Patient FF Ischemia of Lateral Wall 63 Electron Beam Computed Tomography (EBCT) • Resting study only • Stationary tungsten target permits rapid scanning • Detects coronary calcification • Abnormality defined as presence of any calcium Courtesy of Howard Lewin, MD, of San Vicente Cardiac Imaging Center Diagnostic Accuracy of EBCT Coronary Calcium Scores by Gender Subsets 64 100 90 88 88 80 69 Percentage 70 61 60 49 50 48 40 30 20 10 0 Sensitivity Specificity Women Sensitivity Specificity Men Predictive accuracy Predictive accuracy Women Men Devries S, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995. Rumberger JA, et al. Circulation. 1995. Detrano R, et al. Am J Card Imaging. 1996. 65 Technetium-99m SPECT Imaging Predicts Cardiac Mortality in Women Ischemia extent and survival by number of vascular territories Cardiac survival 1.0 0 1 2 0.9 1.0 0 98.5% 1 2 0.9 3 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.8 Women (n = 3402) 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 Years 80-87% 0.7 3 Men (n = 4500) 0.6 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 Years 2.5 3 Marwick TH, et al. Am J Med. 1999 hs-CRP, Lipids, and Risk of Future Coronary Events: Women's Health Study (WHS) 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 4 Quartile of TC: HDL-C 3 2 1 Ridker PM et al. N Engl J Med 2000;342:836-843. 1 2 3 4 Quartile of hs-CRP Risk Factors for Future Cardiovascular Events: WHS Lipoprotein(a) Homocysteine IL-6 TC LDL-C sICAM-1 SAA Apo B TC:HDL-C hs-CRP hs-CRP + TC:HDL-C 0 1.0 2.0 4.0 6.0 Relative Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events Ridker PM et al. N Engl J Med 2000;342:836-843. Women’s Health Initiative: Trial of Estrogen plus Progestin 16,608 women randomized Conjugated equine estrogens 0.625 mg/d + medroxyprogesterone acetate 2.5 mg/d vs. placebo Primary outcome: nonfatal MI or CHD death Primary adverse outcome: breast cancer Stopped early (mean follow-up 5.2 years) because health risks exceeded benefits Writing Group for the WHI Investigators. JAMA 2002;288:321-333. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen/Progestin on Clinical Outcomes: Women’s Health Initiative Hazard Ratio Nominal 95% CI Adjusted 95% CI CHD (MI, coronary death) 1.29 1.02–1.63 0.85–1.97 CABG/PTCA 1.04 0.84–1.28 0.71–1.51 Stroke 1.41 1.07–1.85 0.86–2.31 Venous thromboembolic disease 2.11 1.58–2.82 1.26–3.55 Total CVD 1.22 1.09–1.36 1.00–1.49 Cancer 1.03 0.90–1.17 0.86–1.22 Fractures 0.76 0.69–0.85 0.63–0.92 Death 0.98 0.82–1.18 0.70–1.37 Global index* 1.15 1.03–1.28 0.95–1.39 Outcome Absolute Excess Risks and Absolute Risk Reductions per 10,000 PersonYears: Women’s Health Initiative Difference in risk per 10,000 person-years CHD events +7 Strokes +8 Pulmonary embolisms +8 Invasive breast cancer +8 Colorectal cancers –6 Hip fractures –5 Global index +19 Writing Group for the WHI Investigators. JAMA 2002;288:321-333. 71 Treatment differences • Thrombolysis – equally effective – Cerebral hemorrhage risk is more • Low rates of coronary angiography in women • Under referral for revascularization procedures • CABG - > operative mortality 1.9 % v/s 4.6% • Restenosis after PTCA, or CABG occlusion rates are more for women - ? Smaller lumen sizes 72 Summary • • • • • • • • Presentation and symptomatology Cardiac risk factors – differences Metabolic syndrome, Obesity – IR – DMII Dyslipidemia patterns TMT – lower value Stress Echo, MPI, Sistemibi, Dobuatamine CABG, PTCA risks, long term Above all need for greater clinical suspicion 73 Take-Home Messages • The majority of risk factors for CAD can be improved by lifestyle modification. • Goals for “optimal” levels continue to decrease with each new guideline version. • The gap between “average” and “optimal” will continue to widen unless lifestyle modification is adopted more successfully. 74 Take-Home Messages • Diet, exercise (attaining ideal body weight), and smoking cessation are key lifestyle changes. – No “quick-fix” – Extreme changes are usually not sustainable – Medications are not an antidote to an unhealthy lifestyle 75 Take-Home Messages • Work with your patient to set realistic goals. • Remember that modest changes in diet, weight, and exercise can have a big impact on cardiac risk. • A heart-healthy lifestyle should be encouraged from youth, but even changes later in life lead to important benefits.