ncarf

advertisement

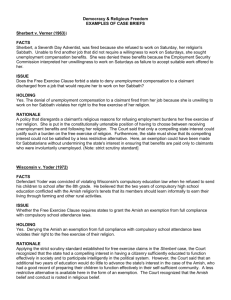

David Belton is a British documentary maker and the director of The Amish. As the project got underway, AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Executive Producer Mark Samels showed Belton an image of Amish children running through a field. Belton became fascinated by the story behind the photograph and what it revealed about the ways in which the U.S. Constitution remains such a vital document in American culture. Article by David Belton On a cold November morning in 1965, a journalist took a photograph that would inspire a religious freedom movement as well as a legal battle culminating in a historic Supreme Court decision. The grainy, black and white image of a group of Amish children running away from police into a cornfield in rural Iowa appeared in local and national magazines and newspapers throughout the United States. That photo prompted a young Lutheran pastor, Rev. William Lindholm, to begin a lifelong commitment to safeguard Amish religious freedom. Forty-five years after that picture was taken, I met Rev. Lindholm at his home near Detroit. He is in his 80s now but still preaches most weeks and remembers, with absolute clarity, the events of almost 50 years before. He told me that not long after he saw the photograph, he was in northern Michigan working at a Lutheran church camp and met several Amish men who were helping with its construction. They explained how they were being forced to send their children to school beyond the age that they felt was necessary for their way of life. Rev. Lindholm believed this infringed on the religious group’s constitutional rights. When he reported it to his superiors, they sat on their hands. Then when they suggested he do something about it himself, he set up the National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom. Within a year, he became aware of three Amish fathers in Wisconsin who were charged with violating the state’s compulsory school attendance law for refusing to allow their children to attend high school. Jonas Yoder, Wallace Miller and Adin Yutzy were like many other Amish in several states who had fought for more than 30 years against compulsory education beyond eighth grade. With some reluctance, they agreed to allow Rev. Lindholm to find a lawyer to defend them against the charges. The Amish rely on pacifist, nonlegalistic recourse to conflict, and their willingness to be represented in court in this case caused much consternation within the Amish community. Many Amish believed that they were better off negotiating with local authorities in matters such as school attendance rather than risking a judgment against them in a court of law. Rev. Lindholm still remembers walking into the Yoder family's kitchen, the initial reluctance of the three men to become a "test case," and their final, tacit agreement to allow Rev. Lindholm to use their case to try to change federal law and allow all Amish to pursue their faith free from government interference. Rev. Lindholm hired William Ball, a famous constitutional lawyer, to represent the Amish. They were convicted at trial and lost their first appeal in the Wisconsin Circuit Court. Ball appealed again to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, this time winning -- the convictions were overturned. As Rev. Lindholm recalled this victory, there was a mischievous gleam in his eyes. The State of Wisconsin appealed to the United States Supreme Court. It was precisely what Rev. Lindholm wanted -- a federal test case. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Amish in the 1972 decision Wisconsin v. Yoder (406 U.S. 205), enshrining the rights of all Amish to opt out of schooling after eighth grade. Amish and Old Order Mennonites remain the only religious groups to have been granted such an exemption. The National Committee for Amish Religious Freedom and Rev. Lindholm remain active to this day, fighting on behalf of Amish people. I asked Rev. Lindholm why he had decided to become so involved in the Amish. This is America, he told me. "The Amish are here because we allow them to have religious freedom. And that makes this country great, to allow people that are different to be here. We don’t require every single person to be like another person. We have freedom, and that’s why it’s a wonderful country." Then he looked shyly at me and added, "And when I was at college I won an oratory prize in defense of religious freedom, so I guess I didn't really have a choice."