Suggested Answer

advertisement

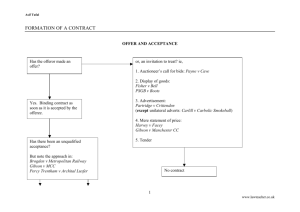

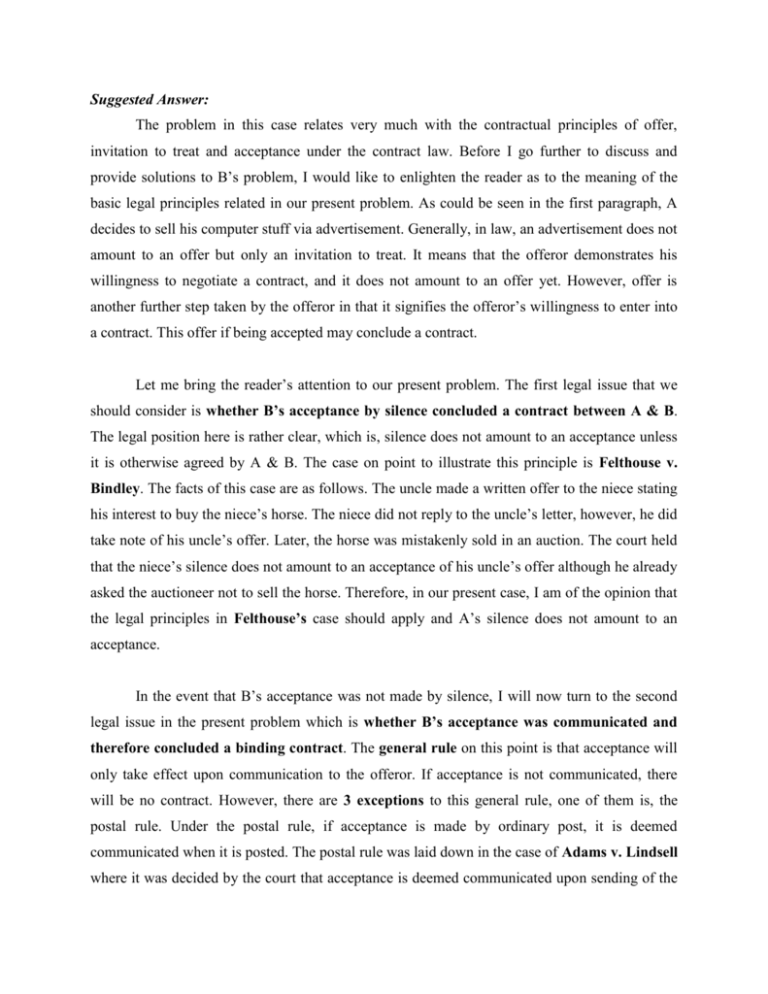

Suggested Answer: The problem in this case relates very much with the contractual principles of offer, invitation to treat and acceptance under the contract law. Before I go further to discuss and provide solutions to B’s problem, I would like to enlighten the reader as to the meaning of the basic legal principles related in our present problem. As could be seen in the first paragraph, A decides to sell his computer stuff via advertisement. Generally, in law, an advertisement does not amount to an offer but only an invitation to treat. It means that the offeror demonstrates his willingness to negotiate a contract, and it does not amount to an offer yet. However, offer is another further step taken by the offeror in that it signifies the offeror’s willingness to enter into a contract. This offer if being accepted may conclude a contract. Let me bring the reader’s attention to our present problem. The first legal issue that we should consider is whether B’s acceptance by silence concluded a contract between A & B. The legal position here is rather clear, which is, silence does not amount to an acceptance unless it is otherwise agreed by A & B. The case on point to illustrate this principle is Felthouse v. Bindley. The facts of this case are as follows. The uncle made a written offer to the niece stating his interest to buy the niece’s horse. The niece did not reply to the uncle’s letter, however, he did take note of his uncle’s offer. Later, the horse was mistakenly sold in an auction. The court held that the niece’s silence does not amount to an acceptance of his uncle’s offer although he already asked the auctioneer not to sell the horse. Therefore, in our present case, I am of the opinion that the legal principles in Felthouse’s case should apply and A’s silence does not amount to an acceptance. In the event that B’s acceptance was not made by silence, I will now turn to the second legal issue in the present problem which is whether B’s acceptance was communicated and therefore concluded a binding contract. The general rule on this point is that acceptance will only take effect upon communication to the offeror. If acceptance is not communicated, there will be no contract. However, there are 3 exceptions to this general rule, one of them is, the postal rule. Under the postal rule, if acceptance is made by ordinary post, it is deemed communicated when it is posted. The postal rule was laid down in the case of Adams v. Lindsell where it was decided by the court that acceptance is deemed communicated upon sending of the letter, not upon communication. (Explain the facts of Adams’ case). Before I come to my solution on this issue, I would like to bring the reader’s attention to the exceptions to the postal rule, which is instantaneous communication. If communication is made through an instant method, such as telephone, fax or telex, then postal rule shall not apply. The case of Entores could illustrate this exception to the general principle where it was held as such. (you can explain brief facts of Entores case). However, this exception does not apply here because B posted the letter on Wednesday evening, which was earlier than A’s withdrawal which was made on the Friday evening. Therefore, I am of the opinion that postal rule applies and acceptance should be deemed communicated upon sending of B’s letter. In a nutshell, when acceptance was communicated to A by the application of postal rule, a contract between A and B has been concluded. The act of A to have sold the computer to a third party has sufficiently breached the contract and this raises the right for A to sue B for breach of contract.