Stroke

advertisement

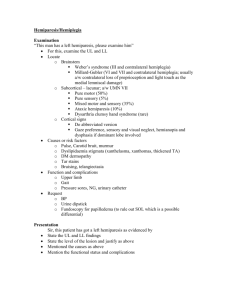

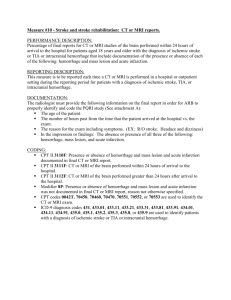

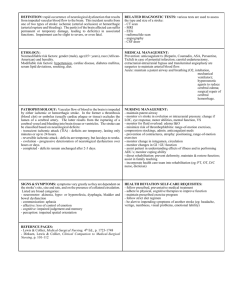

‘Stroke’ Cerebrovascular diseases Vascular diseases of the nervous system are amongst the most frequent causes of admission to hospital. Strokes of all types rank third as a cause of death, surpassed only by heart disease and cancer. The annual incidence in the UK varies between 150-200/100 000, with a prevalence of 600/100 000 of which one third are severely disabled. Risk factors Prevention of cerebrovascular disease is more likely to reduce death and disability than any medical or surgical advance in management. Prevention depends upon the identification of risk factors and their correction. Hypertension (a major factor, no critical BP level). Cardiac disease (cardiac enlargement, failure, arryhthmias, rheumatic heart disease, patent foramen ovale) Diabetes (the risk of cerebral infarction is increased twice). Heredity Blood lipids, cholesterol, smoking, diet/obesity Haematocrit (a Hb concentration, fibrinolysis) Oral contraceptives ? Cerebrovascular diseases mechanisms ‘Stroke’ is a generic term, lacking pathological meaning. Cerebrovascular diseases can be defined as those in which brain disease occurs secondary to a pathological disorder of blood vessels (usually arteries) or blood supply. Whatever mechanism, the resultant effect on the brain is either: ischemia/infarction, or haemorrhagic disruption Of all strokes: - 85% are due to INFARCTION - 15% are due to HAEMORRHAGE Cerebrovascular diseases – natural history Approximately 1/3 of all ‘strokes’ are fatal. The age of the patient, the anatomical size of the lesion, the degree of deficit and the underlying cause all influence the outcome. In cerebral haemorrhage, mortality approaches 50%. Cerebral infarction fares better, with an immediate mortality of less than 20%, fatal lesions being large with associated oedema and brain shift. Embolic infarction carries a better outcome than thrombotic infarction. The level of consciousnees on admission to hospital gives a good indication to immediate outcome. The deeper the conscious level the graver the prognosis. Cerebrovascular diseases – causes Occlusion (50%) Atheromatous/thrombotic 1. Large vessel occlusion or stenosis (e.g. carotid artery) 2. Branch vessel occlusion or stenosis (e.g. MCA) 3. Perforating vessel occlusion (lacunar infarction) Non-atheromatous diseases of the vessel wall 1. Collagen disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosis) 2. Vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa) 3. Granulomatous vasculitis (e.g. Wegener’s granulomatosis) 4. Miscellaneous (e.g. syphilitic vasculitis, sarcoidosis, …) Embolisation (25%) mostly from atheromatous plaque in the intracranial or extracranial arteries or from the heart. Haemorrhage (20%); parenchymal (15%), SAH (5%) Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) = episodes of focal neurological symptoms due to inadequate blood supply to the brain. Attacks are sudden in onset, resolve within 24 hours or less and have no residual deficit. These attacks are important as warning episodes or precursors of cerebral infarction. The pathogenesis: A reduction of cerebral blood flow below 20-30 ml/100 g/min produces neurological symptoms. The development of infarction is a consequence of the degree of reduced flow and the duration of such a reduction. If flow is restored within the critical period, ischemic symptoms will reverse. Emboli are accepted as the cause of the majority of TIAs. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery The degree of deficit varies – it may be asymptomatic or a catastrophic infarction may result. In the most extreme cases there may be: Unconsciousness, contralateral hemiplegia, contralateral hemisensory disturbance, homonymous hemianopia of the contralateral side and gaze palsy to the opposite side (eyes are deviated to the side of the lesion!). Occlusion of the dominant hemisphere side will result in a global aphasia. Prodromal symptoms prior to occlusion may take the form of monocular blindness – AMAUROSIS FUGAX and transient hemisensory or hemimotor disturbance. Branch vessel occlusions or stenosis Occlusion of the anterior cerebral artery Cortical branches supply the medial surface of the hemisphere: Orbital, frontal, and parietal ctx. Deep branches pass to the anterior part of the internal capsule and basal nuclei. Clinical features depend on the site of occlusion (especially in relation to the anterior communicating artery) and anatomical variation. Occlusion proximal to the AComA is normally well tolerated because of the cross flow. Distal occlusion results in weakness and cortical sensory loss in the contralateral lower limb with associated incontinence. Bilateral frontal lobe infarction may result in akinetic mutism or deterioration in conscious level. Occlusion of the middle cerebral artery MCA is the largest branch of the ICA. It gives off deep branches (perforating arteries) which supply the anterior limb of the internal capsule and part of the basal nuclei. It then passes out to the lateral surface of the hemisphere and here it gives off cortical branches temporal, frontal, and parietal. Clinical features depend on the site of occlusion and whether dominant or non-dominant hemisphere is affected. All cortical branches are involved – contralateral hemiplegia (leg relatively spared), contralateral hemianaesthesia and hemianopia, aphasia (dominant), neglect syndrome (non-dominant hemisphere). Vertebral artery occlusion The vertebral artery arises from the subclavian artery on each side. Underdevelopment of one vessel occurs in 10%. VA and its branches supply the medulla and the inferior surface of the cerebellum before forming the basilar artery. Clinical features variable. When low in the neck, it is compensated by anastomotic channels. When one VA is hypoplastic, occlusion of the other is equivalent to basilar artery occlusion. Typical VA occlusion presents as a PICA syndrome: dysarthria, ipsilateral limb ataxia, vertigo and nystagmus, contralateral sensory loss (pain/temperature) of limbs and trunk, ipsilateral sensory loss (pain/temp.) of face, ipsilateral pharyngeal and laryngeal paralysis. Basilar artery occlusion The basilar artery supplies the brainstem from medulla upwards and divides eventually into posterior cerebral arteries which run forward to join the anterior circulation (circle of Willis). Clinical features: Prodromal symptoms are common and may take the form of diplopia, visual field loss, intermitent memory disturbance and a whole constellation of other brainstem symptoms: vertigo, ataxia, paresis, paraesthesia. The complete basilar syndrome following occlusion consists of: Coma, bilateral motor and sensory dysfunction, cerebellar signs and cranial nerve signs. Very serious condition! Lacunar stroke Occlusion of deep penetrating arteries produces subcortical infarction characterised by preservation of cortical function – language, other cognitive and visual functions. Clinical syndromes are distinctive and normally result from long-standing hypertension. In 80%, infarcts occur in periventricular white matter and basal ganglia, the rest in cerebellum and brainstem. Areas of infarction are 0.5-1.5 cm in diameter and occluded vessels demonstrate lipohyalinosis, microaneurysms and microatheromatous changes. Lacunar or subcortical infarction accounts for 17% of all thromboembolic strokes and knowledge of commoner syndromes is essential. Lacunar stroke (cont’d) Pure motor hemiplegia (lesion in posterior limb of internal capsule) – equal weakness of contralateral face, arm, end leg with dysarthria. Pure sensory stroke (lesion in VPLnucleus of thalamus) – numbness and tingling of contralateral face and limbs. Sensory examination may be normal! Dysarthria/clumsy hand (lesion in dorsal pons) – dysarthria due to weakness of ipsilateral face and tongue associated with clumsy but strong contralateral arm. Ataxic hemiparesis (lesion in ventral pons) – mild hemiparesis with more marked ipsilateral limb ataxia Severe dysarthria with facial weakness (lesion in anterior limb of internal capsule) – dysarthria, dysfagia and even mutism with mild facial and no limb weakness. Stroke - investigations CONFIRM THE DIAGNOSIS Computerised tomography (CT scan) 1. All patients should have a CT scan, urgently if conscious level depressed diagnosis uncertain on anticoagulants before commencing/resuming anthitrombotics if thrombolysis is considered Infarction is evident as a low density lesion which conforms to a vascular teritory. Subtle changes occur within 3 hours in some pts; most scans become abnormal within 48 hours. Early hypodensities Blurring grey/white matter distinction Dense artery sign Hyperdense thrombosed middle cerebral artery 16h 20min Lacunar stroke CT scan also identifies intracerebral haemorrhage or tumour Stroke – investigations (cont’d) CONFIRM THE DIAGNOSIS Magnetic resonance imaging T2 prolongation (hyperintensity in relation to white and grey matter) occurs within hours of onset of ischemic symptoms. Advanced technique, diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and perfusion imaging (PWI) show respectively early infarction (cytotoxic oedema) and ischaemic tissue at risk (‘ischaemic penumbra’). These advanced techniques are valuable predictors of outcome and guide treatments directed as thrombolysis. 1. Stroke – investigations (cont’d) 2. DEMONSTRATE THE SITE OF PRIMARY LESION a) Non-invasive investigation Ultrasound – Doppler/Duplex scanning: assesses extra- and intracranial vessels. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) A non invasive ultrasound technology used to evaluate blood flow velocity in the major basal intracranial arteries. Transcranial Color Coded Duplex (TCCD) TCCD sonography is a newer technique that permits the real-time visualization of the intracranial vascular anatomy and blood flow dynamics. Stroke – investigations (cont’d) 2. DEMONSTRATE THE SITE OF PRIMARY LESION a) Non-invasive investigation Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) – dynamic helical CT, following bolus injection of non-ionic contrast, can be used to investigate both intracranial and extracranial vasculature. CTA compared with DSA correctly classifies the degree of carotid stenosis in 96% of cases but is insensitive to ulcerative plaques. It is best used in conjunction with Doppler. CT angiography (CTA) Stroke – investigations (cont’d) 2. DEMONSTRATE THE SITE OF PRIMARY LESION a) Non-invasive investigation Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) – ‘Time of flight’ or contrast enhanced techniques are used. It tends to overestimate the severity of stenosis. When assessing the carotid arteries it is best used in combination with Doppler. Its non-invasive nature makes it helpful in investigating the intracranial circulation. MRA Stroke – investigations (cont’d) 2. DEMONSTRATE THE SITE OF PRIMARY LESION b) Digital intravenous subtraction angiography (DSA) Stroke – investigations (cont’d) 3. IDENTIFY FACTORS WHICH MAY INFLUENCE TREATMENT AND OUTCOME - General investigation Chest X-ray (cardiac enlargement, HT,…) ECG (cardiac disease) Blood glucose (diabetes) Serum lipids and cholesterol (hyperlipidemia) Full blood count (polycythaemia, thrombocytopenia) Urine analysis (polyarteritis, thrombocytopenia) Auto-antibodies Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) Note drug history (oral contraceptives, amphetamines,…) Selectively cardiac ultrasound, HIV screen, viscosity studies, anticardiolipin antibodies, … - - Cerebral infarction – management The acute stroke Treatment aims: 1/ prevent progression of present event 2/ prevent development of complication (e.g. aspiration pneumonia, pressure sores, deep vein thrombosis) 3/ to rehabilitate the patient 4/ prevent the development of subsequent event Ad 1/ Thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) TPA is approved for treatment of acute ischemic stroke. The key is delivery within 3 hours of stroke onset. This agent is associated with rapid recanalisation of occluded vessels. TPA is administered intravenously, randomised clinical trials of other thrombolytics as well as use of TPA after ‘3 hours window’ either i.v. or i.a., combination of TPA with mechanical recanalisation etc. are currently under way. General measures – hydratation, oxygenation, slow correction of blood pressure, treatment of oedema DB -- Mismatch 5:24 NIH 16 8 cc 71 cc 23 cc 5 cc M1 occlusion +4:23 +4:23hrs hrs NIH NIH14 14 Recanalization Cerebral infarction – management (cont’d) The acute stroke Ad 4/ Prevention of further stroke The recognition of risk factors and their correction to minimise the risk of further events forms a necessary and important step in long-term treatment. Control hypertension Emphasize the need to stop cigarette smoking Correct lipid abnormality Give platelet antiaggregation drugs (aspirin or in selected cases Clopidogrel) to reduce the rate of reinfarction Remove or treat embolic source (long-term anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation) Treat inflammatory or vascular inflammatory diseases Stop thrombogenic drugs, e.g. oral contraceptives.